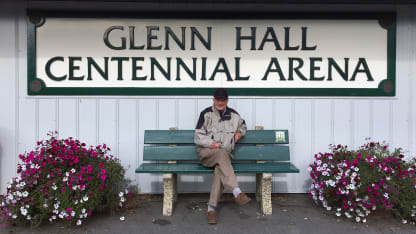

The deep, yawning fireplace in Glenn Hall's Stony Plain, Alberta farmhouse was roaring on this October evening in 2015, fed and stoked by some of the dozen people who had gathered in his spacious living room.

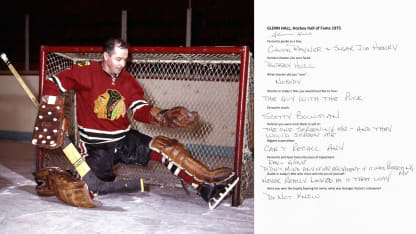

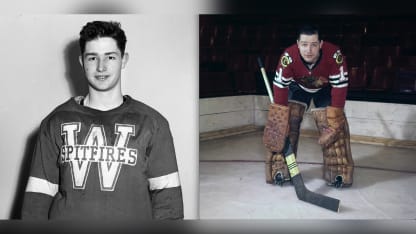

My friendship with this NHL legend had begun casually with conversations for a few newspaper stories not quite a decade earlier. But it found a new level on this visit, a bond I cherished over countless calls and a handful of subsequent visits to Mr. Goalie’s 155-acre farm, 25 miles west of Edmonton.

On Monday, Pat Hall messaged to tell me the health of his 94-year-old father, now residing in an assisted-living home in Stony Plain, had grown very fragile in the hospital, having taken ill shortly before Christmas.

“We’re taking it one day at a time and hoping for the best,” he said.