It is always advisable for a young man entering the National Hockey League to exercise humility. But Jeremy Roenick, whose physique was a cross between a thermometer and a 2-iron, took bashful to an extreme when he first showed up with the Blackhawks in 1988.

"I was afraid to take my shirt off," he recalled. "I was 158 pounds. Before the draft that summer, my agent, Neil Abbott, told me never to appear in public with my shirt off because he didn't want teams to see how skinny I was.

"Well, after Chicago took me, I was still skinny and I saw all these big guys around me in camp like Dave Manson and Al Secord and Dan Vincelette who were ripped. You know how locker rooms are. Guys walk around naked. Not me. I would go into the bathroom stall to dress and undress. I looked like a marathon runner. The coach, Mike Keenan, gave me these football pads to wear under my jersey so I'd appear bigger."

THE VERDICT: Roenick's draft memories

Team Historian Bob Verdi writes about Jeremy Roenick, who the team selected eighth overall in 1988

Soon, Roenick's body filled out and his body of work exploded. In a relatively brief but meteoric career over eight seasons with the Blackhawks, he scored 267 goals - still ninth on the all-time franchise list - before moving on to amass a career haul of 513, plus 53 in playoffs. Upon selecting Roenick eighth overall in the 1988 draft, the Blackhawks weren't exactly sure what they had besides a promising teenager who could have used a few milkshakes.

When the Blackhawks pick No. 8 again in Dallas on June 22, they should only be as fortunate as they were three decades ago in Montreal. Roenick became a prolific sniper in Chicago and at four other NHL teams. Moreover, he immediately declared himself to be, as Bobby Hull will say about a precious few lodge brothers, "tougher than a night in jail."

Roenick's reputation was cast in enamel and early. During a playoff game at St. Louis in his rookie year, Glen Featherstone of the Blues imbedded the shaft of his stick into Roenick's mouth. Though stunned, he gathered four dislodged teeth and showed them to Referee Kerry Fraser. Featherstone was banished for five minutes, and the energized Blackhawks tallied twice in eight seconds. Roenick later scored the winner, eliminating the Blues. The Blackhawks' 4-2 conquest was instantly 'crowned' as "The Chiclets Game." Keenan lauded Roenick, who enjoyed a buoyant debut to postseason hockey.

"Before all that, in the same game, I took a skate blade to the nose and needed eight stitches," Roenick said. "First stitches ever for me. Maybe that night helped me gain a little respect with my teammates and around the league. I know Keenan was happy, and that didn't happen every day."

As the '88 draft approached, Roenick was generally ranked to be among the best ten or 12 prospects. However, he had just completed only his junior year at Thayer Academy. Another red flag: Thayer Academy was located in his native Massachusetts. Eight years prior, a bunch of American college kids had authored the Winter Olympics "Miracle on Ice" against a machine from the Soviet Union, but reservations persisted about that path to the NHL.

"Lake Placid helped, but the best option was still viewed as going through the junior ranks in Canada," Roenick said. "Bob Pulford, Chicago's general manager, was part of the old school, which was fine. But I was told that Jack Davison, the Blackhawks' head scout, pretty much put his job on the line for them to pick me if I was available.

"Quebec had the third and fifth picks, so I thought there was a chance I'd go to the Nordiques. Then there was a rumor about the Blackhawks exchanging spots with Buffalo, so the Sabres could move up to eight. That never materialized, and the Blackhawks wound up selecting me."

But not before, during pre-draft machinations, members of the Blackhawks' front office requested that Roenick and his sunken chest step on a scale. He refused.

"Did you ever see a scale score a goal?" barked Roenick, providing an early clue to JR's typical New England bluntness.

During the summer, Roenick took courses to complete his high school education while Abbott talked salary with the Blackhawks. When negotiations stalled, Roenick baffled everybody, including Abbott, by deciding to enroll at Boston College. No hockey scholarships were available, so Roenick was offered one in football. He could play his primary sport and also be a place kicker. No problem, said Roenick. He'd done that at Thayer. Alas, his college experience was over before it was over.

"My first day in class, the professor handed out this 'syllabus' of about 80 pages," Roenick recalled. "I didn't know what a 'syllabus' was. Never heard the word. I asked a girl next to me what it meant and she said it was an outline for the course. I got up, went to a pay phone, called Neil and told him to get a deal with the Blackhawks. No 'syllabus' for me. It was basically the same money we'd turned down all summer, but that was before my syllabus shock."

Roenick agreed to terms, and was off to Chicago. After signing at the Stadium, he and Abbott looked for a taxi. Good luck.

"Rough area in those days," Roenick said. "Here's two guys in suits, carrying a check for $50,000. Neil finally had to jump in front of a CTA bus on West Madison Street. He gave the driver $100 to take us to the hotel, and another $100 to a passenger for the detour."

In an early exhibition game, Roenick played as he played in high school. Speed, skill, not much contact. If he was bumped at Thayer, he might collapse "like a soccer player," seeking sympathy or a power play. But when he failed to finish a check in that preseason affair, Keenan grabbed him by the neck. Be physical in the NHL, or be gone. The message stuck. Roenick learned to thrive on hitting and being hit.

After three regular-season games, Roenick was sent for seasoning to the Hull Olympiques, a team owned by Wayne Gretzky in the Quebec Junior League. Roenick stormed with 70 points in 28 games. Come February, the Blackhawks were beset by injuries. Roenick was recalled, he hurried to Minnesota, and scored his first NHL goal against the North Stars. As an emergency replacement, Roenick bore sweater No. 51 without further identification.

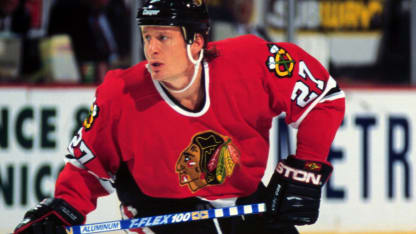

But he made a name thereafter, famously wearing No. 27, accumulating 53 goals in 1991-92 and 50 more the next season while evolving into one of the most popular Blackhawks ever. For the record, Roenick registered the last Blackhawks goal in the Stadium: April 24, 1994, against the Toronto Maple Leafs in Game 4 of the Conference Quarterfinals. His overtime score - in addition to assisting on the first three goals - produced a 4-3 victory and a 2-2 tie in the best-of-seven series. The Blackhawks played Game 6 at the Stadium four nights later, lost 1-0 and were ousted, four games to two. Next stop: United Center.

"I wish I could have played my whole career in Chicago, but it wasn't to be," reflected Roenick. "It's an amazing city with great fans, and I met a lot of tremendous guys: Doug Wilson, Steve Larmer, Keith Brown, Steve Thomas, Troy Murray, Michel Goulet. They took a skinny and quiet American under their wing. And after a while, I wasn't so skinny anymore."

Or as quiet. Talk about typecasting. "JR" has become a colorful TV analyst. When the Blackhawks won the 2010 Stanley Cup, he shed a few tears on camera.