DETROIT --Joe Louis Arena sits in a spot on the Detroit River that would be nice if not surrounded by a convention center, a freeway, a parking structure and an apartment complex.

The roads around it are falling apart. The sidewalks are cracked. The metal is rusting.

Joe Louis Arena 'beautiful in its simplicity'

Inside walls, unique history of beloved home Red Wings are leaving

To access the building from the street, fans must climb 36 steps. Critics once questioned if the steps would be safe in winter and recommended they be enclosed.

The Joe is a spartan gray box of cinder block and siding. There are no windows, except for small squares on three nondescript doors. There is no loading dock, so when deliveries arrive, trucks come right into the bottom level through one big gate, and, often, so does cold winter air. There was no press box until one was retrofitted, and it's tight.

© Dave Reginek/Getty Images

The concourses are crowded. The bathroom lines are eternal. The stairwells smell. The main scoreboard still has small standard-definition screens, and the out-of-town scoreboards haven't worked for years. The company that made them went out of business, so they can't be fixed. They have been covered with banner ads for a tire store.

The suites are all on the top level. The seats everywhere are worn.

The Joe is scheduled to be demolished later this year to clear the land for redevelopment.

"In terms of architecture, good riddance," Detroit Free Press business columnist John Gallagher wrote in the newspaper's commemorative book, "The Joe."

If you didn't know better, you'd wonder why people are so emotional about the last game there.

The Detroit Red Wings will play the New Jersey Devils in the finale at the Joe on Sunday (5 p.m. ET; SN1, FS-D, MSG+ 2, NHL.TV), then move into the state-of-the-art Little Caesars Arena next season.

But a building is just a building. The moments and the people are what make it beloved.

Detroiters didn't want to leave Olympia Stadium for Joe Louis Arena in December 1979. The Olympia was where the Red Wings became the Red Wings, literally. They were the Cougars when the Olympia opened in 1927, became the Falcons in 1930 and then the Red Wings in 1932.

The Olympia housed seven Stanley Cup teams. It was where Gordie Howe, Ted Lindsay, Sid Abel, Terry Sawchuk, Alex Delvecchio and so many others became legends.

So people loved the red brick barn for the balcony, the intimacy and the sounds it amplified. When the Red Wings left for Joe Louis Arena, they had missed the playoffs 11 times in 13 years. All people had to hold on to was the past.

Now Detroiters are sentimental about the Joe, where the Red Wings became the Red Wings again, in a sense. During the past 37-plus years, it has become another version of the Olympia.

© Dave Reginek/Detroit Red Wings

The Joe has housed four Stanley Cup teams. It is where Steve Yzerman, Nicklas Lidstrom, Sergei Fedorov, Pavel Datsyuk, Henrik Zetterberg and so many others became legends.

So people see its flaws as character and celebrate its virtues. With the death of owner Mike Ilitch on Feb. 10 and the Red Wings missing the postseason for the first time in 26 seasons, people are holding on to the past again.

"It's the same thing," said Paul Woods, who played forward for the Red Wings from 1977 through 1984 and has been their radio analyst since 1987. "It's just a different time."

The Joe seems older than it is. It is particularly unique among NHL buildings because it imported so much history from the Olympia and hosted so much history itself while fancy arenas popped up across North America.

It is the last NHL rink you can call a barn other than, perhaps, the Scotiabank Saddledome in Calgary, built in 1983. It is the second-oldest building in the League aside from Madison Square Garden, which underwent a large-scale renovation that was finished in 2013.

It helps that Detroit is a blue-collar town that values tradition and grit.

The steps that were unsafe? They've become iconic. The lack of amenities? They serve as a badge of honor; the game is the sole reason for being there. If all the suites are up high, the players feel the fans are close. It doesn't matter if your seat is worn if you are on the edge of it.

