October is Dwarfism Awareness Month - please visit Little People of America's website to learn more.

BOSTON - Marty and Sue Myers left the doctor's office with plenty to process.

They had just been told that their unborn son was going to have to live with achondroplasia, a form of dwarfism, and that he was never going to be able to drive a car or play a team sport. Going to college or finding a career would be improbable.

The list of limitations that was being put before them was endless.

On Journey to the NHL, Mat Myers Has Defied the Odds

Bruins video coordinator, born with dwarfism, has made it to the top with perseverance and conviction

© Michael Penhollow/Boston Bruins

By

Eric Russo

BostonBruins.com

"The doctor let us [into his office] and he opened up a book and he said, 'This is what your son is going to look like,' and he showed us a picture of a dwarf," Marty Myers said as he remembered back to that meeting some 31 years ago. "My wife and I were like, 'what does that mean?' We were just shocked. We didn't know anything about dwarfism, didn't know how it got into our genes, how we passed it on to our son. We didn't know anything."

But when the Myers got home, they realized they did know one thing for certain: they were going to do their very best to never tell their son he couldn't do something.

"We digested it and we talked," said Marty Myers. "We said, 'You know what? We're just going to do what we planned on doing from the start. We're going to raise him the best we can, we're going to expose him to everything that he wants to expose himself to. We'll hopefully never have to say no.' That was our goal to never have to say no."

Not long after that conversation, Mat Myers was born.

And so, too, was a story filled with inspiration, perseverance, and conviction - a journey that has led a kid from Manchester, New Hampshire, counted out before he was even born, to the National Hockey League and the coaching staff of his hometown Boston Bruins.

-----------------------

Mat Myers learned how to skate before he learned to walk.

When he was a toddler, Myers' legs were bowed and his head was a bit larger than normal, which made it difficult for him to find his balance and led to visits to an occupational therapist in an effort to find solutions.

Marty Myers, who grew up playing hockey and had just begun coaching shortly before his son was born, had an idea. Even though Mat was only 2 years old, it was time to get him on the ice.

"My dad had found a pair of skates," said Mat Myers, now 31. "It had two blades on it, and we ended up going to a pond and had a milk crate and I actually learned how to skate a little bit, pushing around the milk crate, before I ever learned how to walk."

Mat Myers had already found his calling - and his confidence.

"I'm able to do this. And this is pretty hard," Myers recalled. "The average person can't just pick up skates and be able to skate. It kind of helped shape my mindset that I can sort of do anything else.

"Hockey's been my life and I think the biggest connection with it is because it's really given me my confidence - both in the rink and outside the rink. It makes me feel at my best."

From there, Myers' parents began to outfit him in hockey gear. But not just on the ice.

"My parents bought me a big Cooper bucket [helmet] and some elbow pads and they would put that on me," said Myers. "I loved just wearing the equipment. But little did I know, they were putting that on me so when I ran around the house and I tripped and fell, I wouldn't get hurt. I'd be running around the house in the equipment, and absolutely loved it."

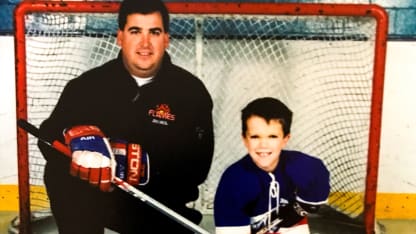

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

It helped that Myers' younger brother Mackenzie, two years his junior, picked up the game and began playing for the Manchester Flames youth hockey organization, for whom their father Marty was a coach.

"I found myself always going to his practices and watching," said Mat Myers.

And after a while, Myers began to wonder why he wasn't out on the ice with his brother.

"Mat said, 'Why can't I play?' We said, 'You know what? If you want to play, you can play.' We never told him no," said Marty Myers.

Despite the challenges of finding equipment that fit properly, Myers ended up playing for several years, beginning when he was seven or eight, with his brother Mackenzie by his side.

"It took a little bit [longer] because finding equipment was a little bit tougher," said Myers. "I had soccer shin guards, I had pants that were kind of caught up, and a stick that was way too big."

But when Myers turned 12, his father had to deliver him some crushing news. Marty Myers could no longer justify putting his son on the ice as the physicality of the game started to become more of a risk.

"My dad had the conversation with me that it would be my last season, that I'd have to quit due to checking being involved," said Myers. "He didn't want me to get hurt. It kind of crushed me."

