Imagine a situation where teammates would be punished for being the architects of a Stanley Cup-winning goal.

Hard to believe, isn't it?

But this unlikely event took place during and after Game 5 of the 1951 Stanley Cup Final between the Toronto Maple Leafs and Montreal Canadiens on April 21, 1951, at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto.

Two wrongs make right for Maple Leafs in 1951

Gardner's commitment to defense, Barilko's gamble leads to Stanley Cup win against Canadiens

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

The Maple Leafs led the best-of-7 series 3-1, with all four games decided in overtime. Maple Leafs general manager Conn Smythe and coach Joe Primeau, however, were worried about one opposing player.

Maurice "The Rocket" Richard was in his scoring prime and would lead the 1951 Stanley Cup Playoffs with nine goals and tie for the lead with 13 points. He had scored in overtime in Game 2 at Toronto.

The Maple Leafs had alternated between two goalies, Turk Broda and Al Rollins. Years later, Rollins revealed that Richard had a mesmerizing effect on goalies because of his "searchlight" eyes and fierce determination to score.

"Smythe and Primeau were concerned that Richard still could break open the series for Montreal if he ever got another overtime goal," Rollins said. "[Richard] was one of a kind, and they gave us special orders on how to stop him in the fifth game."

The plan was to assign left wing Harry Watson to shadow Richard all over the ice.

But that wasn't enough since Richard's speed could propel him on an attack faster than any player could contain him, so Primeau contrived a backup plan.

When Richard was on the ice, no Maple Leafs defenseman could skate into the offensive zone. Primeau said breaking that rule was punishable by a $500 fine.

"The idea," Rollins said, "was to prevent a [Richard] breakaway, especially if we went into overtime."

Richard opened the scoring for the Canadiens in Game 5, but for most of the rest of the game the Primeau plan seemed irrelevant. The Canadiens led 2-1 until the final minutes of the third period and seemed to have the win in hand.

Desperate to get the tying goal, Primeau pulled Rollins and inserted forward Max Bentley as an extra skater in the final minute of the third period.

With Bentley orchestrating the rush, the Maple Leafs moved the puck deep into the Canadiens' zone. After several frantic flurries, Maple Leafs center Tod Sloan beat Canadiens goalie Gerry McNeil with 32 seconds remaining, tying the game 2-2.

"The balance of power paid off for Toronto," said Globe and Mail sports editor Jim Vipond. "Leafs had strength in depth while Canadiens had heart and desire but couldn't match the manpower."

Still, with a break here or there and the great Richard firing, the Canadiens still could win the game in overtime.

The Maple Leafs took command at the start of overtime. "The Canadiens were inconsequential and indecisive," Montreal Star writer Baz O'Meara said. "The tired defense was wobbling in front of McNeil."

Watson led the decisive rush up the right side of the ice, carrying the puck behind the Canadiens net.

His linemate, right wing Howie Meeker, reached the puck at almost the same time as Canadiens defenseman Tom Johnson. Meeker won the battle and took control behind the net.

His plan was to swerve sharply in front of the goal and take McNeil by surprise. The play almost worked, but McNeil covered up in time. He stopped the shot by Meeker and the rebound by Watson.

But McNeil had trouble controlling the second rebound and fell to the ice while the puck slid out to the blue line.

Maple Leafs center Cal Gardner was in perfect position to get the puck and put it past McNeil, who was having difficulty regaining his stand-up position. But instead he made no attempt to get it.

Sitting in the stands, Smythe was horrified. He turned to a fellow member of the Maple Leafs staff and said Gardner would be fined $1,000 for passing up what could have been the winning play.

Then another Maple Leafs fine was in the offing, this one for $500.

Defenseman Bill Barilko knew about the fine and remembered Primeau's warning about not drifting too deep into the offensive zone. Barilko deliberately had placed himself "safely" on the wrong side of the blue line.

But when Barilko saw Gardner ignore the puck as it came toward him, he had to decide whether to chance getting caught out of position and rush for the puck or to play safe and allow it to drift over the blue line, where he could organize another rush. Barilko decided to gamble.

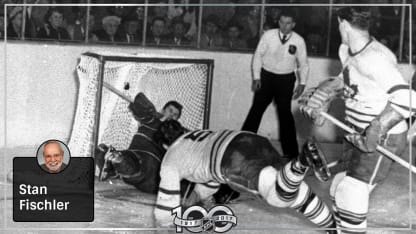

Literally running on the tips of his skates, the defenseman lurched over the blue line and, in one motion, hurled his 5-foot-11, 185-pound body at the puck.

As he shot, Barilko momentarily floated in the air, his legs spread behind him, his hands clutching his stick, which was held horizontal across his body, his head tilted slightly upward so that he could follow the trail of the puck.

Richard was to Barilko's left and Canadiens defenseman Butch Bouchard was to his right, but neither was close enough to block the shot. Gardner was directly behind Barilko.

In that brief second of flight, Barilko's eyes changed from an expression of anxiety to expectant glee. He still was aloft when the puck cleared McNeil's raised right glove and barely eluded the shaft of his stick.

Two minutes and 53 seconds after the start of overtime, the puck hit the back of the net.

By the time Barilko landed, he practically was atop McNeil's right skate. For one breathless split second, the 14,577 witnesses to one of the greatest hockey games ever played held their breath.

Then they realized it was over.

"The walls of the rink vibrated with noise," Montreal Gazette columnist Dink Carroll said. "Toronto players left the bench and swarmed on the ice to join their teammates as they mobbed Barilko.

"The defeated Canadiens stood still, looking disconsolate, until they remembered their manners and skated over to congratulate the winners."

Primeau was one of the first on the ice. He dashed to Barilko, hugged him several times, and shouted, "I won't fine you for charging on that one!"

Gardner wasn't so lucky. Smythe was delighted with the victory but unforgiving over Gardner's seemingly illogical refusal to capitalize on the earlier scoring chance.

The next day Gardner was ordered to Smythe's office and was told the $1,000 fine would stick, Stanley Cup win or not.

"I really caught it from Smythe," Gardner said. "Conn told me, 'You should've got that goal.'"

Convinced that he was in the right and not fearful of Smythe's wrath, Gardner shot back that there was proof that he didn't deserve punishment. Gardner knew that the Maple Leafs were the only NHL team to film of every game and use them as a tool the way NHL teams use video presently.

What he hoped to show Smythe was that his edict that Richard should be covered at all times had to be fulfilled. It was Watson's job but he was on the other side of the ice when the puck came out.

Gardner said, "I told Smythe that if he were to check the film of the goal, he would see that [Richard] was uncovered and that I had to be watching him and not the puck. When we watched the film, Smythe was now convinced that I did the right thing by watching Richard and letting Barilko do his thing.

"Later on, the papers ran photos of the play with the puck in the net. You'll see me right behind Barilko, and over to the right of me you'll see [Richard]. He was the guy it was my job to watch. And I did."

Smythe rescinded the fine.

Through spring and early summer Barilko was Canada's new hockey hero.

On Aug. 26, Barilko was invited to take an airplane ride over Northern Ontario lake and forest country with Dr. Henry Hudson, a pilot friend. A native of Timmins, Ontario, Barilko was familiar with the area and its bountiful fish and game, and he looked forward to the flight with his usual enthusiasm.

© Claus Andersen/Getty Images

He bade his pals goodbye and said he would report to training camp in top shape.

It was the last time anyone heard from Barilko.

It wasn't until June 7, 1962, more than a decade later, that the wreckage of Hudson's plane was found, six weeks after the Maple Leafs won their next Stanley Cup championship. The remains of Hudson and Barilko were found strapped into their seats.

The Maple Leafs memorialized Barilko by retiring his No. 5, which hadn't been worn since his Cup-winning goal.