Brodeur fondly recalls father's iconic photo from 1972 Summit Series

Hall of Famer has never seen video of Henderson goal, dad's picture 'all I need'

Not one time, he says. Ever.

One of the greatest goalies of all time has not seen one of the most famous goals scored in Canadian hockey history.

"I don't remember seeing Henderson's goal on TV or on YouTube or anywhere else, and I've never searched for it," Brodeur said, speaking during the 50th anniversary month of the landmark eight-game series between a team of NHL stars and one from the former Soviet Union.

There's an explanation for this.

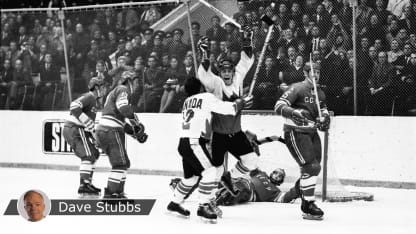

The Hall of Fame goalie's late father, Denis, was one of two men who on Sept. 28, 1972 photographed an iconic image of Team Canada's Yvan Cournoyer bear-hugging Henderson a split second after the latter had scored his third consecutive game-winning goal.

Toronto Star staff photographer Frank Lennon was sitting shoulder to shoulder with Brodeur at ice level in Moscow's Luzhniki Palace of Sports when Henderson scored the goal that tilted the hockey planet off its axis.

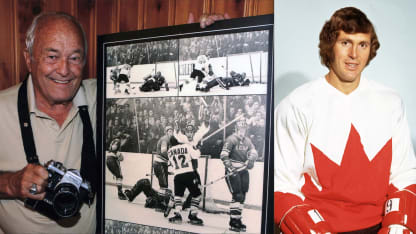

Denis Brodeur with a few of his photos from the sequence of the Game 8-winning goal scored by Paul Henderson (right). Denis Brodeur Collection; Hockey Hall of Fame

Lennon's image, syndicated to the Canadian Press news agency, appeared on the front page of the Star and newspapers across Canada the next morning.

The photo taken by Denis Brodeur, who was in Moscow freelancing for a handful of clients and a book project, is almost a mirror image.

In fact, Brodeur's photo is so close to the frame of Lennon, which won the 1972 National Newspaper Award for spot news photography, that sometimes even the photographers needed a double-take to identify the shooter.

Martin Brodeur was not quite five months old when his father took the greatest photo of his storied career as a Montreal-based sports photographer.

"I've never thought about looking for video of the goal," Brodeur says today. "It's clear to me as a photograph that's been in front of me since I was born. It's all I've seen."

That he played his entire NHL career in the United States and lives there today might play a role in this extraordinary fact, and yet …

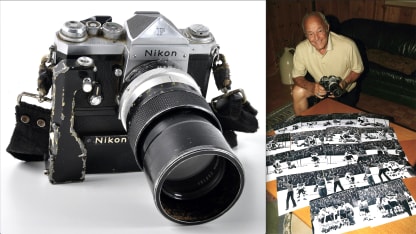

The camera Denis Brodeur used to shoot his historic photo and posing with a series of prints from the climactic Game 8 sequence. Courtesy Classic Auctions

"Mr. Henderson signed a copy of my dad's photo that I have in my office, but I've never seen video of it," Brodeur said. "For me, I'm happy that it's engrained in my mind as the photo, seeing Henderson and Cournoyer celebrating, the Russians with their heads down."

Usually published in a tightly cropped vertical of the hug, the photo says so much more when seen in its original wide-horizontal form.

At left are defenseman Valeri Vasiliev and center Vladimir Shadrin, helplessly frozen in almost identical body position. Goalie Vladislav Tretiak is lying flat, his right leg bent at the knee, his skate dug into the ice as he seemingly watches the two celebrating Canadians; at right is defenseman Yuri Liapkin, his stick in front of his face.

Denis Brodeur's monumental photo was his crowning glory in a lifetime of hockey involvement.

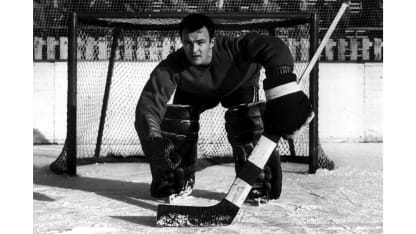

He had preceded Martin onto Olympic ice, winning a bronze medal in 1956 as a goalie representing Canada on the Kitchener-Waterloo Dutchmen in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy.

Denis Brodeur representing Canada in the 1956 Olympics in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy. Denis Brodeur Collection

Brodeur played junior, senior and minor-pro hockey before and after the Olympics, including a season in Victoriaville, Quebec, in the late 1940s with future Canadiens icon Jean Beliveau.

He took up photography at Montreal's Immaculate Conception Sports Centre in the late 1950s, peddling his publicity shots to newspapers around town and crime shots to the city's spicy tabloids.

In the early 1960s, Montreal-Matin sports editor Jacques Beauchamp hired him as a regular freelancer. Brodeur shot his first Montreal Canadiens game at the Forum in 1962, balancing and focusing his boxy Roliflex camera with one hand, lifting his flash above the glass with the other. If he did well, Beauchamp would pay him $3 for a photo.

