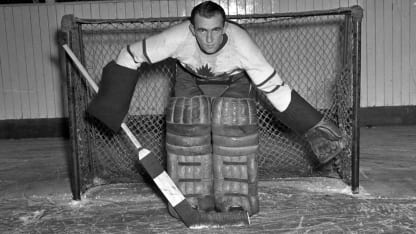

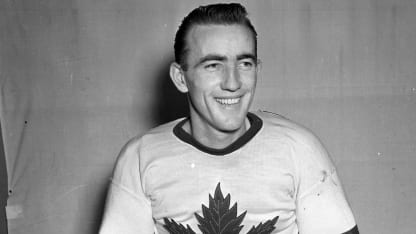

Most goaltenders would find one shutout in the Stanley Cup Final satisfying. Two would be considered a bonus. When a goaltender puts up three straight shutouts en route to winning the Cup, you'd think he'd be pretty cool about his game.

But that wasn't the case with

Frank McCool

of the Toronto Maple Leafs in the 1945 Final. On the ice, his stomach turned like an out-of-control merry-go-round. Goaltending, the toughest, most nerve-wracking job in sports, was a poor fit for the Calgary native.

McCool overcame ulcers, sparked Maple Leafs to Cup in 1945

Goaltender helped Toronto win championship in only full NHL season

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

McCool was afflicted throughout his adult life with ulcers -- the big-time, painful variety. That alone should have dissuaded him from giving up his gig as a sports writer for life as an NHL goaltender.

But 1944 was a strange year all around. World War II was raging from Europe to the Far East. As a result, some of the NHL's best players were serving in the Canadian and American armed forces, leaving the League's six teams searching for talent.

Toronto opened training camp in Owen Sound, Ontario, in search of a competent goaltender. In 1943-44, the Maple Leafs tried Paul Bibeault, who was on loan from the Montreal Canadiens, as well as Benny Grant and Jean Marois.

But the Canadiens wouldn't let Bibeault play for Toronto in 1944-45, and Maple Leafs coach Hap Day had no use for Grant or Marois. He did like what he saw in McCool, a 26-year-old with no pro experience.

"Frank quickly established himself as the team's best option, and one who didn't take his position lightly," Eric Zweig wrote in his book, "The Toronto Maple Leafs: The Complete Oral History."

How could he? Between the anxiety produced by his chosen profession and his chronic aliment, McCool had problems on top of his problems.

"Every time I feel like laughing," he once told Frank Ayerst of the Toronto Star, "I remember what those ulcers do to me and that isn't funny."

McCool won the No. 1 goaltending job and opened the season with six straight victories before the Maple Leafs slumped. However, he managed to get them into the Stanley Cup Playoffs; Toronto finished third by going 24-22 4 in a 50-game season.

But it wasn't easy.

"Every game was a life-and-death struggle for Frank," longtime Maple Leafs publicist Ed Fitkin wrote. "He sipped milk in the dressing room between periods to calm his fluttering stomach. There were times he took sick during a game. But one thing about Frank: He'd never quit."

Sure enough, McCool was good enough to win the Calder Trophy as the NHL's top rookie. But the question was whether he would be able to last through the pressure of the playoffs.

"If Frank holds up," Day declared before the postseason started, "we may surprise a great many people."

When the playoffs began, the third-place Maple Leafs faced the powerhouse Canadiens. Montreal had finished 38-8-4, and the first-place Canadiens ended the season 28 points ahead of Toronto.

McCool was unimpressed and helped

Toronto win 1-0 in Game 1

.

"McCool was a hero," Fitkin said. "He scored a shutout in the first Stanley Cup game he'd ever played."

The Maple Leafs went on to stun the Canadiens, winning the series in six games, largely because McCool outplayed six-time Vezina Trophy-winner Bill Durnan. But in the Toronto dressing room, McCool -- while being mobbed by teammates -- called out in a weak voice, "Quick, somebody, give me my milk before I faint!"

The key question for the Maple Leafs entering the Stanley Cup Final against the Detroit Red Wings was whether McCool would hold up. One person in the organization was adamant that McCool and his teammates would emerge victorious; the ever-defiant Conn Smythe, Toronto's hockey boss.

"We'll win this series," Smythe predicted. "We'll win it because we've got too good a fighting team to lose. The boys proved that against Canadiens, and they'll prove it to Detroit."

But only if McCool's ulcers held off enough for him to stay focused on stopping the puck.

The game plan, as devised by Smythe and Day, was to concentrate the line of Bob Davidson, Mel Hill and Sweeney Schriner against Detroit's best scorers.

"If it worked against the Canadiens," Smythe said, "it should work against the Red Wings."

