Penguins blood has coursed through Binkley since the beginning, the native of Owen Sound, Ontario, on the roster from day one. Look up "pay your dues" in the dictionary and there's a photo of "Bink," who wore 15 different jerseys from his junior debut in 1949 through his retirement from pro hockey in 1976.

And what a journey, one that famously included being scored upon twice by future motorcycle daredevil Evel Knievel in a WHA penalty-shot promotion at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto.

To his credit, Binkley stopped two Knievel tries in the four-shot caper and, in a later promotion, denied a hot-shot 12-year-old whose eyes grew wide at the five-hole the goalie deliberately left open before slamming it shut.

"And I don't think to this day that Wayne Gretzky can believe he didn't score on that one," Binkley said.

In 1971 with the Penguins, he surrendered the 544th career goal by Chicago Blackhawks sniper Bobby Hull, which then briefly tied "The Golden Jet" with retired Montreal Canadiens icon Maurice Richard for second place on the NHL's list.

Three years earlier, Binkley had yielded the milestone 700th goal of Detroit Red Wings legend Gordie Howe.

But the goalie's list of highlights more than balances his ledger:

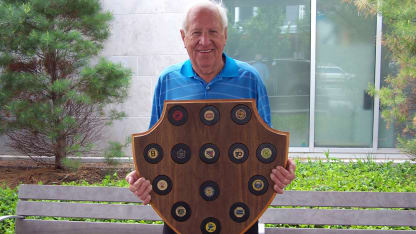

He earned a remarkable six shutouts in 54 games for the 1967-68 expansion Penguins; he had a goals-against average of 3.12 through his 196 regular-season games, often playing in front of a screen-door defense; he shut out the Canadiens 4-0 on home ice on March 3, 1971, his last of 11 career shutouts, with 23 of Montreal's 33 shots that night coming off the sticks of future Hall of Fame members; and in 2003, he was inducted into the Penguins Hall of Fame.

In his 1969-70 playoff run, Binkley went 5-2 with a 2.10 GAA and a then-tremendous save percentage of .924 before a chronically, surgery-bound knee left him unable to play.