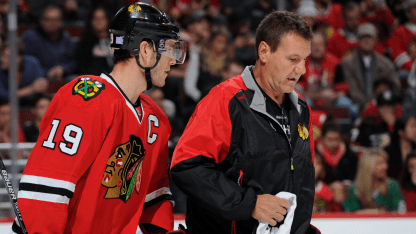

The Blackhawks have an elite medical staff and a mental skills coach. Even when the organization wasn't quite as organized as it is now, a continuity evolved with the inner sanctum.

Jeff Thomas

, assistant athletic trainer, is in his 17th season.

Troy Parchman

, the head equipment manager, his 25th.

Pawel Prylinski

, massage therapist, his 28th.

Dr. Michael Terry

, the head team physician, his 15th. They've seen it all, heard it all, and are among the first to learn of pending roster adjustments, not that they impart information with the outside world.

Gapski in many ways is the glue. It can be complicated if a common mission is not shared - what's best for the individual and the Blackhawks - but the fact that he has survived so many regimes confirms Gapski's status as indispensable. If you want to stump him, as how many general managers and coaches with whom he has worked. Law of averages dictates that one of them would have chosen "his guy" to be head trainer.

Gapski's break occurred during the summer of 1987, much to his surprise.

"Bob Murdoch was hired as coach here," recalls Gapski. "I was head trainer at UIC, where I went to college. I'm not sure exactly why, but he contacted me about coming to the Blackhawks. I was a big fan. Saturday nights as a kid, their games on TV were a ritual. My mom, Marlene, would make a big bowl of popcorn. We'd watch with my dad, Mike. I'd look for the trainers behind the bench, Skip Thayer and Lou Varga, but had no aspirations about going pro. When Bob offered me the job, my parents were through the roof excited."

While at UIC, Gapski switched majors to applied sports nutrition. In those days, the Blackhawks' version of same comprised "a bucket of water, a bucket of Gatorade and some power bars." The rest of the NHL operated similarly. Although Gapski proudly considers himself old-school, he was way ahead of the curve that now pervades all sports: you are what you eat and hold the mayo. The Blackhawks have replaced those buckets with their own chef.

"You don't put regular gas in a Mercedes," reasons Gapski. "Why put garbage food into a professional athlete? It's much different now. We travel with our own doctor, which is huge. We have Julie Burns, an expert on proper diet. The support we have from [Chairman] Rocky Wirtz and [President & CEO] John McDonough the front office is the best ever since I've been here. A great new practice facility. The reception to new ideas.

"Everything is so advanced now, like with the league-mandated concussion protocol. You don't want to stay stagnant. One thing that hasn't changed is the players. They're making big money now, but they're still real, genuine, down to earth. Ask anyone who's been around all sports. Hockey players always top the list."