Ward, who had gone to the camp, soon became an instructor at it for Weekes. Ward joined as a consulting coach. Among those who'd attend were Simmonds and Chris Stewart.

"You'd see these guys who looked like us, who came from the same place as us, who were playing in the NHL, and here we were on the ice with them," said Chris Stewart, 34. "It made the dream seem more reachable."

And realistic.

"It was great incentive," Simmonds said. "It helped open doors even wider for some of us who actually made the League."

* * * *

Scarborough, which has a population of 630,000, was a popular landing spot for European immigrants starting in the 1950s. By the late 1970s, an influx of Asian and Caribbean families had started making it a desired place to live for different cultures.

"It's a melting pot," Weekes said. "The good part is that there are so many people from so many backgrounds in Scarborough. You want to succeed. And there's an edge to being from there, a toughness about you, a realness.

"Even though we have a lot of nice areas in Scarborough, it's not powder puff."

The East Side Motel on Kingston Road certainly wasn't, as the Stewarts can attest.

The brothers lived there from 1996-2000 in Room 29 with their parents and five sisters. Toronto's shelter spaces for underprivileged families were overflowing at the time, and the city turned to motels like the East Side, which charged by the hour, the day or the week.

"I'm still scared of rodents to this day," said Anthony Stewart, recalling the mice scampering around the room. "I mean, it's the type of place that gave you the incentive to do anything possible to get out of there and fight to be successful in life.

"There were hookers in some of the other rooms. Drug addicts were all around. There were stabbings and other crimes. You fought to get out of there."

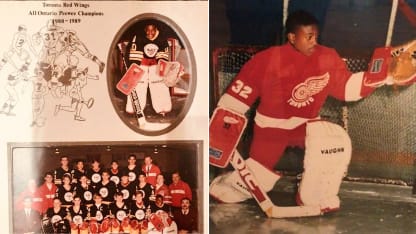

The brothers realized sports could be a way out. Their dad, Norman, would scrape together used hockey equipment for Anthony, who'd pass it down to Chris, three years his junior. They'd make the 2-mile walk to the local rink through blizzards and rain, whatever it took to play. So after Anthony was selected by the Panthers in the first round (No. 25) of the 2003 NHL Draft, one of the first things he did with his $800,000 signing bonus was buy his family a new home.

Motivated by the struggles of childhood, the Stewarts, like many of the Black Scarborough players of today and yesterday, are trying to use their public platforms to help bring change and make the game available to everyone.

In 2014, Anthony established Stewart Hockey, a series of camps and clinics run with Chris with the goal of creating an environment where players of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds can advance their hockey skills. In 2020, Chris became a co-owner of Minnesota Hockey Camps, the brainchild of Herb Brooks, coach of the United States men's hockey team at the 1980 Lake Placid Olympics, in 1976.

Chris also joined Simmonds and Ward as founding members of the Hockey Diversity Alliance 19 months ago, joining past and present NHL players Evander Kane, Akim Aliu, Trevor Daley and Mathew Dumba. Simmonds said the concept of the group, which aims to eradicate racism and intolerance in hockey, was long overdue.

"People talk about bringing change to the game, but racism remains significant in it," Simmonds said. "Talk is talk. We need actions. And not just from us."

Weekes and Carter are part of the NHL Executive Inclusion Council, comprised of owners, team presidents, general managers and retired and current players. It is geared toward ensuring diversity and inclusion within NHL organizations.

"We all know that if the owners aren't on board, the Commissioner is not on board, the National Hockey League Players' Association isn't on board, then nothing is going to happen," Carter said. "Instead, it's the opposite. And it's great to see so many pulling on the rope in the right direction."

For Weekes, Carter and Anthony Stewart, their voices and push for change are magnified by their roles as national broadcasters.

Weekes became the first Black former player to be a hockey analyst on national television when he joined "Hockey Night in Canada" in 2009. Carter joined NBC Sports in 2013 as an analyst and has continued in that role for TNT this season. Anthony Stewart is an analyst on "Hockey Night in Canada" and midweek games on Rogers Sportsnet.

"This goes beyond playing hockey," Stewart said. "This is about showing kids of all ethnicities that they can be whatever they want: hockey players, broadcasters, whatever their dreams are."