AIR FORCE ACADEMY, Colo. -- Mark Manney didn't go to the U.S. Air Force Academy to become a pilot. His family had no military background. He had never even been on a plane before traveling to the academy for his freshman year in 1979.

NHL Stadium Series puts impact of Air Force hockey in spotlight

Program at academy, site of Avalanche-Kings game, 'prepares you for serving'

"To be honest," he said, "I really just wanted to play Division I hockey."

Well, not only did he end up flying in the Air Force, he ended up flying Air Force One.

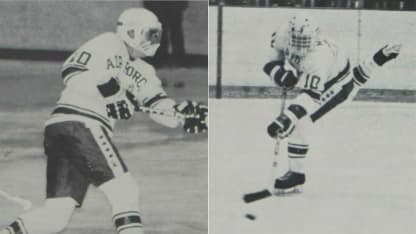

Manney was a good hockey player. The forward from Moorhead, Minnesota, led the Falcons in scoring in 1981-82 with 53 points (27 goals, 26 assists). He had 15 power-play goals, still tied for the team record for most in a season.

But he found another calling at the academy. After graduating in 1983, he went to pilot training and spent almost 23 years in the Air Force, flying Air Force One from 1999-2004 -- the last two years of President Bill Clinton's tenure and the first four of President George W. Bush's. He flew Bush to New York after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and Baghdad to visit troops on Thanksgiving in 2003.

"I got into the school and then decided I wanted to be a pilot," he said. "It seemed like a pretty neat job. For a kid who didn't get to travel much, you certainly would get to see the world being a pilot."

Manney is an example of what the hockey world should see when the Colorado Avalanche and Los Angeles Kings play at the academy in the 2020 Navy Federal Credit Union Stadium Series at Falcon Stadium on Saturday (8 p.m. ET; NBC, SN360, TVAS2).

Air Force has a hockey history that goes back to the beginning of the academy. It has a Division I program and men's and women's club teams. The Division I program has made the NCAA Tournament seven times and the Elite Eight three times in the past 13 seasons. It has produced four All-Americans and three finalists in the voting for the Hobey Baker Award, given annually to college hockey's best player. It has produced minor pro players.

Most important, it has helped produce military leaders.

"You learn more about leadership being on an athletic team, especially one at a high level, than you do in any classroom or seminar or what have you," said Manney, who retired as a lieutenant colonel in 2004 and coaches hockey at Andover High School in Andover, Minnesota. "Working within the group and understanding your role and knowing that others depend on you to do your job prepares you for serving in the military so much. A lot of the techniques and things I used in leading people later in my career came from the locker room rather than from the classroom."

Manney remembers a goalie named T.J. O'Shaughnessy. That goalie graduated in 1986 and went on to become an F-16 pilot who flew more than 3,000 hours, including 168 in combat. He is a four-star general leading the United States Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command.

Air Force hockey alumni include Mike Polidor, a F-15E pilot who won the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism and the Jabara Award for airmanship for leading a mission that saved lives in Afghanistan in 2009, and Mitch Torrel, a special tactics officer who led a unit that helped rescue a boys soccer team from a cave in Thailand in 2018.

Watch: Youtube Video

The Stadium Series will shine a spotlight on the place that shaped them and so many others.

"The most important thing is to learn a little bit about the kids who go to school there and how they're such great representatives of our country and their communities individually," Manney said. "You can play a sport and excel at it but also serve your country and your community in a greater capacity than being an athlete.

"Some of these kids are going to go on to be Rhodes Scholars and congressmen and senators and generals, and will help protect us and serve us for years into the future. People who watch the game should know that the country is in great hands with the young men and women at the Air Force Academy."

* * * * *

This outdoor game recalls the roots of hockey at the academy. When the academy moved to this location in 1958, cadets started playing intramural hockey outdoors, wearing football and lacrosse equipment in the courtyard of Vandenberg Hall.

Then came the Father of Air Force Hockey, Vic Heyliger, who played 33 games as a center for the Chicago Black Hawks (then two words) -- seven in 1937-38 and 26 in 1943-44 -- and coached the University of Michigan to six NCAA titles in 13 seasons from 1944-57.

Heyliger arrived at the academy in 1966 to coach the club team. He became Air Force's first varsity coach when the program began Division I play in 1968-69 and went 85-77-3 in six seasons, including 25-6-0 in 1971-72.

Air Force hockey's success is remarkable for two main reasons:

One, the program can recruit only U.S. citizens. No Canadians. No Europeans.

"It takes a certain population from the sport of hockey off the table from the very beginning," Air Force director of athletics Nathan Pine said.

Two, the program must find recruits who are not only good enough to play Division I hockey but can handle all the other demands of being a cadet and will commit to serving in the Air Force for at least five years.

"We produce graduates for the nation," said Brig. Gen. Linell Letendre, the dean of the faculty. "We produce graduates who are going to lead our Armed Forces, our Air Force and our Space Force. And so what do we want that product to be? We want that product to be a person of integrity, a person of character, a person who has been through and exposed to a wide variety of experiences."

