When you think about the word "soul," you think about going underneath the surface -- trying to capture something that's always been there, something you can feel, but something no one's ever really seen. In hockey, the Black athlete has often been the soul you never see. Black athletes have shaped hockey from the very beginning, from the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes in the 1890s to the Black superstars in the NHL today.

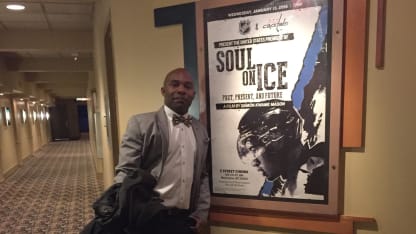

'Soul on Ice' celebrates fifth anniversary

Director Mason on film that documents past, present, future of Black experience in hockey

By

Kwame Damon Mason / Special to NHL.com

Five years ago, I released "Soul on Ice: Past, Present, and Future," to document the Black experience in hockey -- highlighting Black players' stories and contributions -- because I know how powerful it is for that soul to be celebrated, seen, and understood.

As the son of Guyanese immigrants who came to Canada in the late 1960s, I felt the game's soul before I understood it. When I was 10, my brother was invited to play youth hockey with the Toronto Aeros. My dad -- who watched "Hockey Night in Canada" like everyone else in the country - thought hockey was a good way for kids to stay active. So, he took my brother to get fitted for gear.

I remember sitting in the storage unit of Fenside Arena, watching my brother try on secondhand shoulder pads and thinking he looked like a superhero. Then I started going to his games, and it wasn't long before I thought, "Man, I want to do this, too."

When I finally said it out loud -- "Dad, next year, I want to play" - he took me to the store to get my own superhero gear.

I'll never forget the smell of those elbow pads and gloves - a smell that said, "This is fresh, this is sick, this is mine." And I'll never forget my dad saying, "Go do your homework. Go to bed. What are you doing?" when I didn't take my equipment off for three hours. I was walking around the house in my skates, taping up my stick, feeling too excited about becoming a hockey player to focus on anything else.

But after playing for just two years, I put my gear away for good -- because I couldn't find enough connections to the game.

Despite my dad's support, there were things he couldn't help me navigate. Like most immigrants from the West Indies, he knew much more about soccer than he did about hockey -- because soccer is what he grew up with. He couldn't teach me about the next steps beyond house league or the blueprint to figure out hockey culture. And there weren't many people reaching out to help new faces in the sport.

At the same time, my friend group was changing. In elementary school, when I first started playing hockey, most of my friends were white. When I got to junior high school in the early 1980s, things were different -- "Rapper's Delight" was introducing rap music to the world and breakdancing emerged on the scene. There was a real cultural moment for people who looked like me, and I found myself hanging out with a new group of friends who also looked like me. If they were talking about sports, they were talking about basketball and football, not hockey. And if anyone, of any race, was talking about Black kids in hockey, they were usually talking about the stereotypes: "Black people have weak ankles" or "It's a white boy sport, anyway."

So I walked away from the game. Stopped following it too.

I didn't come back until 20 years later -- when I saw Jarome Iginla on the ice.

It was 2002, and I'd just gotten a radio job in Calgary. My new boss welcomed me to the crew with tickets to a Flames game. It's my first game at an NHL arena, we're sitting in some nice corporate seats and suddenly I see this guy jump on the ice and start doing his thing.

I turn to my boss with three questions: "Who's THAT guy? Is that a Black guy? And he's your captain?!"

He has three answers: "Jarome Iginla. Yes. And yes."

That's all it took.

When I saw this guy who looks like me (well, looks a little lighter, but still looks like me), I remembered instantly why I loved this sport. And I loved it even more because there was a Black guy out there, and he was killing it -- scoring, fighting and leading his team. I didn't care if the stereotypes said I should stay away. I didn't care if some of my Black friends didn't get it. I was back to loving the game, and I was going to talk hockey anyway.

The more I got back into hockey, the more I thought about what lies below its surface. The athleticism in hockey matches the athleticism we see in all the great Black athletes in other sports. What if LeBron James' or Michael Jordan's parents had put them in hockey? If you transitioned their skills to the ice, those guys would've been amazing. Why didn't the hockey community celebrate its past Black athletes to make them role models for the future? What could up-and-coming Black stars (at the time, P.K. Subban, Wayne Simmonds and other skilled role players) tell us about the game in the present?

I knew I wanted to explore these questions. I wanted to make a documentary. I had no filmmaking experience -- I was just a film nerd with a radio job and no money for a film project -- but I had the motivation to try.

That motivation came from my mother.

In 2011, my mom was diagnosed with cancer. She would pass away within a month of being diagnosed, and she seemed to know that she didn't have much time. I realized this when I was sitting on her hospital bed, and she looked at me and said, "What are you going to do?" in a way that expressed every worry, concern, and hope that a mother has for her kid's future. I mentioned that I was holding onto this crazy documentary idea. I don't know what I expected my mom to say; she'd always encouraged me to find jobs that offered security, fitting the mindset of many West Indian immigrant parents who want their children to have stable careers to avoid struggles like the ones they had to go through. But my mom didn't hesitate before saying, "Do it. Go for it. That sounds like a great idea."

