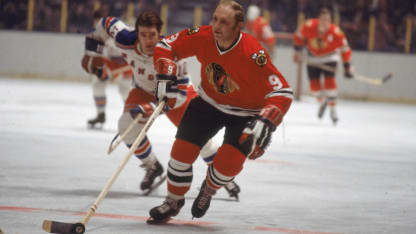

If there ever were an athlete who embraced that mentality, it was The Golden Jet, an electric left wing who evoked and enjoyed the roar of the crowd during 15 seasons with the Chicago Black Hawks, as they were then known. When Hull gathered the puck and went on a rink-length rush at Chicago Stadium, or any building in the NHL, fans rose from their seats and held their breath, as did opposing goaltenders.

"The best part about coming to Chicago was that Bobby Hull was on my side," said Hall of Fame goalie Glenn Hall, who was traded to Chicago from the Detroit Red Wings in 1957. "But I still had to face him and his shot in practice.

"The idea was not to stop that thing, but to avoid getting killed. Every once in a while, Bobby would fire the puck and it would fly into the stands at the Stadium. If the cleaning ladies were up there, you should have seen them scatter. They looked like Olympic sprinters."

BOBBY HULL CAREER TOTALS | View Full Stats

Games: 1,063 | Goals: 610 | Assists: 560 | Points: 1,170

Without any minor league duty, Hull graduated from St. Catharines of the Ontario Hockey League to the Black Hawks in 1957. After scoring 13 goals as a rookie, Hull developed into a prolific and charismatic presence. When his statue was unveiled outside the United Center (along with one of Stan Mikita) in 2011, Hull stood as the franchise career leader in goals with 604, not including 62 in the playoffs, four of which came in the 1961 postseason and helped the Black Hawks win the Stanley Cup. He joined the Winnipeg Jets of the World Hockey Association in 1972, scoring 303 goals in seven seasons. After the Jets joined the NHL in 1979-80, he had four goals for them in 18 games, then two more later that season with the Hartford

Whalers, playing with Gordie Howe in the final stop for each.

Hull's arsenal featured not only a blistering slap shot once clocked at 119 mph, but bull rushes to the net, where he presented all sorts of problems for goalies and the succession of "shadows" who tried to neutralize him. Opponents invariably designated at least one checker, sometimes two, to try to diffuse this offensive machine. But Hull, who as a child gravitated to the outdoors near the family home in Pointe Anne, Ontario, was a physical marvel, so massively muscled that he often was described as the "perfect mesomorph." When he didn't spend hours on the rink as a youngster, Hull pitched hay and chopped down trees. Hull put that imposing physique (he had 16-inch biceps) and resolute skating style to good use in open ice and tight quarters.

Hull's first NHL goal came in his seventh game. He recalled tumbling to the ice and sliding into the cage with the puck beneath him beside Boston Bruins goaltender Harry Lumley. Not exactly a harbinger of serial highlights to come.