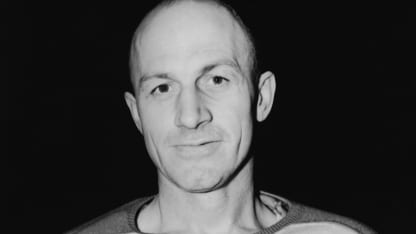

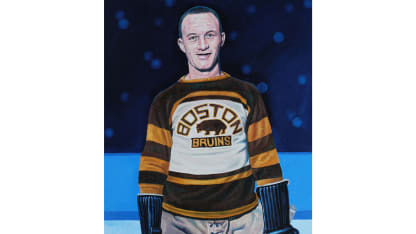

For all of his bellicosity, the 5-foot-11, 190-pound Shore was nobody's goon. He was the rare defenseman who would use his speed and stick-handling skill to carry the puck into the opponent's end, doing it with a stand-up skating style and almost a defiance, daring people to try to derail him as he barreled up the middle of the ice. Shore had 12 goals as a rookie and 62 goals over his first five seasons, going on to capture four Hart Trophies as the NHL's MVP and helping the Bruins win the Stanley Cup twice.

"He was the only player I ever saw who had the whole arena standing every time he rushed down the ice," longtime Bruins trainer Hammy Moore said. "He would either end up bashing somebody, get into a fight or score a goal."

It was this almost unheard-of hybrid -- frontier feistiness braided with an artisan's touch -- that constantly placed Shore in the middle of mayhem, on the ice and off.

Maybe the most legendary Shore story began on a winter's night in Boston, Shore riding to the station with a friend to catch the Bruins' overnight train to Montreal. The friend's car broke down, and rather than abandon him and catch a cab, Shore got under the hood to fix it. They finally got to the station, but the Bruins train had left, so Shore convinced a cabdriver to drive him more to Montreal, some 320 miles away, for $100.

So began a harrowing trip northward, traversed in blizzard conditions on serpentine, snow-covered roads in the White Mountains, with a driver and vehicle wholly ill-equipped for the journey. Shore wound up doing the driving himself, flagging down a truck driver to get a set of chains, and shoveling the car out of multiple ditches, before he hitched a ride on a horse-drawn sleigh to a train station.

The 22-hour trip got Shore to Montreal just in time for the game. Coach Art Ross fined him $200 for being late, and then marveled as Shore, his face chapped red with vestiges of frostbite, played one of the best games Ross had ever seen.