It was an equally crushing conversation for Marty Myers, who was going against his vow to never tell his son he couldn't do something.

"We never told Mat no until it became unsafe," he said. "When it became unsafe, as a parent we've got to protect your safety so we've got to tell you no, but let's be creative and see what we can do to continue what you love to do…we'll never tell you that you can't try something new.

"But we'll always have to be realistic and make sure that whatever you do is safe for you and the people that are around you. In fairness to the people that he was playing against, we want them to compete, we don't want them to hold back."

It was then that the next chapter in Mat Myers' hockey journey began to take shape.

-----------------------

While he could no longer pursue the sport he loved on the ice, he was eager to find ways to stay involved. It started with running the scoreboard at his brothers' games and eventually turned into him operating the clock for pretty much every game that was being played at the local rink.

"I ended up dropping Mat off at the rink at 5 o'clock in the morning and picking him up at 3, 4 o'clock in the afternoon because he just wanted to be a part of it," said Marty Myers.

The scoreboard, however, wasn't quite enough. Myers began to keep detailed notes of what he was seeing on the ice, writing down strategic commentary and critiques for each player - including his own brothers, Mackenzie and Mitchel.

As Myers put it, he was living vicariously through them.

"I would go to the rink and envision what it was like if I kept playing. My brothers, I thought, were very good, so I would think, 'That would be me out there, I would be doing this,'" said Myers, who eventually became the student manager for the hockey team at his own Trinity High School, where he was able to join the squad on the ice from time to time for practices.

"After a game, instead of my dad coaching them up and giving them the X's and O's, I would come in with the criticism on the car rides home. It was kind of cool and unique how we bonded as a family. That's how I grew close to my brothers.

"If there were snow days, we would have the ice all to ourselves and we would run plays - and the same with me being the one in the garage shooting pucks. That sort of inspired my brothers to shoot more pucks."

Quite simply, hockey was the glue that kept the Myers family together.

"We always knew we'd find each other at a rink," said Myers. "We'd be pulled in so many different directions, but we knew at some point during the day, we would all see each other as a family at a hockey rink and then the car ride home. We'd decompress in that sense. I was my brothers' biggest fan growing up."

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

Marty Myers, meanwhile, moved on from the Manchester Flames organization to coach the Bedford High School (N.H.) boys' hockey team, where he was at the helm from 2009-20, amassing a 200-51-6 record, nine playoff appearances, eight trips to the state title game, and six state championships.

The chance to be around a team - a highly successful one at that - even if it meant not being a contributor on the ice, was an opportunity that that turned out to be invaluable.

"My dad was a very successful coach growing up…I always admired him in the sense that he taught me a lot of how to be a good person and a good teammate through the way he coached his teams, "said Myers. "He brought me around the locker room, and I got to observe, and I really appreciated that growing up."

It was that extended time around his father's teams that allowed Myers to observe the innerworkings of a hockey club, how a culture was built, how camaraderie could lead to success, and how different perspectives could lead to creativity.

"I was seeing things," said Myers, "that maybe the average player wouldn't see, so that helped me learn the game."

And it's what left him wanting more as he made his way to college.

-----------------------

When Mat Myers began his college career at the University of New Hampshire in the fall of 2013, he was determined to be a part of the hockey program in any fashion he could. So, when he arrived at the Durham, New Hampshire, campus, Myers immediately called men's hockey coach Dick Umile in hopes of securing of a role with the team.

Unfortunately, Umile told Myers, his staff was full with four student managers already working for the club. But he encouraged Myers to stay in touch.

Myers did much more than that. Every day before he headed to the library to study for his Communications classes, he would show up at Whittemore Center Arena to watch practice and get familiar with the team. Umile noticed him sitting in the stands and, eventually, called him down and told him whenever he was at the rink to watch practice, he could do so from the bench.

"This kid is unbelievable," Umile recalled thinking after meeting Myers. "He may be a little guy but he's like 7-feet tall. He just walked in here like he owned the place, and he knew everything about it."

Later that year, Myers was named a student manager.

"Obviously, it was the best thing we ever did," Umile said of brining Myers onboard. "From Day 1, he just presented himself with confidence and he became, personally, a good friend of mine and someone who I respected for all of those reasons."

Umile recalled one particular moment before a game at Boston University that represented everything that Myers meant to his team.

