When William Moore thinks about his future, about his approaching enrollment at Boston College and where he might focus his energies, he dismisses music right away.

How could he even consider majoring in music, in performance, in piano?

“I’m still undecided on that,” Moore said, when asked what he intends on studying. “We’ll see. Probably won’t be piano direction because I feel like I’d kind of just be cheating the system. I’d rather do something that I’d actually learn.”

Which is not to say there’s nothing left for Moore to learn on the piano. Lately, given that he’s feeling “classical music-ed out,” he’s turned away from the type of music that throughout his life was filled with pressure, the type of music on which he was tested and judged, and toward pop music, toward movie scores.

“I learned 'Interstellar,'” he said, of the 2014 movie for which Hans Zimmer was nominated for the Oscar for best original score. “That’s a fun one.”

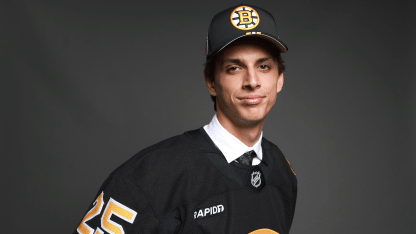

Moore, the second-round pick (No. 51) in the 2025 NHL Draft by the Bruins, has twin passions, the piano lessons that he began, startingly, at age two, and which led him to perform at Carnegie Hall in New York at age 10 after winning the Little Mozarts International Competition with his rendition of Chopin’s “Polonaise in G Minor,” and the sport he discovered on his own and could not live without.

Now Moore, an 18-year-old center, can see the next stretch of his life arrayed in front of him, starting with his enrollment at BC in the fall, and eventually leading to a spot on the Bruins, an NHL job that he has long coveted.

Of course, none of this was ever meant to happen.

“It’s surreal to think about it like that,” Moore said. “One extra month of my mom not being pregnant and I end up on the other side of the world playing a completely different sport. So I’m glad everything worked out like it did. I’m in a good spot right now. I’m very happy where I am. It couldn’t have worked out better.”