So I had my check mark to go.

Somehow, exactly one year to the day after my mom passed, I was conducting my first interview for "Soul on Ice." Cameras and lights had been set up in a nursing home in North York, where I went to interview Black hockey legend Herb Carnegie.

He was 92 years old, and he looked frail.

But in my mind? He looked like a superhero.

I could see him in his prime -- the fast, skilled, tough player who dominated the Quebec Provincial League in the 1940s. The trailblazer who earned a tryout with the New York Rangers in 1948. The role model who turned down the Rangers' contract offer because he knew they were offering him less than what he was worth -- and he knew it had something to do with his race.

This was the guy who Jean Béliveau, Willie O'Ree, and all the great hockey players said was one of the best during his time. And although the man in front of me was suffering from dementia, he could recall almost every memory when I asked him questions about the game. He remembered exactly what it felt like to play and exactly how much it hurt him when racism blocked his path to the NHL.

As we wrapped up the interview, I had to tell him how much it meant to me. "I'm going to make you proud," I said. "I'm going to make this film, and we're going to get this story out there." He smiled and held my hand, and I told him I'd come back and visit -- just to be near him and offer company.

I never got the chance. A week and a half later, he was gone.

From that day forward, I knew that nothing would stop me from making this film. I made this man a promise, and I was going to tell his story -- tell all of our stories in this beautiful game.

I put a picture of me and Herb as my screensaver, and that served as my motivation for three years. Any time I would get frustrated, any time people would cancel interviews, any time I would get rejected for film grants, any time bill collectors would call me, any time I wasn't sure if I'd made the right call in selling my condo and moving back home to finance this film, any time I didn't know how I'd eat the next day because I had no real income … I would just look at Herb Carnegie. I knew I had to keep going, and one day there'd be a moment to explain why all these forces kept pushing me to tell these stories.

The moment came on Oct. 7, 2015, at the world premiere of "Soul on Ice" at the Edmonton International Film Festival.

It was a sold-out showing, helped by legendary Edmonton Oilers goalie Grant Fuhr, the first Black player inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame, who appeared in the film and rearranged his schedule to attend the premiere. Grant brought a lot of attention to the step and repeat banner. I brought the gift of gab from my radio days, plus the fresh new suit I forced myself to buy the week before. The audience brought excitement as the lights started to dim and everyone took their seats before the film began. I could tell things were going well when everyone laughed where I wanted them to laugh and teared up where I wanted them to cry.

And when the lights came back up, everyone was standing. And clapping.

For "Soul on Ice."

This film, created against all odds, had found a way to move people by expressing what it means to be Black in hockey. The audience's ovation left me crying. That's when I really allowed myself to wonder, "What's next? How far can this film go?"

It didn't take long before the NHL helped answer that question.

I'd heard that the NHL wanted to see my film -- I've never been sure how they found out about it. I sent a copy for the League to review, and it took less than a day before I got their response: "Soul on Ice" was something the League wanted to share. They wanted to promote and amplify it, so more people would understand the soul beneath the surface of the game.

From January 2016 until today, the NHL and its clubs have hosted dozens of "Soul on Ice" screenings, and I've traveled to NHL markets across North America to talk about Black hockey history in the past, present, and future.

The "future" part has been on my mind recently. As the racial justice movement grows and hockey players speak out for change, I've heard a lot of people talk about how hockey needs more diversity. It does, of course. The game needs more Black kids, more Indigenous kids and more kids of color. We need to get kids from different backgrounds on the ice.

But at the same time, hockey has always had diversity. There has never been a time when Black people didn't play hockey. The Colored Hockey League gave us an official home in the 1890s. Herb Carnegie, his brother Ossie, and Manny McIntyre became the first all-Black line in professional hockey in the 1940s. Willie O'Ree broke through to the NHL in 1958, and more than 100 Black NHLers have followed. For decades, hockey has been played in Newark and Harlem, and today it is also played in Kenya and Jamaica.

So diversity -- though we need more of it -- is not the biggest hurdle for the hockey community. What hockey really needs is inclusion. We need an environment that embraces and celebrates Black culture.

We need Black executives and GMs committed to telling Black stories. We need Black kids to see themselves in Black players and believe that every piece of who they are is wanted and welcomed in this game.

We will get there. The pieces for progress are already in place. There are leaders all over the hockey ecosystem. They will become the new superheroes. It's just a matter of putting everything together.

I'm optimistic about this game's future because I know there is a movement underway. It's not always in the public eye. You can't always see it, and you can't always understand it. But if you pay attention to the soul of the game, you can feel it.

You can always feel what matters in your soul.