The academics are rigorous. The academy offers 32 majors but requires 29 core classes and more credit hours than a civilian school. A physics major takes courses in English, history and political science. An English major takes courses in aeronautical, astronautical, mechanical and electrical engineering. Each cadet graduates with a Bachelor of Science degree.

"We don't have less time on the ice here for our hockey players, but they are balancing that normal intercollegiate practice time, lifting time, with taking five to six classes, sometimes seven, a semester," Letendre said.

Many not only survive, they excel. Air Force has produced seven Academic All-Americans, including Kyle Haak, the captain of the 2018-19 team, who majored in physics and graduated with a 3.91 grade-point average. He is now working on his doctorate in public policy at the Rand Corp.

"The average GPA for our hockey players is above a 3.0, which means that my hockey team is on my list," the dean said with a smile.

On top of that is military discipline and training. Cadets report to morning officer development in uniform at 0630 hours; gather for noon meal formation and march to Mitchell Hall for lunch; go through everything from drills to inspections; and abide by an honor code. Each cadet becomes an officer, commissioned as a second lieutenant.

"Really, the cadets run the cadet wing, from their cadet wing commander all the way down to the individual cadet who may not have a job in the squadron," said Col. Clarence Lukes, the vice commandant of cadets. "Their day is run by cadets. It's their life, but it's also an opportunity for them to develop into leaders."

Frank Serratore, the hockey coach at Air Force since 1997, acknowledged that he has a smaller pool of talent from which to draw. But other schools have their own challenges too, and he has a lot to offer.

"We have a very competitive Division I program," Serratore said. "We've got great facilities. We treat our kids like pros. With that, they get an Ivy League-type education here. With that, the financial aid package is second to none. Not only are they on a full ride, they're on more than a full ride. They get paid to go here.

"And when they're done, this isn't just about the next four years for them. It's about the next 40 years for them. When they're done here, they're set up with a career."

The careers go beyond the Air Force too. Alumni are in high demand if they leave the service, because employers know what they have endured and accomplished.

"The challenge for us is finding the right puzzle pieces, finding the right kid and the right family that possess those attributes," Serratore said. "They are out there, and when we find them, it's not a hard sell."

* * * * *

These are unique individuals.

Take Matt Pulver from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin. His brother, Mitch, played club hockey at the U.S. Naval Academy. His sister, Allison, ran varsity track at Navy.

"Just seeing what they went through and what it means to go to an academy and put on the uniform every day, from a very young age I knew I wanted to follow in their footsteps," Pulver said. "As I got older, I knew I was going to be able to play Division I hockey."

Navy didn't have a Division I team, but Air Force did. Pulver had no interest in other schools and committed at age 16.

He is now a senior forward and Falcons captain. He showed around Avalanche captain Gabriel Landeskog when Landeskog pretended to be a cadet for a day Jan. 13.

"I think just having the opportunity to serve was my end goal," he said. "I had no real passion to play pro [hockey]. I just kind of wanted to be an officer, and I'll be able to fulfill my goal hopefully in four months."

Take the members of the women's club team, in its second official season. Some are experienced hockey players; the rest are learning. Each cadet has to participate in sports at the Division I, club or intramural level.

"You'd think it'd be super frustrating," said Sarah Warner of Maplewood, Minnesota, a senior forward and the team captain. "Half the team played in high school. They know how to play. They're really good skaters. And half the team, you actually have to help them put on their gear the first day. But then you look at how hard everyone's working. You see the commitment and dedication. It makes it worth it."

Kellyann Indyk of Boca Raton, Florida, and Susan Yeung of Long Island, New York, are among the newcomers. Sometimes they have risen at 3:30 a.m. to do extra work on the ice at 4 before going through the rest of their demanding day.

"We would look at the calendar and see when open slots were available, and whenever we had the chance, we would go," Yeung said. "We saw how good the other players were, so we just tried to practice as much as we could."

Yes, it's difficult. The Division I team has study halls on the Thursday and Saturday of each road trip. The players are away from the academy but not on leave. They cannot afford to fall behind in their classes.

"Like, you think hockey road trips, you get to rest a little bit," Pulver said. "But I mean, the grind never really stops here, because we do take so many credits and we do take hard classes. So you can't take your foot off the gas, otherwise you're going to get sunk pretty quick."

But the ice is a refuge.

"Going on the ice is a way to just blow off steam," Indyk said.

Beth Gordon of Boston saw her friends having so much fun playing hockey that she decided to join the team herself.

"We're always looking for new recruits," she said.

Do you have what it takes? Would you have had what it took at that age?

In the end, no matter what happens when the Avalanche and Kings play at Falcon Stadium, fans who attend or tune in on television should take away one thing most of all.

"They should be proud of their United States Air Force Academy," said Lt. Gen. Jay Silveria, a 1985 graduate who became a fighter pilot and is now superintendent. "It's an amazing place. The young men and women that are stepping up to serve their nation, making that decision when they're 18, 19 years old to show up here and serve their nation, we should all be proud of them and the institution."