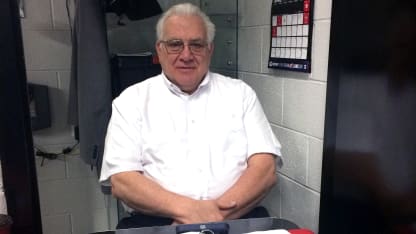

The maintenance guys reupholster those seats and replace the springs so they snap back up. They keep the place clean. Al Sobotka, the building manager since the Joe opened, will take you underneath the stands, where beer and popcorn spill. The floors are spotless. The crew uses old hockey stick shafts to extend the broom handles to reach every nook and cranny.

Sobotka takes offense when people call the Joe a dump. "You know what?" he said. "There's a lot of us in this building, starting with me, who have a lot of pride in what we do here. We take care of it the best way we can."

© Dave Reginek/Getty Images

By today's standards, the Joe is intimate and the sight lines are excellent. The lights are bright. The ice is hard. The end boards are lively, the last in the NHL still made of wood. Behind the thin layer of white plastic, there are two layers of plywood painted red, supported by a steel frame. Lidstrom, the Hall of Fame defenseman, used to fire point shots wide on purpose so the puck would ricochet in front.

And the sound? Loud.

"I thought it was a great building to play in," said Yzerman, who captained the Red Wings through their most recent glory years and is now the general manager of the Tampa Bay Lightning. "Every time you stepped on the ice for a game, you were always excited to play the game. It just had a really nice atmosphere in there. It was beautiful in its simplicity."

It was no ordinary Joe.

* * * * *

The Red Wings were supposed to move from Olympia Stadium in the city to the northern suburbs. They planned to build Olympia II, an arena of about 15,000 seats, slightly larger than the original, across the street from the Pontiac Silverdome.

But the city of Detroit was building a 20,000-seat arena on the riverfront, and had no tenant. Long story short, the city offered the Red Wings a sweetheart deal to move into its arena. The city council named it for Joe Louis, the heavyweight champion boxer who grew up in Detroit.

It was, as the Free Press wrote, "a drab, functional public works project."

When the Red Wings played the Quebec Nordiques in the finale at Olympia Stadium on Dec. 15, 1979, the fans booed the mention of Joe Louis Arena. When the Red Wings played their first game there 12 days later, the fans booed every mention of it then too.

The Free Press called it "Louis Arena" on second reference at the time, not "the Joe." The city wasn't on a first-name basis with the new arena yet.

At best, the newspaper reported, the early reviews were mixed. One fan complained it was too big and you couldn't hear the sounds of the game, like puck hitting stick. Another complained that, though it didn't have posts to obstruct the view like the Olympia did, the pitch of the seats was too shallow and you couldn't see over the person in front of you.

Red Wings coach Bobby Kromm said the first game there was like a road game. Forward Errol Thompson said the fans were too far away.

"The feeling wasn't good, to tell you the truth," Woods said. "We liked it so much at Olympia."

The most memorable moments from Joe Louis Arena's early days were more about what happened at the Olympia. On Jan. 12, 1980, the fans chanted Howe's first name as his Hartford Whalers defeated the Red Wings 6-4. On Feb. 5, 1980, the fans stood, cheered and chanted "Gordie!" for an extended period after he was introduced last by the public address announcer during his 23rd, and final, NHL All-Star Game. On March 12, 1980, 19 days before his 52nd birthday, they saw him play one last time in a 4-4 tie.

"It all started here," Howe said.

He meant Detroit, not Joe Louis Arena.

The Red Wings were awful back then. They had 2,100 season-ticket holders and an average attendance of maybe 7,000. Pressure built on owner Bruce Norris to sell. Finally, he had enough and sold to Ilitch for $8 million in June of 1982.

Ilitch spent about $400,000 renovating an arena that was 2 1/2 years old. He redid the locker room and adjacent press room. He redid the pro shop. He painted the fan area, draped red-white-and-blue bunting from the ledges and hung murals of Red Wings greats above the front doors.

