MONTREAL --The stories, so many of them through time, have painted

Howie Morenz

in a dark, brooding light.

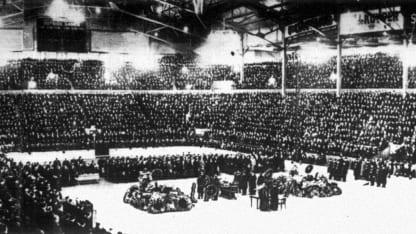

Perhaps the first true superstar of the NHL, Morenz died 80 years ago Wednesday, on March 8, 1937, five weeks after he sustained multiple fractures of his left leg during a game against the Chicago Black Hawks at the Montreal Forum.

Morenz's career had ended Jan. 28, 1937, when he tripped along the boards and was pinned to the ice beneath Chicago defenseman Earl Seibert. Morenz was transported to St. Luke's Hospital, his leg shattered in four places. Late on the night of March 8, Morenz died from a coronary embolism, a clotting of the blood.

Remembering Howie Morenz, NHL's first superstar

'Babe Ruth of Hockey' died 80 years ago Wednesday

© B Bennett/Getty Images

© 2001 SNOWBOUND, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED