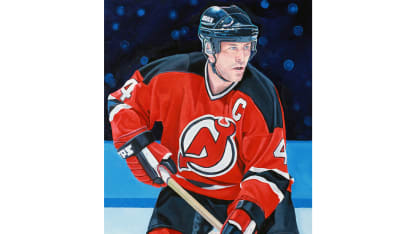

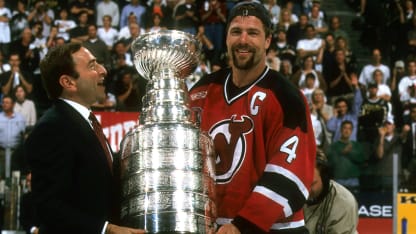

Although he was the Devils captain, Stevens was a man of few words. He did most of his talking through the way he competed in games and practices.

MacLean said Stevens was "a very quiet, very reserved guy" off the ice.

"But he'd put the skates on and he was battle-ready whether it was practice or a game," MacLean said. "That, to me, was his leadership, how he competed in games, in practices. He knew you can get better practicing against better players. And he was the guy. He set the tone. We knew we had to battle when we were in there with him. There was no letup. Whether that was a 30-minute, 40-minute or an hour practice, that's what you were going to get."

If a teammate didn't practice as hard as Stevens, the captain was sure to let him know his effort wasn't good enough.

"Well, I think I got their attention," Stevens said. "You can make each other accountable. I really believed that practice was a big part of winning hockey games and we practiced hard. We had our scuffles. We had other guys who practiced hard.

"That's a big part of having success."

For more, see all 100 Greatest Players