"I want the fans to feel they're in a hockey setting as much as Olympia Stadium," Ilitch told the Free Press. "I can't do it overnight, but I'm embarking on it."

When he was introduced before the 1982-83 home opener, Ilitch received a standing ovation and got choked up. He gave away a car that night, the first of a fleet he gave away trying to draw fans.

The Red Wings were still awful. But after that season, they selected Yzerman with the No. 4 pick in the 1983 NHL Draft. Ilitch spent hundreds of thousands of dollars more on paint, murals, lighting and a renovated Olympia Club, hoping to transform the arena, as he would describe it, into the jewel of the riverfront.

As the Red Wings rose to prominence, the fans filled the stands, and the energy built at the Joe. The Red Wings made the Campbell Conference Final in 1987 and 1988, losing to the powerhouse Edmonton Oilers each time. In 1990-91, they started a streak of 25 consecutive playoff appearances. In 1993, they hired Scotty Bowman as coach, already in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

A fan threw an octopus on the ice late in the 1993-94 season. The tradition had started at the Olympia in 1952, the eight legs representing the eight playoff wins needed to win the Stanley Cup at that time, but had waned as the Red Wings struggled through the years.

This time, for some reason, Sobotka raised the octopus over his head and spun it like rally towel after he had raced onto the ice to clean up the mess. The Joe responded with a roar.

"When I gave it a twirl," Sobotka said, "that's what started it all."

© Dave Reginek/Getty Images

Fans threw more and more octopuses as the Red Wings made the Stanley Cup Final in 1995 for the first time in 29 years. They were swept by the New Jersey Devils.

Sobotka became a local celebrity, as recognizable as a player.

They won an NHL-record 62 games in 1995-96 but lost to the Colorado Avalanche in six games in the Western Conference Final, when Avalanche forward Claude Lemieux hit Kris Draper and sparked a bitter rivalry.

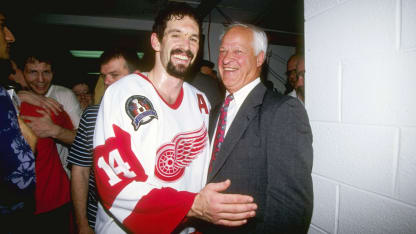

The Red Wings avenged Draper and jelled in a fight-filled, comeback victory against the Avalanche at the Joe on March, 26, 1997, a date many Detroiters know by heart, and then went on to defeat them in the Western Conference Final en route to their first Stanley Cup since 1955. Darren McCarty scored the Cup-clinching goal at home as the Red Wings swept the Philadelphia Flyers.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

"We've had some disappointments, and we've broken people's hearts," Yzerman said afterward. "But they kept coming back, every year, cheering louder."

The drab, functional public works project was now the home of "Hockeytown," the marketing label the Red Wings created and the city happily adopted. The arena no one wanted was now the place everyone wanted to be, except opponents.

"For us, there was not one time you walked in that arena not being nervous," former Avalanche forward Peter Forsberg said in January. "You knew it was going to be a battle. If you're not awake for the first minute, you're going to be outplayed."

Perhaps there's no bigger compliment than this:

"I'm kind of glad they are tearing it down," Forsberg said.

The Red Wings won the Cup again in 1998, 2002 and 2008, clinching it at the Joe in 2002. They went to Game 7 of the Final in 2009, losing to the Pittsburgh Penguins at home. They set the NHL record for longest home winning streak at 23 games in 2011-12. Think of all the coaches and players who came through the Joe: Bowman, Mike Babcock, the Hall of Fame players, the "Grind Line" guys ...

"It's got its own incredible charm, but she was home," Red Wings general manager Ken Holland said. "She was home to all that."

© Harry How/Getty Images

Walk in as a fan now, and the concourses are filled with photos, statues, logos, even a walk of fame on the floor. So many banners hang from the rafters, it's a wonder the roof doesn't fall in.