"I remember down at BU him giving a pregame speech that was absolutely phenomenal," said Umile. "They put him up on a box so he could get up and talk to our team. He was tremendous. He just had the total respect of our team and everybody involved."

In addition to becoming the team's student manager, Myers also took on video coordinator duties alongside Sean Andrake - who is now his assistant with the Bruins - and helped transform the way the team analyzed its games.

"Just being positive and working hard and not letting anything hold you back," Andrake said of Myers' mentality both then and now. "He's always had to overcome stuff, but he's done it…he came in [to UNH] and…typically your first year, you're a part of a group but you're eased in, right?

"But he came in, he made a funny joke, and from that point on, that was his moment of, 'All right, now you're here with the team.'"

© Zachary Concannon/Boston Bruins

No, Mat Myers was not suiting up for the Wildcats. But his knowledge and passion for the game was as powerful as the players on the ice - and that was exactly the kind of person that Umile wanted around his club.

"All you have to do is look at what he's accomplished," said Umile. "It's not an easy pass to get to the level that he's at with dwarfism…I'm just so proud of him.

"Maty Myers had a dream and he made it happen. I admire him - and he's my hero."

-----------------------

As Myers' time at UNH came to a close, his goal was to continue his hockey career, so he began applying for both team services and video jobs, mostly at the American Hockey League level. But nobody came calling.

"I wasn't hearing back from any teams," said Myers. "Graduation time came, and it was like, 'Oh shoot, all my friends have jobs, hockey might not be it this first year.'"

Myers reluctantly put his hockey ambitions on pause and accepted a temporary job as a communications consultant with one of the largest energy companies in New Hampshire.

But only a few months later, his hockey journey resumed when USA Hockey called and asked Myers to assist them as they implemented new video software, XOS Digital, the same program that he was using at UNH.

That opened the door for Myers to join the United States Women's National Team Program, which was based out of Bedford, Massachusetts, in the lead-up to the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Myers ended up winning three gold medals with Team USA over the course of two years with the program, including at the 2015 IIHF Women's World Championship in Sweden.

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

In the meantime, Myers was still aiming for the mecca. Making it to the National Hockey League remained the ultimate goal. As such, Myers reached out to the video coaches of three teams: Boston, Los Angeles, and Nashville.

"Boston because it was my hometown team," Myers explained, "the video coach in L.A. because I just thought L.A. was cool - it was the Manchester Monarchs' team, which was my hometown. And then the Nashville Predators because Nashville was always on my bucket list for a city to visit."

Initially, Myers did not hear back. But eventually a reply came that changed everything.

After connecting with Myers through social media, Nashville video coach Lawrence Feloney began to follow Myers' journey and his Twitter account called the Little Motivator, which was created to deliver short but impactful messages of inspiration and hope.

Feloney kept tabs on Myers and heard nothing but positive feedback from several people around the sport, including former Bruins video coach Brant Berglund, who had gone on to work for XOS Digital and had known Myers from his time using the software at UNH.

And when the Predators' amateur video coordinator position opened up in the summer of 2015, Feloney knew he had the perfect candidate. The position - which was vacated when Massachusetts native J.P. Buckley departed the Predators to become the Bruins' video coach - was essentially a video scouting role that worked with the Predators' amateur staff to help in the development of the organization's young prospects.

"His name just jumped out," said Feloney.

Myers' father, Marty, however, was admittedly not sold on the situation.

"Mat called me up and said, 'Dad, I want to go out lunch,' I was like, 'When does my son ask me to go out to lunch?'" Marty Myers recalled with a chuckle.

It was during that lunch that Mat told his father of the opportunity he had in front of him in Nashville. As parents do, Marty Myers expressed his concerns about leaving behind a stable job in his home state for a less secure position in a city he had never been.

"He walked away disappointed," said Marty Myers. "As did I."

Maty, though, has a special way of proving people wrong.

A few months after their initial conversation, Maty visited his parents' home and this time he wasn't asking for advice. He had already made his decision.

"He sat down in the living room and said, 'I'm going to Nashville,'" Marty Myers recalled. "Full disclosure, I had mixed emotions over it. But I told him, if this is what you want to do, this is going to be your thing and I'll help you any way I can.

"We loaded up his Toyota Corolla and drove overnight and he moved into an apartment in Nashville and started writing that part of his story."

