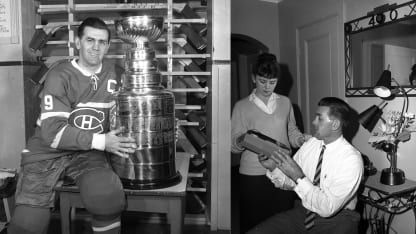

Maurice Richard with the 1960 Stanley Cup, the last of eight that he'd win, and at home in 1958 with his daughter, Huguette. Behind them is a mirror celebrating Rocket's 400th career goal, scored Dec. 18, 1954.

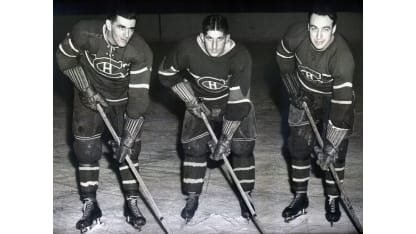

Richard wore No. 15 in his abbreviated 1942-43 season, switching to No. 9 from at the start of 1943-44. He was captain of the Canadiens from 1957-60, leading the team's final four of five consecutive championships.

Richard took No. 9 in tribute to his first daughter, Huguette, who was born on Oct. 27, 1943, three days before the start of the season. Richard didn't ask for it, however, as his life story is told.

"My father gave Rocket the morning off practice with his wife about to give birth," says Dick Irvin Jr., the late coach's son. "When Maurice returned, Dad asked him about his new child, hoping all was well with the family. When Rocket said that Huguette weighed nine pounds at birth, Dad said, 'Would you like to switch to that number?' "

Richard made the change, scoring 539 of his team-record 544 goals wearing the No. 9 that the Canadiens would retire on Oct. 6, 1960.