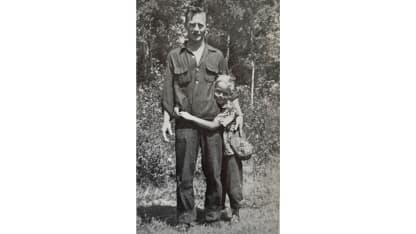

How did he help you develop your toughness as a hockey player?

"It started with a street hockey game when one of the bigger guys gave me the beating of my young life. He said, 'Next time make sure you beat him!' After that, I had my first hockey fight and got another licking. My father said, 'If you let a guy do that to you again, I won't talk to you.' So the next game I gave the guy a licking. My dad made a point of getting me accustomed to pain. When I was eight, a puck hit me right in the head and I was bleeding all over the place. My father gave me a once-over look and snapped, 'You're all right. Get back out there. The blood will dry. Shake it off.' He wound up later taking me to the hospital and I got three stitches. And when we got home he put them in a plastic box. All together dad saved every one of my first 100 stitches and pretty soon I became proud of them."

What else did he teach you?

"It wasn't just toughness; dad was a bug on scientific hockey. By the time I was seven he had me turning both ways on my skates, to the left and to the right. He would watch while I skated 50 times around the rink, stopping on both feet, then on one foot, then on one foot on both sides. He also had me watch his favorite player, Ted Kennedy of the Maple Leafs. Kennedy didn't skate that well but he was inspiring and worked for everything he got. Kennedy was especially good at face-offs so dad had me focus on Kennedy's technique on the draws and I got good at it"

How good?

"There's no question in my mind, that with all my dad taught me and my focusing on Ted Kennedy, that I became the best face-off man in the NHL. And I know that it didn't come by accident. It was my father teaching me to study Kennedy's special moves. I copied the way Ted positioned his feet, his hands and his weight, and I carefully studied his timing. By the time I got to the Bruins, I had reached a point where I expected to win -- without too much trouble -- about 90 percent of the face-offs. And if you ask me the other face-off secret of mine, it was concentration."

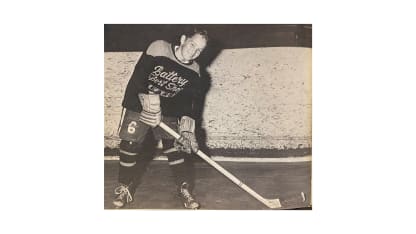

What do you remember about your first organized league game?

"I was eight, in a Peewee Division for kids between eight and 10 and we played in Niagara Falls Memorial Arena, starting at six in the morning. Mr. Gould, the father of one of my teammates, said he'd give me a dollar for every goal I scored and fifty cents for an assist. I wound up with nine assists for the year so he didn't have too much to worry about. Still, because I never scored, I felt like a real bum hockey player. But that didn't seem to bother my dad. 'Don't worry, kid,' he'd say, 'you're a great playmaker. The coach just doesn't appreciate you.'"

When did the goals start to come?

"The next year we played a 20-game schedule. I got nine goals and 15 assists and we won the championship. The year after that it was 10 goals and 15 assists and I was making a few bucks from Mr. Gould. The following year I scored 44 goals and about 60 assists. Finally, my dad convinced me to call off the bet. 'You're too big for that. You don't need the money now.' By the way, I didn't like my father's thinking on that subject one bit."