Even in his wildest dreams, Smythe couldn't have imagined that it would work so well. Ulcers or not, McCool was unbeatable. Toronto won the first two games at Olympia Stadium, 1-0 and

2-0

, then returned to Maple Leaf Gardens, where McCool came up with his third straight shutout,

a 1-0 win

that made him the first goaltender in NHL history to have three consecutive shutouts in Stanley Cup play.

"It doesn't look like the puck is ever going to go in for us," Red Wings general manager Jack Adams said.

But forward Mud Bruneteau, the hero of Detroit's win in the NHL's longest playoff game nine years earlier, was more optimistic. Playing alongside his brother Ed, Mud figured that Toronto still was beatable.

"These Maple Leafs can't be that good," he said before Game 4. "We'll just have to go out and win four straight."

Meanwhile, McCool extended his shutout streak against the Red Wings to 188 minutes and 35 seconds before former Maple Leafs forward Flash Hollett scored at 8:35 of the first period in Game 4.

But the Maple Leafs, within one victory of the Stanley Cup, counterattacked. Ted Kennedy scored three goals; the third put Toronto ahead 3-2 entering the third period. However, McCool finally betrayed signs of fatigue and pain from his ulcers. Sparked by rookie left wing Ted Lindsay,

Detroit rallied for a 5-3 victory

.

If the Maple Leafs were worried, they didn't show it until after Game 5, in which Detroit scored twice in the third period

for a 2-0 victory

. Toronto fans had more cause for anxiety when Game 6 went to overtime tied 0-0. McCool and Detroit goalie Harry Lumley looked unbeatable that night until a bizarre bounce of the puck decided the game.

Seconds after the clock had ticked off the 14th minute of the first overtime period, Harold Jackson blooped a high shot into the Maple Leafs' zone that bounced off the wire netting far out of range of the goal. Calm to the point of unconcern, McCool awaited the response of his teammates with a counterattack after the puck caromed off the wire mesh.

It never happened. The puck struck the netting at a crazy angle and bounced back into play with unusual force, falling in front of the net. Ed Bruneteau was there and easily pushed the puck past the stunned McCool

for a 1-0 win

.

The humiliation that Toronto had foisted on Detroit in 1942 -- four straight victories after three consecutive defeats -- now confronted the startled Maple Leafs. It appeared that Detroit's superiority over Toronto during the regular season (8-1 with one tie) finally had asserted itself.

The specter of playing Game 7 on Olympia Stadium ice was just that much more proof that Toronto seemed doomed. Day examined the evidence and called a team meeting before Game 7, on April 22, 1945.

"I see by the Detroit papers," Day said, "that we are about to get beaten. I don't believe it and I hope you don't believe it. Show me a game like you did the other night in Toronto and we'll win the Cup."

Hill made Day look good by scoring 5:38 into the game, giving the Maple Leafs an early 1-0 lead. McCool kept Detroit off the scoreboard until 8:16 of the third period, when Murray Armstrong picked up the rebound of Hollett's shot and beat McCool, tying the game 1-1.

In theory the momentum should have shifted to the Red Wings. But it didn't.

At 11:55, referee Bill Chadwick penalized Syd Howe of the Red Wings for high sticking Gus Bodnar. Day immediately sent his power play onto the ice, and defenseman Babe Pratt soon became a hero.

Pratt sent a pass from the blue line to Metz, who was standing in front of the net. Lumley anticipated the move and blocked Metz's shot, but the rebound skimmed out to the onrushing Pratt, who beat Lumley at 12:14 to give Toronto a 2-1 lead.

For the final 7:46, McCool was unbeatable. Ulcers or no ulcers, he fought off the pain and helped Toronto hold on for

a 2-1 win and the Stanley Cup

.

When the ice had cleared, McCool cornered Day and, almost tearfully, whispered: "Thanks coach for sticking with me."

Day later added "Of all the boys on my team, Frank got the greatest kick out of achieving Stanley Cup eminence in his rookie year!"

Then, a pause and a postscript: "If I were to single anyone for individual praise I would have to say that McCool came farthest since training camp in Owen Sound!"

That's about as far as McCool's rewards went. He was slightly less than a hero to Smythe, who, the following autumn, refused his request for a $500 raise despite McCool's threat to retire.

"You'll probably hate yourself for the balance of your active life," Smythe warned McCool when the goaltender threatened to hang up his pads.

Though McCool eventually re-signed, he played only 22 games in 1945-46, going 10-9 with three ties as the Maple Leafs missed the playoffs. He retired for good at the end of the and eventually became sports editor of the Calgary Albertan.

McCool's stomach ailments eventually did him in. He died in 1973, at age 54. According to his daughter, ulcers were a partial cause of death.

Looking backward, Smythe was wrong: McCool was as courageous as any goaltender who ever donned the pads. What's more, he'll be remembered as the only one ever to have three straight shutouts to open a Stanley Cup Final -- and win the 1945 Cup for Toronto!

Photos courtesy of Hockey Hall of Fame