Jiggs McDonald was being put to the test, and it had nothing to do with his considerable hockey play-by-play announcing skills.

Could he come in under budget for training camp? Or, more precisely, could he escape the wrath of Los Angeles Kings owner Jack Kent Cooke?

Looking back at Kings' quirky beginnings

Expansion team held memorable first training camp 50 years ago

By

Lisa Dillman @reallisa / NHL.com Staff Writer

Well … no.

There were 77 players due to arrive in Guelph, Ontario, for the first Los Angeles Kings training camp, starting Sept. 6, 1967. The NHL had doubled in size from six teams to 12, creating unprecedented opportunities, and some of the expansion teams decided to train in Ontario.

So McDonald, the advance man, was tasked with finding food and shelter for the players with the limit of $9 per player, per day. That was in Canadian currency. "And the Canuck buck was worth more than the U.S. dollar in 1967," McDonald said.

With $5 per day allotted for the hotel, he didn't have much wiggle room for the meals but came close to meeting the $9 ceiling. He searched all over Guelph for a dinner spot and eventually found a restaurant outside of town at a golf course, which, after some hard bargaining, agreed to charge $2.25 per player, per dinner.

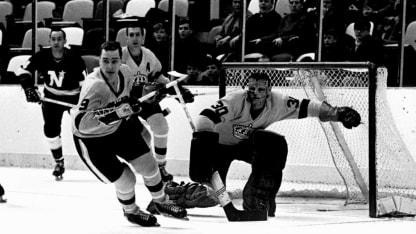

© B Bennett/Getty Images

That pushed the total figure to 25 cents past Cooke's maximum per day.

"Mr. Cooke was upset with me," McDonald said. "He had come back from England and his words to me were that I obviously had no concept of mathematics. He said, 'How many players in camp do we have?' I said, 'We have 77.' He said, 'How many days of the week? That's an astronomical sum of money you've cost me.'"

Cooke had paid $2 million so the Kings could join the NHL. On the day he was awarded the Kings (Feb. 9, 1966), he told Canada's national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, "I feel like I've just been elected the king of England!"

By the time the Kings assembled in Guelph, known as the Royal City, Cooke was feeling decidedly less regal. He was annoyed by the cost "overrun" on meals and unhappy that the community hadn't yet put any signage up to welcome the Kings. Somehow, McDonald found a way to get it all done.

Indeed, NHL expansion was organized chaos.

Among those at that first Kings camp was future Hall of Fame goaltender Terry Sawchuk. Sawchuk was one of two players allowed to have a car in training camp and made extra money by charging his teammates to get to dinner outside of town at the golf course, McDonald said.

The most decorated individual was Red Kelly, who had won four Stanley Cup championships with the Detroit Red Wings and four more with the Toronto Maple Leafs as a defenseman, winning his final title with the Maple Leafs on May 2, 1967.

But he was coaching the Kings, not playing for them.

Defenseman Bob Wall, the first Kings captain, found out Los Angeles had claimed him in the 1967 expansion draft by reading it in the Toronto Star. A few months later, he was testing his skating skills in camp against Kelly.

"Some of the guys couldn't skate backward very well and Red was a very good skater, an excellent skater," Wall said of the then-40-year-old.

"I would challenge him. I was very agile … we used to race."

Kelly could easily handle that, a more welcome challenge than the curveball that Cooke tossed at the new coach at training camp.

"He wanted Red Kelly to introduce him to each player, individually," said McDonald, who called Kings games from 1967-72 and did one of their games last season, filling in for Bob Miller. "Red hadn't seen any of these guys until the day before camp. He may have known five guys by name, and now you've got 72 others.

"So each guy had to give Red the name of the guy coming behind him. We pulled it off."

Cooke tried to cut corners in other creative ways. Wall remembered when a chewing-gum card company came in to take pictures during camp.

"The first year the company came in to take pictures of all the guys and if you look back now, all those cards that were taken that year, all those pictures that were taken, every guy is wearing No. 18," Wall said.

Wall said he had asked for his usual No. 2 but was told that Cooke didn't want to get all the sweaters dirty.

"So just the one sweater," Wall said. "Every guy had to wear No. 18. Is that crazy, or what?"

Larry Regan was the general manager and, like Kelly, new at his position. The organization immediately named Wall captain, and he negotiated a three-year contract with Regan.

"We had no agents in those days," said Wall, who owns Tim Hortons restaurants in Ontario. "You had to negotiate yourself. And, quote, $18,000 for the first year, $21,000 for the second and $23,000 for the third.

"I was happy. I was really happy. That meant I didn't have to work in the summer and my wife didn't have to work."

Wall's second child, a son named Dan, was born during training camp in Guelph, and Regan played a crucial role in getting Wall to the hospital.

"All the guys had gone out for a couple of beers," Wall said. "I get a phone call, 'Your wife has gone to the hospital.' Larry said, 'You've had a couple of beers, I'll drive you.' I had my car and it (the hospital) wasn't even an hour away. He (Regan) drove me to the hospital and took my car back to Guelph."

It may have all started for the Kings in Guelph, but their impact was fleeting in the community. By the next training camp, they were in Barrie, Ontario.

Sawchuk, who played 36 games for the Kings in their first season, was gone, having been traded to the Red Wings.

Not to be forgotten from the earliest days was the foundation of another Cooke mandate: Nicknames.

There were Bill "Cowboy" Flett and Eddie "The Jet" Joyal, to name a couple. Even McDonald, born John Kenneth McDonald, couldn't escape Cooke's edict.

McDonald had used Ken as an adult. But that wasn't good enough for Cooke. He asked to meet with McDonald during training camp.

"John Kenneth McDonald is as fine a name as I've ever heard," McDonald said, quoting Cooke. "He said, 'It just rolls off your tongue, 'Ken McDonald.' But it goes in one ear and out the other.'

"We tried Scotty. I forget how many different nicknames we tried. Finally he pounded his fist on the desk in frustration: 'You've had a nickname. I've had a nickname.'"

He demanded to know what McDonald's nickname had been as a child.

"I very quietly said, 'Jiggs,'" McDonald said. "He said, 'Speak up, I can't hear you.' I said, 'Jiggs.'

"He said. 'Jiggs McDonald, marvelous. We'll use it.'"