Eventually, hired as the Canadiens' team photographer, Brodeur installed remote-triggered strobe flashes in the Forum rafters, investing $1,500 in a system that brilliantly lit his exquisitely detailed images from the 1969-70 season until the arena's closing March 11, 1996.

© Getty Images

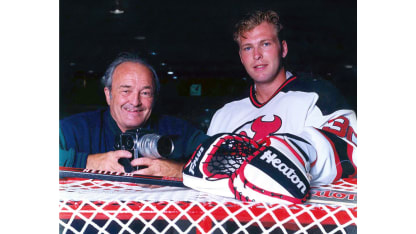

Denis Brodeur with his son, Martin, at the 1990 NHL Draft in Vancouver. Martin had just been selected in the first round (No. 20) by the New Jersey Devils. Bruce Bennett, Getty Images

His prodigious body of work -- more than a million negatives -- was remarkable given that for most of his career he was shooting 2¼-inch negatives, not 35-millimeter film through motor-driven camera bodies or the digital format he would finally embrace.

With his trusty Hasselblad, for decades Brodeur would shoot a single frame, then wait seven seconds for his Forum strobes to recycle, young Martin often his assistant in the Canadiens portrait studio.

Brodeur covered any event worth his film in Montreal, including Expo 67, the 1976 Olympics, the Canadiens and baseball's Expos as their official photographer, soccer, Formula 1 racing, football, golf and pro wrestling while also doing corporate work.

He published a handful of books before his death in 2013 at age 82; they included one on Martin, whom he shot from road hockey as a boy throughout his NHL career and gold-medal victories for Canada at the 2002 Salt Lake City and 2010 Vancouver Olympics.

© Dave Stubbs

Denis and Martin Brodeur, taken in the late 1990s. Courtesy Denis Brodeur Jr.

The bulk of Brodeur's hockey work was purchased by the NHL in 2006, though the family kept everything he shot of Martin as well as the Nikon camera body and the sequence of 17 negatives he shot to capture Henderson's historic goal in Moscow.

Brodeur shot about 3,000 frames during his 1972 trip to Moscow.

"I could never beat this," he said in 2012, almost exactly a year before his death. "I've taken photos of Martin with his Stanley Cups (1995, 2000, 2003), his Vezina trophies (2003, 2004, 2007, 2008) and his Olympic gold medals, but I'll never do better than my picture of Henderson."

Brodeur was in Moscow on his own ticket, freelancing for maybe a half-dozen clients while shooting for a commemorative book to be published within days of the series finale.

He even was taking woman-in-the-street photos for Team Canada assistant coach John Ferguson, who would use those images for some of his work back home in the fashion trade.

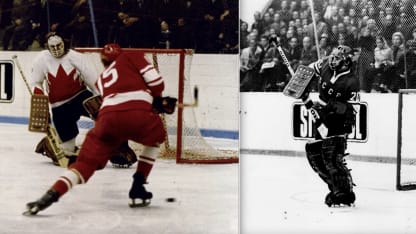

Team Canada center Phil Esposito (7) and forward Yvan Cournoyer battle in close with Soviet defenseman Valeri Vasiliev and goalie Vladislav Tretiak. Denis Brodeur Collection

Brodeur, whose day job included shooting action photos for Canadiens programs, covered Games 1 and 2 of the series in Montreal and Toronto. Yet he wasn't even certain he'd get to Moscow, terribly ill with bleeding in his intestines just before departure. He was a nervous wreck, warned by many that the repressive Soviets likely wouldn't let him return home with his film.

So Brodeur packed chocolate bars, lots of them, to use as calling cards and timely gifts. He connected with a Luzhniki usher, who gave him preferred places to shoot in exchange for a treat, and he grew friendly with a photographer from the newspaper Izvestia, who developed the visitor's film in the newsroom's darkroom in exchange for stories about Ken Dryden and tips on Brodeur's photo techniques.

It was early in the third period of Game 8 when it occurred to Brodeur that he'd not yet photographed Soviet coach Vsevolod Bobrov. So he left his rinkside spot and went to the other side of the arena, where he was when Phil Esposito pulled Canada to within a goal 2:27 into the period.

"I suddenly thought that Canada might tie," Brodeur said, "so I rushed back to my previous spot. The usher had waved me through, so the chocolate paid off."

Alexander Yakushev fans on a shot attempt on Team Canada goalie Ken Dryden, with Vladislav Tretiak in action for the Soviets. Denis Brodeur Collection

Ten minutes later, Cournoyer indeed tied the game at 5-5. And with 34 seconds remaining, Henderson buried his historic winner.

Brodeur's 35mm Nikon F, a sturdy camera a few years old, was pressed to his eye, and through the viewfinder he saw nothing with its shutter depressed, the motor-drive firing roughly three frames per second.

He was using fast black-and-white Kodak film that he pushed to its maximum to compensate for poor arena light, shooting 1/500th of a second with his 135mm lens wide open, its f/2.8 aperture yielding virtually no depth of field.

