Foligno humbled by Masterton Trophy nomination after kids' health issues

Blue Jackets forward finalist for award citing perseverance, dedication

Landon had a cast running from his hip down his leg, necessary because the 3-year-old broke his right leg in a trampoline park.

Hudson was lying in a hospital attached to a ventilator, his 22-month-old lung collapsed, the near-tragic result of a bout with pneumonia.

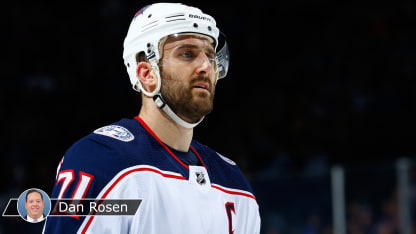

This was November through March for Columbus Blue Jackets captain Nick Foligno and his wife Janelle.

Milana, Landon and Hudson are their kids. They're better now, spending the summer at their house on Long Lake in Sudbury, Ontario, Milana having graduated kindergarten in Columbus earlier this month.

But the perspective gained through the most tumultuous time they've had as a family for Foligno is still as fresh as the wounds his children endured.

"My wife and I now, it's funny, you're a few months removed, and we were just laughing, like 'Holy, the crap we went through,'" Foligno said. "It's not funny, but it's crazy and you laugh now because you just grinned and beared it. You just get through it and then you look back and it's like, 'Oh my God, what the hell happened this year? Do we have to rethink our lives here?' But, no, it was just crazy things that happened all at once."

Foligno will be in Las Vegas this week for the 2019 NHL Awards presented by Bridgestone on Wednesday (8 p.m. ET; NBCSN, SN). He's a finalist with New York Islanders goalie Robin Lehner and San Jose Sharks center Joe Thornton for the Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy, given to the player who best exemplifies perseverance, sportsmanship and dedication to ice hockey.

It's a strange honor for Foligno, he said, because staying dedicated to his profession and his family at the same time is something he has always strives for. That it was harder this season doesn't mean he thinks he deserves an award for it.

"I never want it to come across as 'Poor me'," Foligno said. "I just want to make sure people understand that I'm not complaining. This is my life, and I'm blessed in a lot of ways. There are people who are going through it way worse than I am. That's why this award, it feels weird. It's humbling and I appreciate it, but it's something that feels weird to me because I get to play a game for a living, and I've got a pretty good life considering all this stuff."

\\\

Milana's battle started almost immediately after she was born on Oct. 14, 2013. She was diagnosed with a rare congenital heart disease called mitral valve arcade. Her mitral valve wasn't closing to prevent blood flow back into the heart, a problem that leads to heart failure.

When she was two weeks old, Dr. Sitaram Emani, the director of complex biventricular repair program at Boston Children's Hospital, opened her chest and inserted a replacement mitral valve in her heart that was set to expand as Milana grew.

She was the 17th baby in the world to have this procedure.

The valve was working until November, when Milana was diagnosed with endocarditis.

"It is pretty much an infection of the valve, so we knew she'd need to get [the valve] out," Foligno said. "The problem was you need to get rid of the infection first. They don't want to go in and cut a kid open unless it's an emergency and have this infection running rampant. The other valve could get infected. So, you get on a course of antibiotics for nearly two months. That's what brought us to January."

Milana had an IV line in her arm the entire time. She couldn't go to school because of the risk of further infection. She was on a course of antibiotics just to keep her healthy, so she could travel from Columbus to Boston for her surgery to remove and replace the valve.

Foligno left the Blue Jackets on Dec. 30 to go to Boston with Janelle for Milana's surgery, leaving Landon and Hudson with Janelle's parents, Michelle and Marc Forest, who flew down from Sudbury.

"I know when my kid gets a cold it feels like the end of the world," Blue Jackets forward Cam Atkinson said. "I don't know how he does it."

The rest of the team kept up to date with what was happening with Milana through a group text. It would typically be one or two players communicating with Foligno and relaying the news and updates to the rest of the team.

"It would probably be overwhelming for him if we were all texting him," Blue Jackets defenseman Zach Werenski said. "That was the easiest way to do it for him. It was really scary. When you do think about it, what we go through isn't pressure; what he went through as a family, that's pressure."

The surgery was a success.

Milana got a new valve that is big enough for her to grow into. The risk for infection still exists, but if all goes well the new valve should last her between 8-12 years before she would need another operation, but Foligno said the doctors might not have to open her heart again.

