Not in their wildest dreams could the players and owners of the four teams that played on the NHL's first night have pictured what their league would look like 100 years later.

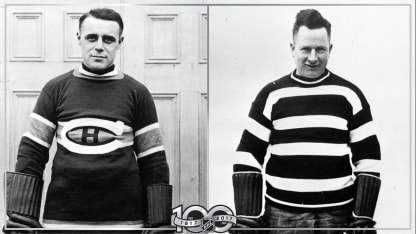

The brand-new National Hockey League began play on Wednesday, Dec. 19, 1917. "National" was more a euphemism than the 31-team reality of today -- the League included two teams from Montreal and one each from Toronto and Ottawa (a franchise from Quebec was an original member but didn't field a team until 1919). All but the new Toronto team had come from the National Hockey Association, which had recently folded.

Canadiens, original Senators helped christen NHL 100 years ago

League's first two games, featuring several future Hockey Hall of Famers, were played Dec. 19, 1917

Unlike the NHL's newest franchise, the Vegas Golden Knights, which was given ample time to get started, the four teams that played opening night were doing so 23 days after the announcement of the League's formation on Nov. 26.

RELATED: [Complete NHL Centennial coverage | 100 Greatest Players | Greatest NHL Teams ]

Modern-day NHL fans likely wouldn't recognize the sport as it was played a century ago. Forward passing was not allowed, putting an emphasis on puck-handling and skating. There were no zones, players couldn't kick the puck and what we know today as "changing on the fly" wasn't allowed. Minor penalties were three minutes, and goaltenders served their own penalties, meaning that teams had to use a defenseman or forward to try to keep the opposition off the scoreboard.

However, shooters did have one thing going for them on opening night: The NHL kept an NHA rule mandating that goaltenders weren't allowed to leave their feet to make a save; luckily for goaltenders, the rule was changed less than a month later.

Another notable thing about the NHL's opening night: The four teams included a Who's Who of hockey history.

The visiting Montreal Canadiens defeated the Ottawa Senators 7-4, with Montreal forward Joe Malone scoring five goals on his way to finishing with 44 in 20 games. In addition to Malone, Montreal's roster included goaltender

Georges Vezina

and players such as Newsy Lalonde, Didier Pitre and Jack Laviolette. Ottawa featured its own star goaltender, Clint Benedict, as well as Eddie Gerard, Cy Denneny and Jack Darragh. All have been inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Ottawa trailed 3-0 after the first period, which saw Darragh and Hamby Shore each refuse to play until his contract was reworked. They appeared during the second period after agreements were reached, but, according to the Globe and Mail, "it was too late to repair the damage" for the original Senators (1917-34).

The game, played at Dey's Arena, reportedly drew about 6,000 fans, though the building's normal seating capacity was listed at 4,500.

"Between five and six thousand people turned out to attend the local game," the Toronto Sun reported, "and though the ice was sticky, preventing the Ottawas from showing their usual speed and helping the heavier Canadiens, the hockey dished up was, under the circumstances, surprisingly good.

"Had the Ottawas started out with their regular team they might have landed the match."

The Montreal Wanderers opened at home with a 10-9 victory against the Toronto Arenas. Wanderers defenseman Dave Ritchie scored the first goal in NHL history one minute into the game, which started earlier than the Senators-Canadiens game, and Harry Hyland scored five for Montreal. Reg Noble scored four goals for Toronto. Art Ross, who earned induction into the Hall of Fame as a builder for his work with the Boston Bruins, was a reserve for the Wanderers and scored his lone NHL goal at 17:30 of the second period. It was described by Le Canada, a French-language daily newspaper, as the "most beautiful of the night."

Bert Lindsay, father of future Hall of Famer

Ted Lindsay

, was the goalie for the Wanderers. Goalie Sammy Hebert began the game for Toronto but was replaced by Art Brooks. The Globe and Mail blamed Toronto's goalies for the loss.

"The play was somewhat ragged at times and the visiting team was weak in its goalkeepers. Toronto had the better of the argument most of the game, but neither Hebert, who was the Toronto goalkeeper in the earlier part of the game, nor Brooks, in the second session, stopped the Wanderers' shots as they might have done."

Unlike the packed house in Ottawa, the Wanderers drew 700 people at Westmount Arena despite offering free admission to military personnel and their families.

The Wanderers' opening-night victory turned out to be their last. They lost their next three games before a fire burned down Westmount Arena on Jan. 2, 1918. The Canadiens, who also used Westmount as their home, moved into the 3,250-seat Jubilee Rink in the city's east end; the Wanderers elected to fold.

It wasn't easy, but the three-team NHL made it to the end of the season. Not only that; it brought home the Stanley Cup. Toronto defeated the Canadiens 10-7 in a two-game, total-goals series, then topped the Vancouver Millionaires, champions of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, in a five-game final, enabling the new league to proclaim itself as the world's best.