For decades goaltenders never would think of donning a mask. But then again, why would they?

In the years leading up to World War I and the formation of the NHL in 1917, shots on goal were rarely as dangerous, and certainly not nearly as hard, as blasts from today's players. But by the end of World War II the NHL had become faster and more furious than ever, and so were the shots on goal.

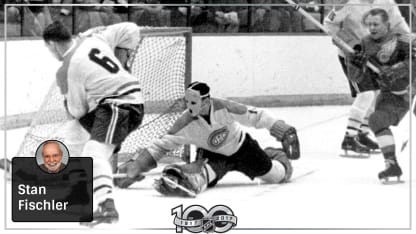

Plante revolutionized hockey by donning mask

Montreal goalie began new era by wearing facial protection in NHL game Nov. 1, 1959

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Maurice "Rocket" Richard, with his backhand drive alone, could propel a puck at speeds of more than a mile a minute. When his teammate, Bernie "Boom Boom" Geoffrion, developed a slap shot at even faster speeds, goalies were in big trouble.

Hockey Hall of Fame goaltender Glenn Hall once told me in no uncertain terms, "Goaltending is sixty minutes of hell." Hall's teammates had no doubts about his statement; they watched him vomit before every game. Yet Hall, who starred on the Chicago Blackhawks' Stanley Cup-winning team in 1961, played 502 consecutive regular-season games without facial protection.

As it happened, one of Hall's contemporaries, Jacques Plante of the Montreal Canadiens, began getting the notion that being playing goal without a mask was a bad idea. Ever creative, even as a junior player, Plante began experimenting with the idea of a face protector.

At first he did it surreptitiously, and for good reason: He knew that Montreal coach Toe Blake would dismiss the idea of a goalie mask out of hand.

But Plante was as determined as Blake was stubborn. What's more, he found a craftsman who could mold a plastic face protector with eye and mouth slits that Plante eventually would use for practice. By this time Plante had summoned enough courage to confront his coach and demand that Blake at least allow him to don his mask during scrimmages. Plante reasoned with that the Canadiens had some of the NHL's hardest shooters, including Richard, Geoffrion, Jean Beliveau and Dickie Moore. Why get hurt in practice?

Blake began thinking along the same lines. He realized he had one goalie and certainly did not want him unnecessarily injured in a workout. Blake finally agreed, reluctantly, that practice shots by Richard, Geoffrion, Moore, Beliveau and their teammates could present a hazard, so he allowed Plante to give his revolutionary plastic mask a try.

Also, Plante's goaltending had spearheaded the Canadiens to four straight Stanley Cup championships. In a sense, Blake figured he owed his goalie a favor. Ergo, Plante could wear his mask at practice.

That said, absolutely no one believed that Blake would allow a masked goalie during regular-season games. Nobody disagreed with Blake, and yet Plante eventually would win the argument in the most ironic way.

This is how it slowly evolved:

Plante had developed a nasty habit of occasionally fouling his opponents. One of those opponents happened to be New York Rangers star right wing Andy Bathgate, who never liked gratuitous slashes to his knees. In previous games between the teams Plante had enraged Bathgate with some whacks that clearly were illegal.

Bathgate refrained from retaliation until the Canadiens came to Madison Square Garden on Nov. 1, 1959. Early in that game Plante tripped Bathgate and nearly injured him.

"I felt that I had enough of that stuff from Plante," Bathgate said decades later when he returned to the Garden for an interview. "I had decided I would get even."

And he did. Shortly thereafter, Bathgate raced down the right side and unleashed a shot that Plante was ill-prepared to stop.

"I was aiming for his head," Bathgate said. "And it was a backhand shot, not a snap shot the way others later reported."

To this day goaltenders will tell you that the backhander is the most challenging of shots because it resembles a knuckleball in baseball. Sure enough, before Plante could duck, the puck struck him squarely in the nose and sent him crashing to the ice. His face looked like a mashed potato covered with ketchup.

Stunned and bloodied, Plante was helped to the dressing room where he needed seven stitches in his nose. For several minutes nobody could be sure that he would be fit to play again. And presuming that he had to be hospitalized, then what?

In those days NHL teams didn't carry a backup goalie. However all six arenas had to provide what was known as a "house goalie," usually an amateur who played in a local beer league. During the 1959-60 season, New York employed two house goalies. One was Joe Schaefer, who played in the Metropolitan League for the Sands Point Tigers. The other was a well-known television director, Arnee Nocks. The Brooklyn native doubled as the Rangers' practice goalie, though he was better known for his work on a popular 1950s kids TV show called "Captain Video and His Video Rangers."

On this night, Nocks was in the Garden watching when Bathgate's shot smashed into Plante's face. As the Montreal goaltender was carried off the ice, Nocks dashed to the visitors' dressing room, knowing that Plante might not return and a replacement would be needed.

Unbeknownst to Nocks, while Plante was having his face rearranged he also warned Blake that he absolutely would not return to the ice unless he was allowed to wear his new mask. While the two argued, Nocks proceeded to attach his goalie pads and assorted other equipment before putting on the bleu, blanc et rouge Canadiens jersey.

During his shouting match with Plante, Blake occasionally peered over at Nocks and realized that the talented Rangers just might beat his Canadiens. He wanted no part of that. Losing two points because he had to use a beer-league goalie? Never!

Blake finally turned to his Vezina Trophy-winning goalie and said, "OK. Do it." Moments later, Plante left triumphantly trundled out of the dressing room, clomping along the yards of rubber matting before climbing the dozen stairs that led to the ice.

I was at the Garden for this unusual Manhattan melodrama. Along with 15,000-plus spectators, I was in a state of disbelief when the masked goalie skated to the Montreal net. Like others in the crowd I was shocked not only by Plante's grotesque mask, but furthermore that a goaltender actually was wearing one as a regular piece of equipment.

Now another question emerged in the press box overhanging the mezzanine at the Garden: Could Plante make his masked experiment work? The answer was yes. He and the Canadiens defeated the Rangers 3-1 that night, the beginning of a 10-0-1 unbeaten streak. Plante was in goal for all 11 games.

Still unconvinced, Blake pleaded with Plante to try playing another game without a mask, and finally the goalie agreed. The result was a bad loss for the Canadiens, and Plante never played without a mask again.

Better still, he won another Vezina Trophy and backstopped the Canadiens to an unprecedented fifth consecutive Stanley Cup.

The legacy of Plante's decision is evident in today's game. Not only are all goaltenders required to wear a mask, but teams must dress two goalies for every game. And when a goalie's mask comes off during a game, the whistle is blown and play is stopped.

"Plante changed the game forever," author Andrew Podnieks wrote in his 2003 book, "Players: The Ultimate A-Z Guide of Everyone Who Has Ever Played in the NHL."

And to think that the goalie revolution all began with an Andy Bathgate revenge backhand!