This story was originally written by Post-Gazette Sports Editor Roy McHugh and was published on April 14, 1971.

It can't be acquired; they have it or they don't, the quality that sets apart the exciting performer.

By one definition, it's chemistry - exactly the right mixture of talent, style and competitive spirit. Quoting the same authority:

"Some players make it strictly because of their competence… and then there's the player who is both competent and competitive but has a little something extra. He has style. He does what he does with a special flair, a special éclat. He is colorful. There is something of the showman about him. He is the type of guy who draws standing-room-only crowds because they know he will make things hum."

Historical Headlines - Briere's Magic

By

Roy McHugh / Pittsburgh Press Sports Editor

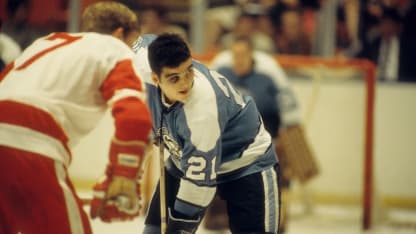

Michel Briere was such an athlete. Red Kelly first saw Briere at the Penguins' training camp in September of 1969. "He was showing me moves you can't put into a hockey player," said the coach.

Briere skated easily. He skimmed across the ice like a waterbug, not with great speed but with a phantom elusiveness, deftly avoiding body checks, probing and questing for the puck. His shot was quick rather than powerful, coming invariably when the goalkeeper least expected it, preceded as likely as not by a feint, by a dip of the shoulder.

'A Little Boy'

"When he picked up that puck, you knew things could happen," said Kelly last night. "You felt he could take it all the way down, that the puck would end up in the other guys' net." The feeling was a reaction to the chemistry of Briere, to the promise he communicated, for in his only year with the Penguins he scored just 12 goals.

Yet the spectators sensed his possibilities. They believed he would make things hum. Part of his appeal was the way he looked. Slight and dark, with flared nostrils, on the ice Briere called to mind a fugitive fleeing from hunters. While he lay unconscious in a Montreal hospital last summer, his teammate, Jean Pronovost, said, "He looked like a kid, he looked like a little boy, and he was out there doing great things."

At the start of the season, Kelly tried to protect Briere, keeping him out of matchups with stronger, more experienced centers. On faceoffs it seemed that Montreal's Jean Beliveau beat him to the draw every time - at the start of the season. By the end of the season, Briere was beating Beliveau, getting his stick on the puck before it hit the ice.

The heavies in the league, taking him for a pipsqueak, were impatient to lean on Briere. They would chase him right out of the rink, they told themselves with a smirk, but when the moment came to lean, they'd be leaning, quite often, against nothing. Briere would have slithered away.

In Philadelphia one night, two Flyers took a run at him, collided head-on, and knocked each other out.

The Giant-Killer

Scotty Bowman, the coach of the St. Louis Blues, made it a point last year during the Stanley Cup playoffs to harass Briere with Noel Picard and Bob Plager, his burliest defensemen. From Kelly no counter measures proceeded. "There he is - there's my little baby," Kelly said. A common sight during the playoff series was Kelly's little baby skating toward the goal while the St. Louis bad boys sprawled on the ice in his wake.

"If they looked at the puck, he'd be gone," said Kelly. "He was slippery, he could shift and make movements, but all the time he was doing this he was skill skating. A lot of guys, when they shift, aren't going anywhere. Mike kept on skating at the same rate of speed."

Now he is dead at age 21. On trips to Montreal last season, Kelly would visit Briere. "It made you feel kind of bad," Kelly said. "You'd walk in and sit down, you'd take hold of his hand. He'd turn his head toward you and his eyes would open, staring. He couldn't talk. I was always optimistic, but the last time I saw him…"

Michel Briere had been only clinically alive since the night 11 months ago when his burnt-orange sports car missed a curve on a road in upper Quebec. Yesterday that life departed. A particular magic blend of talent, style and competitive spirit is gone.