There was zero forgiveness with his focus at this setting; he'd be sharp or the images would be junk. And long before digital photography afforded instant review, Brodeur would know nothing until his film was dipped into developing chemicals at Izvestia nearly an hour later, he and his Soviet photo friend driven there postgame by a waiting chauffeur.

"I thought I had the shot," Brodeur said. "But my fear was that the best photo was not taken at all, during the instants the motor drive advanced the film."

At Izvestia, he watched his ghostly images darken to life through the developing soup, his heart beating again.

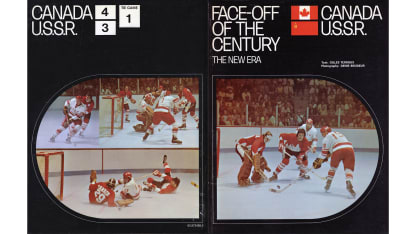

The 1972 book by Gilles Terroux and Denis Brodeur on the historic Summit Series. Courtesy Collier-Macmillan Canada

Seventeen grainy but tack-sharp images emerged, the final two of Team Canada's post-goal celebration numbered 37 and 38 -- the only time in Brodeur's career that he shot a roll with more than 36 frames wound onto it.

"I showed the pictures to Gilles (Terroux, co-author of their book), but I don't think at the time I realized how good they were," he said.

"So many things could have gone wrong to ruin the sequence, but everything went A-1."

Their 96-page book, "Face-Off of the Century: The New Era," was produced so quickly that a goal photo from the sequence appears only on Page 73 -- as a vertical -- under the caption, "The Russians can't believe their eyes."

Brodeur protected the negatives for decades, even packing them on trips and family vacations. They remain in superb condition to this day, in safekeeping with one of Martin's friends.

"They went everywhere with me," Denis Brodeur said. "I was afraid of them being lost if the house caught fire. And now I wonder, what if my car had been stolen? It's crazy."

In time, Martin would meet the three goalies who played in the Summit Series.

"I met Tony Esposito a bunch of times in Chicago when he was still around the team," he said of the Blackhawks' late star and ambassador.

"The first time I met Ken Dryden was at a dinner of the Canadian Society (now Association) of New York. I was so excited, I'd never had a chance to meet Ken in Montreal. Playing in the NHL (with the New Jersey Devils), they invited me. To me, he was somewhat of an idol, with Patrick Roy. But through my dad, Ken Dryden was the ultimate."

Martin Brodeur as an assistant coach with Vladislav Tretiak in 1989 at the latter's goaltending school on the south shore of Montreal; Tretiak in action with his Central Red Army team in a 3-3 tie against the Canadiens at the Montreal Forum on New Year's Eve 1975. Courtesy Martin Brodeur; Denis Brodeur, Getty Images

By then, Brodeur was closer to Tretiak than he was to either of the goalies from Canada. Tretiak had operated a goaltending school on Montreal's south shore in the late 1980s and early '90s, Denis Brodeur naturally the school's photographer. Martin attended the school, his first, in 1989 at age 17, then worked alongside Tretiak as a coach the following year and for a couple more after he'd been selected by the Devils in the first round (No. 20, Tretiak's sweater number) of the 1990 NHL Draft.

"Tretiak was at my Hall of Fame induction (in 2018), there for Alexander Yakushev's induction," Brodeur said. "He came over and talked to me that night about our history. He's one of the favorite people I've ever met. I learned so much about goaltending through him, in attitude and work ethic through the hockey school and teaching with him."

Brodeur has never told Tretiak that he has not seen in video form what surely is the most famous goal ever scored against him; goalies are much more likely to discuss great saves.

Martin and Denis Brodeur with his 2002 Salt Lake City Olympic gold medal and his father, Denis, with the bronze he won for Canada in 1956 in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy; and father and son after Martin Brodeur's 551st regular-season win, recorded at Montreal's Bell Centre on March 14, 2009. The win tied Brodeur with Patrick Roy for the NHL lead. Courtesy Denis Brodeur Jr.; Andre Ringuette, NHLI via Getty Images

Nor has Martin had occasion to speak with Henderson about how his father and a Canadian hockey hero are intrinsically linked, even if a shooter of film and a shooter of pucks never shook hands.

If Martin has never seen video of The Goal, as it's referred to in Canada, a proper noun, nor was Denis close to Henderson. The elder Brodeur seemed to think he'd met the subject of his most famous photo maybe once, their paths simply not crossing through the decades.

"There have been a few times that Paul and I were invited to the same function, but it's never worked out," Denis Brodeur said in 2012. "And that's too bad, because I'd have enjoyed talking to him."

Fifty years later, Martin Brodeur is again looking at a photo that literally defines his father's life.

"For our family, my dad's photography consumed us. That's what he did for so many years," he said. "Talk about so many photos that he took over 50 years and it comes down to that single picture in Moscow. One click. That's all I need to see."

Main photo of Paul Henderson Game 8 celebration courtesy Martin Brodeur, Denis Brodeur Collection