Myers was in the amateur video role for one season before being bumped up to the No. 2 video spot at the start of the 2016-17 season. In his new position, Myers traveled with the team and worked closely with the players and Peter Laviolette's coaching staff during a magical run that ended in a loss to the Pittsburgh Penguins in the Stanley Cup Final.

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

"It was an easy decision to promote Maty to be my assistant," said Feloney. "He's got an unbelievable attitude and outlook on life…the kid's had to grind his whole life and work hard at things…he's just always had to overcome obstacles. That's a big part of why he works as hard as he does.

"His work ethic stood out…he was very good with the technical side of our job and the understanding of the software and computers and IT stuff. And then also understanding how coaches work and how coaches think. His hockey background and his hockey knowledge is different than a lot of people because his playing career was cut short."

Upon his arrival to the NHL, Myers was embraced - and respected - immediately.

"It was neat. It was really surprising…the people at this level - they're not only the best in the world at what they do on the ice, but these are quality humans off the ice, too," said Myers. "I've never, ever had an issue once in a locker room here at the NHL level of there being any form of disrespect, joking, mockery, anything of that sort. Everyone's been completely respectful.

"And it's been a little bit of a two-way street, too. I think it's pretty clear early on that they know that I'm not a former player, but once we have a few conversations, they see the hockey knowledge that I'm able to talk and insight I'm able to provide that it's really kind of cool the respect that's been given immediately.

"I'm very, very lucky because it is a very nerve-racking thing because I haven't played…you have questions going into every camp and into every organization. Your insecurities can creep in. As long as you stay confident in it, you build those relationships and the rest falls into line."

Myers made such an impression on the Predators' coaching staff that when assistant Phil Housley left to become the head coach in Buffalo following Nashville's trip to the Stanley Cup Final, he brought Myers along with him to become the lead video coach for the Sabres.

"It's not surprising to see him having success," said Feloney. "It's been special to watch and fun to watch because I don't think there's a person that's met Maty that isn't in his corner rooting for him just because of his personality and because of the energy that surrounds him. He's one of those people that's easy to cheer for in the game. He really is."

Myers went on to spend two years on Housley's staff with the Sabres before the biggest break of them all came in the summer of 2019.

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

-----------------------

On the heels of the Bruins' loss to the St. Louis Blues in the Stanley Cup Final, the club was looking for a new video coach to take the spot of J.P. Buckley, who was departing the organization for a new career. Buckley, who was at Boston University while Myers was at UNH, let his old friend know that the job was available, and he should throw his hat into the ring.

Myers, of course, jumped at the chance to join Bruce Cassidy's staff. As a kid who grew up just an hour away from TD Garden, an opportunity to work for the Black & Gold was too good to pass up.

Bruins general manager Don Sweeney felt the same after interviewing Myers.

"I think the three primary things for Maty were his energy, his love for the Boston Bruins being a New England guy, and his passion and knowledge for the game," said Sweeney. "Those things really, really resonated loudly, not just with Maty and interviewing him and spending time with him, but everybody that has worked with him and been around him.

"He's just an all-in guy and wants to be really good at his craft…he was clear cut the best candidate."

Some four years after leaving Manchester in his Toyota Corolla, Myers was heading home.

"It's a dream. I don't know how else to say it. It's a dream," said Myers. "The guys like Ray Bourque, Zdeno Chara, Patrice Bergeron, Brad Marchand - I'm still young enough where I watched them play. I was rooting for them before I ever received an NHL job in Nashville. I looked up to them and followed them as hockey players growing up. And meeting them for the first time, I was really starstruck."

And like he was in Nashville and Buffalo, Myers was immediately accepted and embraced within the Black & Gold's dressing room, while becoming an important piece of the Bruins family.

"The first time I see Chara, the first thing he says is, 'we're going to wrestle.' It breaks the ice and makes everything comfortable," said Myers. "Bergy, the respect that he gives on the day to day of asking about your personal life and getting to know you and every aspect, it makes you feel comfortable, it makes you feel like you're at home.

"It's really neat to see and you get to wear the colors and represent the team you grew up with. You take great pride in it, and it gives you an extra push to work so much harder on it. You're just overwhelmed with the pride that comes with it."

Marty Myers couldn't agree more.

"It's absolutely amazing. There is a piece of me where I say it's not surprising. And I mean that humbly," he said. "It's amazing to have a job with the Black & Gold in Boston…to play or work for an organization like that, to me, is a little boy's fairytale. Every hockey player from New England would want to play for the Boston Bruins, or want to work for, or have a piece of, or be a part of that type of organization.

