VANCOUVER -- The big day came Oct. 29. After years of fundraising and building, BC Children's Hospital opened the Teck Acute Care Centre.

Most people don't know this, not even at the hospital, but amid the hubbub, with no fanfare, Daniel Sedin was there.

Sedins' bond in Vancouver goes well beyond hockey

Connection to community through charitable endeavors left lasting impression

He and his twin brother, Henrik, had visited the hospital as members of the Vancouver Canucks. They had donated $1.5 million in 2010, inspiring others to donate millions more.

Now patients were moving into a $676 million, 640,000-square-foot facility billed as an innovative healing environment. Full of art and amenities, it was designed to comfort and calm, give families space to be together, and instill a sense of community.

"Daniel actually came," said Analyn Perez, a pediatric oncology nurse at the hospital for the past 20 years. "I remember hearing that he was coming and being able to connect with the families and say, 'Would you like to have a visit?' And they're like, 'Absolutely. This is amazing.'

"He did come around and visited basically every single patient that moved into this hospital, on his own."

Perhaps nothing better illustrates what Vancouver means to the Sedins and what the Sedins mean to Vancouver. They spent their entire NHL careers in this city, and for all they accomplished in their 17 seasons, they are hailed as better people than players.

The 37-year-old forwards announced their retirements Monday and will be celebrated Thursday when the Canucks play the Arizona Coyotes in their final home game (10 p.m. ET; SN360, SNE, SNO, SNP, FS-A PLUS, NHL.TV).

"It's leadership by example," said Don Lindsay, chair of the board of directors of the BC Children's Hospital Foundation. "They've done it on the ice. They've done it in the locker room. They've done it in the community. Again and again and again. This is bigger than the Art Ross Trophies, believe me."

* * * * *

The Sedins weren't beloved in the beginning. They didn't live up to expectations after the Canucks selected Daniel No. 2 and Henrik No. 3 in the 1999 NHL Draft, taking criticism in this passionate, sophisticated market.

In a press conference Monday, while talking about getting through those hard times, Daniel brought up how the Canucks were involved in the community and specifically mentioned visiting BC Children's Hospital.

"When you go there and see the kids, how happy they are, you meet their families, I think you realize that hockey is just a game," Daniel said. "I think that's probably the most emotional place that we got to, and I think as players we really appreciate that."

The Sedins blossomed later. Henrik won the Art Ross Trophy as scoring champion and the Hart Trophy as most valuable player in 2009-10. Daniel won the Art Ross and was runner-up for the Hart the following season.

At about that time, they approached the Canucks about donating to a cause that would touch people across British Columbia. In the wake of the financial crisis, the BC Children's Hospital Foundation had stalled about halfway to its goal of raising $200 million toward a new facility through the Campaign for BC's Children. The Sedins decided to donate the $1.5 million.

"I get choked up talking about it," Lindsay said. "I thought the decimal point was in the wrong place. This was such an extraordinary donation, totally initiated by them. We never even asked them.

"I've got to tell you: This doesn't happen. It doesn't happen, out of the blue, never been asked, no long-term cultivation of a relationship. People do not just come forward like that. Daniel and Henrik did."

There was one catch.

"They said they wanted it to be anonymous," Lindsay said. "They weren't out to get credit for it. They were just doing the right thing."

The Sedins had to be persuaded to allow their donation to become public, giving the campaign not just money but exposure. Lindsay talked about it on "Hockey Night in Canada."

Sure enough, their donation boosted donations.

"The big message for me is, by them being involved and showing what they do for others, I think they're motivating a lot of other people," said Kishore Mulpuri, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon at the hospital for the past 15 years. "They're true role models, because people follow their lives."

* * * * *

The Sedins visit the hospital a few times a year, sometimes officially with the Canucks and the media, sometimes unofficially with no one else around.

"I think they've become a little bit of an institution around here," Perez said. "It's not surprising whenever you see them here."

Like at the rink, they are the veterans. Like everywhere, they treat everyone the same.

"It's not always easy to walk into a patient room," Perez said. "These patients are sick. They have lots of tubes coming out of them. You see it especially with some of the young players. It's a bit nerve-wracking to walk in there.

"And so to watch players like Daniel and Henrik walk in there and just show [the young players] not to be afraid, just to kind of spend time just chatting with [the patients], whether it be about hockey or what their stay's been like, you just can't underestimate how powerful that is."

They take extra time, look the children in the eyes and speak to them as equals. They make them feel as normal as possible.

"The idea that you can actually meet your hero in person …" said Sand Northrup, a therapeutic clown at the hospital for the past 14 years, her voice trailing off. "Of course we struggle with hope around here, because some of the situations are very dire, and I sort of see [the Sedins] as an emblem of hope and possibility.

"They are the face of the Canucks in that way -- their kindness, their commitment, their dedication. So this is what they mean to the community. This is what they embody when they come and visit here. That's what I see."

* * * * *

On the seventh floor of the Teck Acute Care Centre is a Canucks playroom, thanks to a $1 million donation by the Canucks for Kids Fund. It has murals of Rogers Arena, TVs that mimic scoreboard screens, tickers displaying messages and an air-hockey table.

It is William Hodgkinson's favorite room in the hospital. It is around the corner from the hospital school, so on the days he's able to go to school, he comes for playtime before and after.

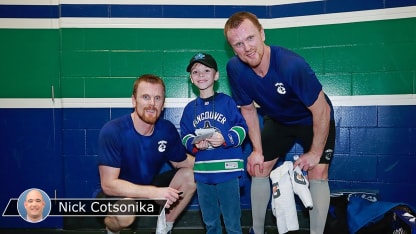

He's a 7-year-old from Penticton, British Columbia, who loves his hockey and has been here since Jan. 31, five hours from home, fighting a large tumor in his kidney and seven spots on his lungs. He has become friends with Canucks defenseman Erik Gudbranson, who has visited him a couple of times, and adores Henrik Sedin.

When the Canucks heard about him, they invited him to their game against the New York Islanders at Rogers Arena on March 5. He sat in Section 121, watched the Canucks win 4-3 in overtime and toured the locker room afterward.

"He was kind of standing outside the gym area, and Daniel Sedin walks up first," said Neeley Brimer, Hodgkinson's mother. "He just kind of was unable to speak. They chatted. And then Henrik walked out, and I actually thought he might faint.

"But it was amazing. They stood there. They talked to him, which I was kind of taken aback by, because it was postgame, and they were tired, and they were sweaty, and they had just spent a long time working out on the ice."

The Sedins took a picture with Hodgkinson. When he looked at it on his mother's phone in the Canucks playroom Wednesday, he broke into a big smile. He will be watching their last home game.

"The Sedins are retiring," he said. "I don't know how they got to be so good."