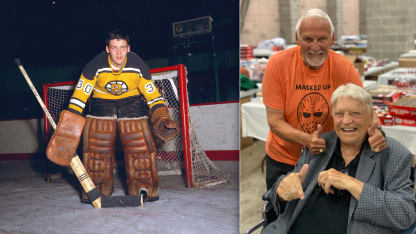

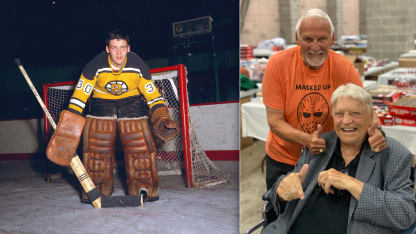

Gerry Cheevers, age 20, with Toronto Maple Leafs teammate Dick Duff before the start of the 1961-62 season. Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

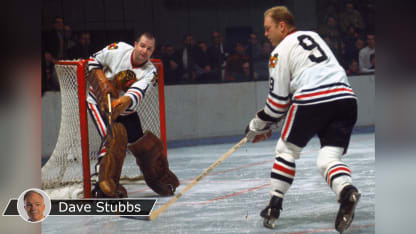

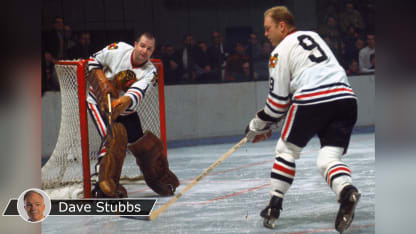

"The first time you faced Bobby was sort of exciting, in the wrong way," Cheevers said. "He was the best shooter in hockey, a power shooter. It became worse when his brother, Dennis, arrived (with Chicago in 1964-65). Bobby didn't scare me as much as Dennis. Bobby usually scored. You had no idea where Dennis was going to shoot."

Cheevers remembers the big picture of the Golden Jet, whom he believes was perfect for that era of the NHL and tailor-made for Chicago Stadium, his blazing speed scorching a rink surface that was 15 feet shorter than the now-regulation 200 feet.

"Bobby was an exciting player, to say the least," Cheevers said. "He had flair and charisma, a great smile, he had a bunch of that stuff. And he had the luxury of playing in sort of a condensed rink.

"He was a pioneer, like Ted Lindsay was in the creation of the NHL Players' Association. When Bobby made the move to the World Hockey Association (signing a historic $1 million contract with the fledgling league's Winnipeg Jets in 1972-73), that was to me one of the most important things in the game of hockey.

"If he wouldn't have made the move, I know I wouldn't have gone (signing that year with the Cleveland Crusaders) and a lot of guys wouldn't have gone. There might not have been a league. The WHA created a big-league atmosphere for hundreds of players who might not have had it with the NHL. Bobby, and the WHA, gave a lot of guys the chance to play."