"When people say to me, 'tell me about your kids,' Mat being my oldest, I start with him, and I just get blown away with where he's working and what he's doing and the people that he meets and the travel that he does. But I say, humbly, it's not surprising."

As the Bruins' lead video coach, Myers oversees the logging of every second of every game that the Black & Gold play so that the rest of the coaching staff and all the players have as much visual data as they need to better themselves throughout the season. Myers - along with his assistant Sean Andrake - also prepares video of opponents for pre-scouts and is the one radioing to the bench when coach Jim Montgomery is deciding whether to challenge for offside or goalie interference.

"I think his personality is infectious. His energy, his work ethic, I think that's what players would hope for in all the guys they have a chance to work with," said Sweeney. "Hopefully they're making their own games better because they're providing more knowledge - and then the coaching staff, how he works with the coaching staff, to make sure that their jobs are easier in some regards."

Myers often goes above and beyond, sometimes into the overnight hours, sending Bergeron and other players all their shifts after a game.

"I think he's amazing at his job. He's a hard worker, too," said Bergeron. "Sometimes after games, even at midnight, I'll get a text from him with my shifts broken down where I can actually watch them. I think it's the little details that make a big difference. Sometimes we talk about the team and the players and there's a lot of unsung heroes.

"He's definitely one of the people that goes above and beyond to make sure that we can go about our business. He's really helpful with what he does and helps us and the coaching staff to be at our best.

"He's been embraced, been part of the group, part of the family. His energy - he always has a smile, always cracking jokes. I think he's embraced by the whole team. We all love him."

© Zachary Concannon/Boston Bruins

And at just 31 years old, Myers, who earlier this month marked his 500th NHL game, is really just beginning his journey. Despite being involved in the game in some fashion for nearly three decades, those that know him believe there is plenty left for Myers to accomplish.

"I think he sets a great example for other people or other kids that are growing up and are looking for role models," said Feloney. "To me, that's exactly what he is. He's maximizing his potential and doing things that I'm sure people out there that are narrow-minded…would say, 'you can't do this, you can't do that.' He's proven that you can do this as a little person, and not just do it but excel at it.

"He's right where he belongs in Boston, working for the team he grew up cheering for and going to games at. It's the perfect fit for him. I think there's still probably even more growth for him, like where does it go from here?…I think the sky's the limit for the kid."

Both in the hockey world and in life.

-----------------------

Myers knows that every time he walks into a room, or out to the Bruins bench to watch warmups, or into the grocery store, or down the street, there are people who do a double take. They ask questions, they stare, they point, they take pictures, and sometimes they even make quips at his expense.

Unfortunately, it is nothing new. Myers has been dealing with it for all his life.

"I early on sort of figured out, growing up in the world of social media, that people will take pictures of me, that I sort of had to act certain ways or be aware of it," said Myers. "People will take pictures without my permission and try to discredit me or disrespect me."

During those moments, Myers thinks back to what his parents taught him, and one particular piece of advice that his father delivered to him as a child.

"Confidence for me has been something that my parents have always taught me. They tried to put me in good environments," said Myers. "My dad gave me some advice early on - the analogy he used was, 'Mat, when you're older, no one's going to hire you to dig a hole, they're going to hire you to think of ways to dig that hole and make it the best hole that's ever been dug.'

"I've just embraced it, that underdog mentality…I've learned that the best success I have is to just be me, be confident, be positive and just show everyone that you're just as capable of doing whatever it is as they are, that you don't need help or special attention, that you're just as capable."

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

And while Myers credits his parents for the way in which he approaches those situations, his father believes firmly that it's the other way around.

"Mat always had that inner confidence, that inner confidence that I say he has to have," said Marty Myers. "Nowadays, people are very, very tolerant of people with disabilities. But I've got to be honest with you, he gets the stares, he gets the points, he gets the looks - I get it, I get it…I'm not happy about it. But I'm a little embarrassed to say, Mathew is the one who has taught the people around him that that's OK.

"Mat used to be the one to teach us and say, 'Dad, don't worry about that. Let's just go, don't worry.' He never had that position of being angry or being upset of being pointed out. He always did his thing. He's really taught a lot of people the tolerance and the understanding and the compassion of being different.

"Being different isn't a negative for Mathew. It's never been a negative for Mathew. Mathew is not different to the people that know him…his friends that know him, the neighbors that know him, the community that knows him…to them he's just Mat, that's who he is."