Walk in as a Red Wings coach or player, and you cut through the Olympia Club, the walls lined with black-and-white photos of Red Wings past. You emerge near the locker room, where the walls display the names of champions and trophy winners. You walk down the hallways and into the locker room. Plaques. Photos. It's a museum as much as a workplace.

"Everything that's been accomplished in this building, the Cups and the battles that's been going on, it really is in the walls," Red Wings defenseman Niklas Kronwall said. "Of course the new building is going to be unbelievable, off the charts, but this place is very special. I think everybody that has ever played here, whether you played here for Detroit, or coming into this building, knows that this is a special place."

* * * * *

Though Joe Louis Arena hosted other events -- including the 1980 Republican National Convention, NBA and college basketball games, boxing and wrestling matches, ice shows and concerts -- it was mostly a big community hockey rink. Youth and college teams played there, as well as the NHL teams. Some kids climbed the ladder from the bottom up.

Mike Modano grew up in the Detroit suburbs and played for and against Ilitch's Little Caesars youth program. He practiced and played at the Joe, grabbing sticks discarded by NHL players. He played against the Red Wings at the Joe for years with the Minnesota North Stars and Dallas Stars before ending his Hall of Fame career with Detroit in 2010-11.

© Dave Reginek/Getty Images

Doug Weight grew up in the city. He played against Little Caesars, won a Central Collegiate Hockey Association title with Lake Superior State and played against the Red Wings with six NHL teams at the Joe.

"My first game here was pretty special," said Weight, the coach of the New York Islanders. "I think my first faceoff was against Stevie [Yzerman]. I'm thinking, 'What in the heck is going on here?' I grew up watching these guys."

Bryan Rust grew up in the suburbs and scored in a shootout between periods of a Red Wings game at the Joe when he was about 8. He played for and against Little Caesars at the Joe. He won a CCHA title at the Joe with Notre Dame and has played against the Red Wings there for the Penguins.

"It makes me a little bit nostalgic, just knowing what this place has meant for my hockey career, for my family's love of hockey, all my friends who love hockey," Rust said.

Justin Abdelkader (Michigan State), Danny DeKeyser (Western Michigan), Luke Glendening (Michigan) and Dylan Larkin (Michigan) each grew up in the state, played at the Joe and now play for the Red Wings.

As a child, Larkin would find tickets to a Maple Leafs-Red Wings home game in his stocking at Christmas. He went to his first NHL game there when he was 5 or 6, played his first game there when he was 8, and played there in college.

"Almost every day, I kind of have to pinch myself and realize I'm playing here," Larkin said.

Seated at his stall in the locker room, he looked across at framed photos of Lidstrom and Yzerman. He looked to his right at 11 cutout photos of the Stanley Cup, representing the Red Wings' 11 championships.

"Everywhere you look," he said, "it's just history and reminders of the great players who came before."

© Dave Reginek/Getty Images

Everywhere you look, there are familiar faces too. If only we could name them all.

Senior vice president Jimmy Devellano has been with the Red Wings since 1982. Holland has been with them since 1983, when they signed him as a minor-league goaltender. He became a scout and rose to GM in 1997.

Former players like Draper (special assistant to the GM), Woods (radio analyst), Chris Chelios (assistant coach), Kirk Maltby (pro scout), Chris Osgood (studio analyst) and Mickey Redmond (TV analyst) are still working at the Joe.

Statistician/historian Greg Innis started with the Red Wings during the 1974-75 season but has been going to games even longer. He said he has missed 12 home games since March 27, 1969.

Five members of the off-ice officiating crew have been working at the Joe for at least 25 years. One goes back to the Olympia.

There are 126 arena workers who have been at the Joe for at least two decades. Five started at the Olympia.

Walk into the Joe as a reporter, and Betty Malone (12 years) checks your bag. Walk down the hall, and Joe Quaiatto (21 years) makes sure you have your credential. Walk a little farther, and Sobotka (46 years) is buzzing around on the forklift.

