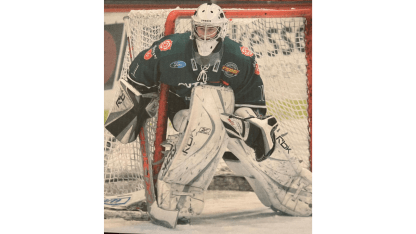

His unlikely career as the most successful German-born goalie in NHL history still is all about the journey for Philipp Grubauer, even when not contemplating his arduous path to get there.

Whether winning a Stanley Cup, vying for a Vezina Trophy, stealing the Kraken franchise’s debut playoff series, owning a local brewery or grooming his pet horse, the 34-year-old doesn’t waste a day. Grubauer has done that and more whether connecting with fans or building community ties and a full-time Pacific Northwest home, all while still making it back to Germany four weeks every summer.

But ask Grubauer about defying improbable odds as a goalie from small town Upper Bavaria, whose exposure to NHL highlights growing up was watching former Canadian TV pundit Don Cherry’s Rock‘em Sock’em Hockey video cassettes, he’ll shake his head and say his pro athlete schedule doesn’t afford time to “sit down and soak it all in.” That is, until his heritage became a discussion point after being named Germany’s goalie for next month’s 2026 Olympic Winter Games Milano Cortina.

“I’ve thought about it a little bit,” Grubauer admitted. “But I probably won’t digest it all or run it through my mind until I retire.”

But he conceded things might change once landing in Milan. Wearing his nation’s colors will be an experience unlike any other and Grubauer admits it could prompt reflection on “the sacrifice that it took to get there.”

Those tribulations, whether he’s thinking about them or not, are in greater focus as Grubauer posts numbers unseen since his 2021 Vezina finalist Colorado Avalanche days. Grubauer, playing in a tandem with Joey Daccord, is 11-5-3 with a 2.34 goals against average and .919 save percentage after a difficult prior season that included relegation to AHL Coachella Valley.

He’s lost only two of his last 11 starts while allowing 22 goals, pulling the Kraken into playoff contention and conjuring memories of his 2023 playoff win over his former Colorado squad. He’ll look to build off that at the Winter Olympics, using the tournament as a potential springboard to another Kraken playoff run.

In some ways, Grubauer never stopped representing Germany from the time he left at 16 for the Canadian major junior ranks. An anomaly from a European country known mostly for soccer, there wasn’t much Grubauer did that wasn’t a first.

Milan should feel like a homecoming beyond wearing his national team jersey. The Olympic venue is only a 320-mile drive south, crossing two borders on highways skirting the Austrian Alps, from Grubauer’s rural hometown of Rosenheim. Though its dairy farms and horse ranches allowed young Grubauer to earn money cleaning barns and milking cows, the town of 65,000 is about hockey passion.

“We breathe hockey in my hometown,” Grubauer said. “You go into the bigger cities, it’s all about soccer. But in my hometown, hockey was it.”

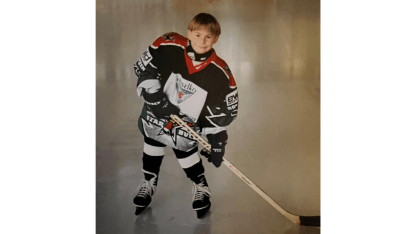

The Rosenheim Starbulls have existed in various incarnations for 98 years at differing levels of the domestic pro Deutsche Eishockey Liga circuit. Grubauer at age 3 began Starbulls youth hockey as a defenseman, becoming a goalie three years later and playing both positions until he was 14.