And it's who Myers is aiming to be moving forward.

-----------------------

While right now Myers is focused on advancing his own hockey career and being the best he can be for the Boston Bruins, he hopes in the years to come that his biggest impact will be on others with dwarfism or disabilities, or those who might feel that they don't belong in hockey, sports, an office, or even society.

"I'm still trying to be the best video coach right now. I'm hoping that the rest will follow," said Myers. "I do at times kind of think back when you have those grateful moments of being at this level with this organization of the impact you may be having.

"You don't know. When I go out on the bench for warmups, there might be another little person that's watching warmups too and then looks at the bench and sees me and is like, 'I've never seen this before. There might be an opportunity. I'm curious, what's his role? That's cool.'

"I never had anyone growing up that I could look to that was my size, so I'm in the mindset right now of I'm trying to pave the path a little bit for others with dwarfism or any other physical handicap. At the end of the day, I just want to continue to be respected by the players and by peers that I can continue to grow.

"I still want to climb and look for more opportunities and growth in this sport so when I have the opportunity I can continue to give back and find ways to grow the game for others like me."

Myers also has aims of making hockey more visible and accessible for those with dwarfism. As of now, Myers said he is not aware of any hockey leagues or programs with a focus on dwarfism but would like to someday introduce the sport to the Dwarf Athletic Association, which every summer hosts people from across the United States for competitions in soccer, basketball, bocce ball, and other sports.

He'd also like to introduce hockey to the LPA (Little People of America) - an organization that the Myers family has long been involved with - by finding ways to provide hockey equipment to that community, while also forming street hockey leagues that might be safer than ice hockey for those with dwarfism.

"I think some of the issues are equipment, equipment not being accessible and it being an expensive sport. And I think because of the physicality of it, if you don't pick up hockey early, it's tough to get enough little people in the world to form leagues," said Myers. "Right now, it's more of a spectator thing…I would like to obviously try to be a pioneer and grow the game and the visibility for people of my size because it's helped me in life more than anything.

"Skating's been my thing where I can escape the world for a few minutes. It's helped me in that sense, and I want to introduce that to other little people in the world. I think we can take steps to grow the game and show that there are paths, that you don't have to have dreams of winning the Stanley Cup as a player - you can have dreams now of winning a Stanley Cup as a video coach or an equipment person or [public relations] or anything.

"There's other roles that you can still achieve that same dream…once you accept it, you can still have the same dream. You're creating your own path."

© Michael Penhollow/Boston Bruins

-----------------------

Nobody has created their own path better than Mat Myers.

Myers married wife, Amanda, this past July.

He has played hockey and soccer and baseball in a team environment.

He drives his own car. And he has graduated college.

He has made it all the way to the National Hockey League - with his hometown team to boot.

He has done all of the things that seemed so improbable when Marty and Sue Myers departed that doctor's office some 31 years ago.

Three decades after that meeting that left him with so much to ponder, Marty Myers can't help but beam with pride when reflecting on all his son has achieved.

"If you were to ever tell me back then, the list of things that Mat has accomplished…I never thought I'd even put the kid on a school bus," said Marty Myers. "I'm not blaming the doctor - we never have. I think it was just a lack of information, a lack of knowledge.

"I've got to give all the credit to Mat and how he managed it, the way he handles himself and where he's gotten himself to. I wish I could take credit for it. But he's taken us along his journey. My wife and I and his siblings are all very proud of him."

© Courtesy of Mat Myers

In the end, Mat Myers will be happy if his story can inspire even one person to follow their dreams.

"Ultimately, it's for whoever is next, whoever the next Mat Myers is - my future son down the road or another kid that's living in a small town in New Hampshire that doesn't think that this sort of opportunity exists. It's just trying to show that you can, that you can do whatever you want to do," he said.

"It doesn't have to be the dream that you see on TV. You're allowed to create your own dream and adapt to it…if you work hard, if you're positive, if you have a good attitude, you cans do whatever you want.

"Right now, I'm just trying to pave the way and grow the game and grow it more from the inside out so when the next little person walks into a locker room, it's a safe environment for them - because it's always been safe for me.

"I've always felt at home there. I've always felt confident in it. It's about just trying to bring that awareness, that someone like me can be in this environment and succeed and get the respect. That is my mission right now."

And what a mission it is.