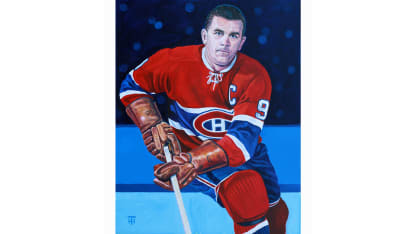

As part of the NHL Centennial Celebration, renowned Canadian artist Tony Harris will paint original portraits of each of the 100 Greatest NHL Players presented by Molson Canadian as chosen by a Blue Ribbon panel. NHL.com is unveiling two portraits each day this week.

Today, the portraits of center Jean Beliveau and forward Maurice Richard are unveiled in the 50th and final installment.

To say that Jean Beliveau is an all-time great player is, of course, correct. But it doesn't tell the whole story.

From his debut with Montreal Canadiens as an amateur during the 1950-51 season to his finale in Game 7 of the 1971 Stanley Cup Final, when he won his 10th championship as a player, Beliveau excelled in all facets of the game while playing with the smooth grace that's almost never seen in any sport. His greatness was such that the Hockey Hall of Fame waived its mandatory three-year post retirement period and inducted Beliveau in 1972 alongside his longtime friend and rival Gordie Howe (who also retired in 1971).

And like Howe, his playing career was only the first act. He got his name on the Stanley Cup seven more times as an executive with the Canadiens. His selfless charity work, done quietly, benefitted thousands of people, many of whom had never seen him play. The grace and kindness he showed while dealing with people made him, along with Howe, among the great ambassadors in hockey history.

But one of the great careers in NHL history nearly didn't happen.

The Canadiens ended up having to buy an entire league to get Beliveau to turn pro; he was already earning more money than many NHL players while playing for the Quebec Aces in the Quebec Senior Hockey League. He finally signed with the Canadiens in October 1953, was a First-Team All-Star in his second season, then won the Hart and Art Ross trophies in 1955-56 while helping Montreal win the first of an NHL-record five consecutive Stanley Cup championships.

Appropriately, Beliveau retired on top in 1971, helping the Canadiens upset the regular-season champion Boston Bruins in the Quarterfinals, defeat the Minnesota North Stars in the Semifinals and outlast the Chicago Blackhawks in a seven-game Final. He had 22 points, including a League-best 16 assists, in 20 playoff games at age 39.

"It is hard, but I will play no more," he said on June 9, 1971. "I only hope I have made a contribution to a great game."

In his NHL100 profile of Beliveau, NHL.com columnist Dave Stubbs outlined some of what made Beliveau special:

"He lived every day of his adult life in the public eye without once putting a foot out of place; for more than half a century, from 1953 until the first of two strokes cut into his legendary energy, he answered by hand each of the thousands of pieces of fan mail that came his way.

"If the incandescent [Maurice] Richard, who died of cancer in 2000, was often viewed as the furnace of the Canadiens, then surely Beliveau was the conscience, even the soul of the franchise, a steady compass who unfailingly led by his sterling reputation and the example he set.

"On the ice and in the dressing room, Beliveau fully filled the huge skates of the Rocket, something that seemed unthinkable when Richard retired in 1960.

"Beliveau died on Dec. 2, 2014, following a long illness. As was the case with Richard in 2000, Beliveau lay in state at Bell Centre, where thousands of loyal fans and a great many whose lives had been profoundly touched by him, his actions or just his reputation filed in to pay their respects. His funeral was carried bilingually on live television in Canada, flags across the country flying at half-staff."

Artist Tony Harris has his own memories of a meeting with Beliveau.

"I had the great pleasure of meeting Mr. Beliveau a few years before his passing," he said. "I was commissioned to paint his portrait for a charity auction and he had graciously agreed to sign it. The visit was scheduled for only 15 minutes, but he insisted we stay to have coffee and two hours later we left feeling like we'd won the lottery. What a special man."