"A puck last game that sailed in under the goalie's arm is a bit of a blur, a streak, then it lands in the net," said Gordon, known as "Flash" by anyone who works with him. "Tonight, the same shot, if you have a clear view of it, you're going to be able to read that puck as it flutters into the net. You could almost literally read the logo on the puck and almost be able to read the edge of it to see where it was made."

The super-mo system, used in Stanley Cup Final games in Las Vegas last season, is much more complex than the standard. Two streams of video are fed from transmitters, one a live feed to which a TV director can cut at any time, the other a replay-triggered stream that can be used at the frame rate of a director's discretion to replay an event of choice -- a goal, save, deflection or goal-mouth collision.

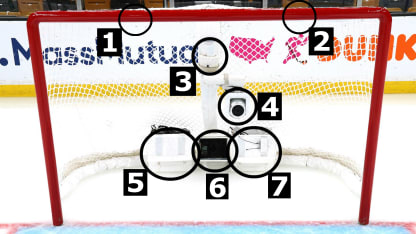

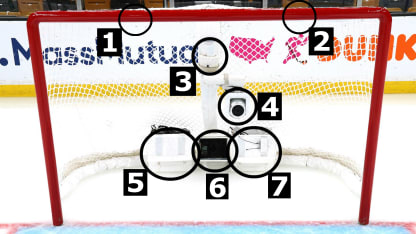

Gordon, a native of Oakville, Ontario, has been a specialty-camera technician and operator for about 25 years, trained to operate cameras mounted under the scoreboard and over the glass. In Boston, he was responsible for the cameras in each net, as he will be throughout the series. The feed from the nets is provided to NBC/NBCSN, CBC, Sportsnet and his employer in this Final, TVA Sports.

Game 3 is at Enterprise Center in St. Louis on Saturday (8 p.m. ET; NBCSN, CBC, SN, TVAS).