McCool tried to use ulcers as bargaining chip with Maple Leafs in 1945

Goalie who had painful condition, won Cup as rookie was out of NHL after failed negotiation

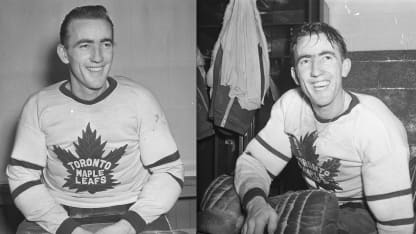

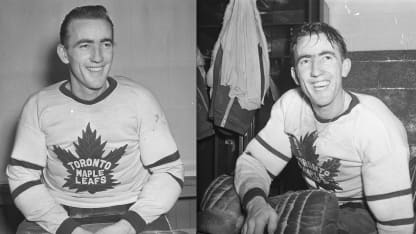

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

Goalie who had painful condition, won Cup as rookie was out of NHL after failed negotiation

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame