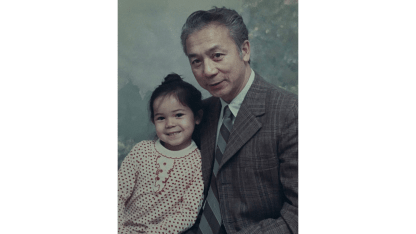

Kristina Heintz didn’t even know her father, Larry Kwong, had played in the NHL until a relative mentioned it to her offhandedly when she was 11.

That was the type of quiet pride her dad, trailblazing forward Kwong, conducted himself with throughout a lifetime both within and beyond the world of hockey. As the first player of Asian descent in NHL history – and the first non-white not of indigenous descent to break into the league a year after Jackie Robinson shattered baseball’s “color barrier” in 1947 – Kwong didn’t exactly wear his unique legacy on his sleeve.

“He was kind of raised to be like, keep your head down and don’t draw attention to yourself or the family,” Heintz, 56, said. “Because they already were different. So, he was raised that way and he kind of carried that mantra with him throughout his life.”

Heintz and her daughters, Madison, 23, and Samantha, 25, will be on-hand at Climate Pledge Arena on Tuesday, Jan 28 to celebrate Lunar New Year Night, pres. by Alaska Airlines. Alaska will be providing them with round-trip flights to and from the game. The Kraken plan to honor Kwong, who died in March 2018 at age 94, at that night’s game against the Anaheim Ducks by giving his daughter and granddaughters a Kraken jersey celebrating his 1948 feat and its impact on future generations of Asians playing professional hockey.

Kwong will also be the night’s “Hero of the Deep” and a $32,000 donation will be made by the Bonderman family of Kraken majority owner Samantha Holloway to two non-profits supporting the Asian American community.

Lunar New Year Night is part of a continuing Common Thread series of themed Kraken games – highlighting the team’s commitment to diversity and inclusivity through yearlong community initiatives. It symbolizes the idea that regardless of our diverse backgrounds and unique experiences, we are all woven together by the same passion and devotion to our team.

The program takes a deeper look at growing the game of hockey and its impact extends beyond a singular game celebration within a season.

When it comes to Kwong, a singular game wearing his No. 11 was all he was given to make history. In fact, a singular shift at the end of that March 13, 1948 game in Montreal against the Canadiens and scoring legend Maurice “The Rocket” Richard was all the New York Rangers afforded Kwong – their best minor league player at the time.

It would be the only shift of his NHL career.

Heintz said her father never mentioned “racism” or “discrimination” as being behind his limited stint, despite the fact he led the Rangers’ New York Rovers farm club in scoring at the time and other players from that squad subsequently got greater NHL playing time than he did. But she said he knew there was likely more to that decision than his playing ability; he'd already been singled out plenty as a Canadian of Chinese descent growing up in Vernon, B.C.

“He never outright said it because my dad’s not the kind of person to go around and say things he didn’t know for a fact,” Heintz said. “Nobody ever came to him and said: ‘You did not play hockey because you were Chinese.’ But in his gut, he always suspected he was different. There was a lot of racism at the time. A lot more racism, from the stories my family tell me, than there was when I was growing up.”