Sobotka started at the Olympia in 1971, when he was 17 and Howe's brother Vern, then the superintendent, hired him to help paint the dasher boards. He's at the Joe day and night, doing far more than driving the Zamboni and twirling octopuses. He sometimes sleeps on the sofa in his office, a cozy, homey hangout full of mementos. Osgood, a frequent visitor, autographed a ceiling tile.

Once a month, if the schedule allows, a player or the company gives Sobotka money to buy meat at Eastern Market -- sausage, burgers, ribs and chicken -- and Sobotka barbecues for the staff and the team at the gate where the trucks drive in. So much smoke wafted over the ice during practice one day, Bowman got upset. All was forgotten when the food was served.

Sobotka is married. He met his wife, Sandy, at the Olympia, but he said: "I spend more time here than I do at home. A couple of my guys say to me that I'm married to this place and to this job."

Stop into the press room, and Leslie Baker (36 years) serves you dinner. Baker started at the Joe in 1981, when she was 17 and got a job as a bus girl in the Olympia Club. She later started serving the press and the players, getting to know everybody. She has a bottle of Perrier and the TV remote waiting at Holland's reserved table in the press room before each game, so he can sip and watch hockey. When he finishes the Perrier, she brings him hot Earl Grey tea with one packet of honey. Like Holland said, it's home.

"I started out as the little sis to the players," Baker said. "And then I moved to the big sis. And then I turned to the aunt. And then I turned to the mother. And now I'm Grandma."

She laughed.

"It's a family," she said. "It really is."

Step into the elevator, and Eugene Sniezyk, a Purple Heart medal earned in the Korean War pinned to his lapel, pushes the buttons like he's at an old department store.

"Second floor! Lingerie!"

Walk into the press box, and Greg Barbaza (17 years) and Gary Hinds (26 years) greet you. Listen to the anthem, and "The Red Wings' own" Karen Newman (at least 26 years) sings. Listen closely, and you can still hear Budd Lynch (eternal). He spent 63 years with the Red Wings, most of it as a play-by-play and PA announcer. He died Oct. 9, 2012. But via a recording, he still announces, "Last minute of play in this period."

Now it's the last 60-65 minutes of play left in this building.

* * * * *

When the Red Wings have played at Joe Louis Arena this season, no one has booed the mention of Little Caesars Arena. Sadness is mixed with excitement this time.

"Everything about this place, I'm going to miss," Draper said. "I love it. The fans, amazing. Being down on the ice and looking up and seeing all the banners I was a part of, it's special. I'll never forget it."

But …

"It's time," Draper said.

Joe Louis Arena wasn't state of the art the day it opened. Little Caesars Arena will be spectacular and is part of a 50-block area named The District Detroit, a development project connecting midtown to downtown.

The capacity will be about the same as the Joe's, but the pitch of the new seats will be steep and gondola seating will hang over the lower bowl. No one should complain about being too far away and not being able to see. The fans will feel on top of the players. They will enjoy a new technology called cup holders too.

There will be a plaza with high-definition video boards. There will be offices, clubs, restaurants and shops in buildings surrounding the rink. There will be a glass roof over the area between the buildings and the rink, and that will be the concourse, full of natural light, spacious; quite a departure from the windowless, cramped Joe.

The players will have bigger and better facilities, plus an attached practice rink. The workers will have bigger and better spaces, including loading docks that don't let in as much cold winter air.

And the memories and the people will not be forgotten.

© Robert Laberge

There will be displays honoring the history of the Red Wings and the Detroit Pistons, who will move from the Palace of Auburn Hills in the suburbs. Most of the familiar faces will be there, doing the same jobs in the new place.

The goal will be to create a new history worth celebrating, so someday people feel the same way about Little Caesars Arena they did about the Olympia and the Joe.

"I think life's about making new memories," Babcock said, "and that's what the new building's going to be."