It’s a world away from where he was.

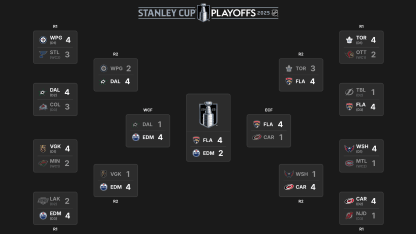

He had spent that six-month hiatus outdoors, mostly, fishing and working and being. He knew that he might be done with the game of hockey, the place where he had made his home his entire life, ever since he started playing, ever since he was handed the run of the Hartford Whalers at 28 years old by Jim Rutherford.

It could have been the end for him. He considered himself retired, something his dad had done at 54 after spending his days as an elementary school principal. Now, at 54, it might all be over for him, too.

He could manage that. He could manage the emotions and the unfulfilled dream, the goal he had been working toward for 24 years as a head coach in the National Hockey League, for his whole life, really. He could reason his way to acceptance.

But.

“One of the days at the lake, I get up, put my boots on and I probably spent 11 hours outside working and I loved it,” Maurice said. “Except I was still working and I’m thinking, if I’m going to be working, if this is what’s left for me, you get up and you do stuff all day, might as well be hockey. So that’s kind of how it found me more than I found it.”

Few people are more precise with their language, more nuanced in their takes than Maurice. He often stops himself in the middle of sentences, press conferences, wanting to convey exactly his thoughts, with no misunderstandings, no room for misinterpretation.

He is particularly attuned to how his affection -- his appreciation -- for this team, this group of Panthers players reflects on those who have come before. They have been life-changing, he has said. But, at the same time, that doesn’t negate his Jets team and Jets players, or the Carolina Hurricanes or Toronto Maple Leafs or Whalers.

It is an important distinction to him, to the respect he has for them.

It’s noticed.

“He keeps things light, but he expects us to work our hardest and [he’s] very prepared and can get you up for a Tuesday night game against Columbus or whatever in the middle of the year, feels like a playoff game,” forward Matthew Tkachuk said. “His speeches and his ability to get us to run through a wall each and every game is a big gift.

“But he gets the buy in from the players and he treats all of us the same, which I think is really important as a coach, not to treat guys differently. He expects us all to work hard and treat each other with respect and everything, but he treats us all the exact same.”

It’s also the reason for the stops and starts, the rethinking of words, the careful crafting of what could otherwise be a throwaway line.

“He knows the game very well,” goalie Sergei Bobrovsky said. “He knows the human mind very well. He knows what to say and when to say [it]. He’s a big leader and he’s a big reason why we have three finals in a row.”

When it all ended in Winnipeg – or, to be precise, when Maurice ended it – he was exhausted, worn out. Burnout had crept in and, as he put it, “by the of it, I wasn’t any good at my job and I didn’t feel like I was effective.”

The mental stress was negatively impacting his life and, simply put, it was time.

But while the feelings were similar to when he was fired the first time with the Hurricanes, in 2003-04, after eight seasons, there were differences.

“I gave what I had to give in Carolina and I was fine with it. I was good with what I had done,” Maurice said. “I gave what I had to give in Winnipeg, but I was not fine with it. I was not good with where I’d gotten to. That’s the best way to sum it up.”

And that’s where he believed he would leave it. With the lawns always mowed and the grass always manicured and his days spent outside, with the disappointment that he couldn’t have been better for Winnipeg, a place that he holds dear, and where his daughter still lives.

Life, as he said, was perfect. He wasn’t in need of a return to hockey.

He was at pea—.

He was managing.

Maurice really wants to get his point across. He really wants to explain his career, how years of striving and working and hoping and falling short can be put into the context of now, of having won, of having reached a goal he had let go of attaining, a dream he had accepted would remain just beyond his fingertips.

“A little bit like this,” Maurice begins. “Let’s say you go to the casino and it’s pretty good. Like, sometimes you get to the final table, but not very often, it’s hard to get to that final table. Sometimes, you don’t even get invited to the tournaments, but you’re a professional poker player and you stack up 20 years.

“And then in the 21st year, you hit the jackpot and everybody is berserk and it is unbelievable, you just won $10 million dollars and it’s awesome. And you know that’s true, but you lost [$500,000] every year for 20 years so -- this is exactly how I feel -- everybody around you thinks it’s awesome. You do too. It’s good.

“But when you walk out of the casino, I broke even. It’s a really peaceful breaking even. That’s exactly how it feels.”

So what if it all ended today? Or if it all ended after this Stanley Cup Final, win or lose, would he be at peace?

“Yeah,” Maurice said. “One hundred percent. I would be at peace now. I’m still one under .500 in the Final. But I’d be -- I’d be at peace. … I think prior to this, I could manage my career mentally and be OK with it. I had some pretty good ups, I had some really big downs. And I broke even. I’m at peace. One hundred percent.”