In February 1910, a Montreal professional team from the relatively new National Hockey Association, les Canadiens, traveled north to play an exhibition game against the Chicoutimi club before at least 800 locals who packed the city's lone indoor rink. Legend has it that the 23-year-old Vezina shut out the big-city pros, but further research has shown that Chicoutimi led 7-1 at halftime and 11-5 at the end, with Vezina the game's top star.

Before departing for Montreal, Canadiens goalie and coach Joe Cattarinich offered Vezina his job tending goal. Cattarinich was more interested in coaching and managing and recognized that Vezina would be an excellent upgrade. Vezina either rebuffed Cattarinich's initial offer or needed more time to consider it.

Prior to the following season, the Canadiens - recently bought by George Kennedy -- renewed their offer, and this time the 23-year-old Vezina accepted. His older brother Pierre, a teammate in Chicoutimi, traveled with him to Montreal, invited to try out. Pierre didn't make the club, but Georges did, shaking hands with Kennedy to play that season for $800. Vezina would never sign a contract; a gentlemen's agreement was enough.

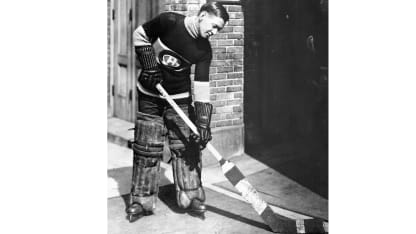

He led the NHA in GAA in his first two seasons, even though the Canadiens were no better than a .500 club. Taking on Portland for the Stanley Cup in 1916, the Canadiens defeated the Rosebuds in five games. "Much of the Canadiens' first Stanley Cup victory could be attributed to goalkeeper George Vezina," Henry Roxborough wrote in his book "The Stanley Cup Story." The 29-year-old goalie surrendered 13 goals for a 2.60 average, well below a typical number of the time.

The night of the Cup-winning game, Georges' wife, Marie, supposedly gave birth to the couple's second child. "I'm going to name him Stanley," the goalie reportedly told Kennedy. "Marcel Stanley Vezina will be his name." Recent research has shown, however, that the boy was actually born the day after the Canadiens' Cup victory and that his given name was Joseph Louis Marcel Vezina -- but everyone called him "Stanley" nonetheless, perhaps because famous photos later appeared of the baby sitting in the Cup.

Vezina helped the Canadiens reach the Final again in 1917. The NHL was born the next season, and Vezina led all goalies in wins (12) and average (3.93). He also recorded the NHL's first shutout on Feb. 18, 1918.

The next season, he led the Canadiens back to the Cup Final against the Seattle Metropolitans. They had played five games when the series, being played in Seattle and tied 2-2-1, was canceled because of the flu pandemic that struck seven of the Canadiens and Kennedy. On April 5, 1919, four days after the cancellation, Canadiens defenseman Joe Hall died. Kennedy, who never fully recovered, died in 1921.

At age 36 in the 1922-23 season, Vezina cut his average by more than a goal a game from the previous season, to 2.46, leading the Canadiens into the playoffs against the powerful Ottawa Senators. In a two-game, total-goals series so vicious that Dandurand would suspend two of his own players, the Senators prevailed on a late Game 2 goal, firing 65 shots at Vezina (some reports said 79). He stopped all but the one.

In 1923-24, Vezina established an NHL record with a 1.97 GAA and the Canadiens beat the Senators for the NHL championship before recapturing the Cup by defeating the Vancouver Maroons and the Calgary Tigers. In their four Stanley Cup Playoff games out west, Vezina allowed four goals, with a shutout in the Cup-clinching game.

He followed that up the next season, at 38, with an extraordinary average of 1.81.

But Vezina reported to team in the fall of 1925 looking thin and pale. While he brushed off all inquiries about his health, he could not hide his discomfort on opening night against the Pittsburgh Pirates, when he struggled to play with a high fever. Until he collapsed, true to his restrained nature, he'd alerted no one about his illness.

Following a doctor's diagnosis, Vezina returned to Chicoutimi to live out his final days. He would be inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1945.

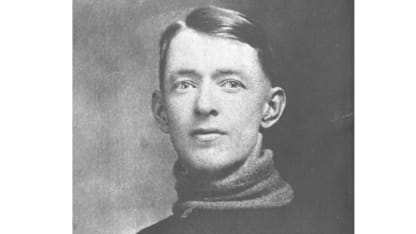

In 1927, Canadiens ownership - Dandurand, Cattarinich and Louis Letourneau -- donated the Georges Vezina Memorial Trophy in his honor. In that twinkling galaxy of silver NHL trophies, it is perhaps the most immediately symbolic, an open-walled church of hockey with a miniature goal as its altar. Above that rises a steeple topped off by a puck on its edge, with a beaver perched on the puck. Below, in bas-relief, are crossed goal sticks encircled by a wreath. Further down, affixed to the wooden base, is an engraved picture of Vezina, wearing his toque and his best Mona Lisa smile.

If the donors' intention was to create something that would perpetuate the great goalie's name long after his death on March 27, 1926, they succeeded.

For more, see all 100 Greatest Players