"There is a chance that they could actually put a valve inside this valve and go through a catheter in her leg to do it, so they wouldn't require open-heart surgery," Foligno said. "That's the hope if she can get that far [with the new valve]. She has to be a certain size in order to go through her vein in her leg, but technology advances so much and who knows what will happen in eight to 10 years anyway. There could be something better on the market."

Milana's recovery was quick too, shocking the doctors. They were home 10 days after arriving in Boston. Foligno missed four games. He was in the lineup Jan. 10 against the Nashville Predators.

Just over two months later, he had to take another leave of absence, this time to be with Hudson in the hospital.

\\\

Before Hudson's ordeal, Nick and Janelle figured they'd try to do something nice for Landon so they took him to a trampoline park.

"Terrible idea," Foligno said, "but it sounded like a great idea at the time."

Landon fell awkwardly and broke his right leg.

"We're trying to get some 1-on-1 time with him and unfortunately it turns into that, so now he's got to deal with trying to function with a broken leg and a cast on from his hip down. He missed out on school because he couldn't quite go."

With Milana recovering and Landon laid up, the last thing they needed was something to happen to Hudson.

Seven days after Landon broke his leg, Hudson came down with pneumonia. It started as a mild case, Foligno said. They went to the hospital and he was treated with antibiotics for two days during the NHL All-Star break.

"He got better and we moved on," Foligno said. "Then about three weeks later he got the same kind of thing. It was going around. Respiratory viruses were insane, especially in Columbus. So he got another one where he got the croup-style cough going and we're like, 'Oh boy, hopefully this doesn't turn into anything.'

"Sure enough, the day I head to New York my wife calls me that night and says she's at the emergency room with Hudson because he was breathing again like he was before."

Janelle said it wasn't bad and since they had so much experience with hospitals they decided it would be OK for Foligno to play the game at the New York Islanders on March 11.

He returned home to play against the Boston Bruins the next night. The forward also played against the Carolina Hurricanes on March 15, the last game before a four-game, 10-day road trip.

"He just wasn't getting better," Foligno said.

Foligno spoke with coach John Tortorella and told him what was going on.

"[Tortorella] is amazing with this stuff," Foligno said. "He just says, 'Whatever you need. Figure out your family and worry about hockey after.' That's what happened."

Hudson kept deteriorating. His lung started to collapse. He had to be put on a ventilator.

Foligno skipped games road games against the Bruins, Calgary Flames, Edmonton Oilers and Vancouver Canucks.

Tortorella talked to Foligno two or three times a day through the ordeal.

"We never talked hockey," Tortorella said. "Never. He wanted to. We weren't going to because there were more important things going on than hockey."

Foligno said, "The team was in the toilet at that time too, for lack of a better word."

He was torn up inside, worrying about Hudson but also his team, which had gone all in at the 2019 NHL Trade Deadline, acquiring forwards Matt Duchene and Ryan Dzingel and keeping forward Artemi Panarin and goalie Sergei Bobrovsky, four potential unrestricted free agents in all.

Columbus lost the first three games of the road trip Foligno missed. It wasn't in a playoff position.

The Blue Jackets had heart-to-heart team meetings before they played at Vancouver on March 24. Foligno wasn't there, but he stayed involved by texting with defenseman Seth Jones, Atkinson and forwards Boone Jenner and Brandon Dubinsky.

"They were respecting my situation, but I wanted to know what's going on because the last thing you want to do is come back to a team where you're like, 'What the heck happened?'" Foligno said. "I also told them that it was nice to see them take ownership of things. I think it gave them some confidence. This is as much their team as it is mine."

The mojo started to turn.

"I don't know, but all of a sudden Hudson started to get better and our team started to heal itself too," Foligno said. "Literally the day they won in Vancouver was the day he got his breathing tube out. It's kind of a weird side of it."

Foligno was back on the ice with the Blue Jackets when they returned home to play the New York Islanders on March 26, starting a 7-1-0 run to end the season, a stretch that helped them clinch the second wild card into the Stanley Cup Playoffs from the Eastern Conference.

The entire family got to experience the first-round sweep of the Tampa Bay Lightning, the first playoff series win in Blue Jackets history. They were together for the ups and downs of the second-round series against the Bruins, which ended in six games, Columbus on the losing side.

"It makes you realize how vulnerable you are in those moments," Foligno said. "You think you have it all figured out and when health comes into it nothing else matters."

Foligno now thinks of the strength of his kids, especially Milana and how she accepts her heart disease, deals with it and still goes on being a kid. His thinks about the strength he gains from them.

"You try to be strong for them, but it actually works the other way where their strength is actually what makes you strong," he said. "I just couldn't be more proud of them and their fight. It humbles you as a parent."