If O'Ree weren't focused on his trailblazing, he was reminded of it before the game by his coach, Milt Schmidt, who told the 22-year-old the Bruins, as a whole, understood the enormity of his debut.

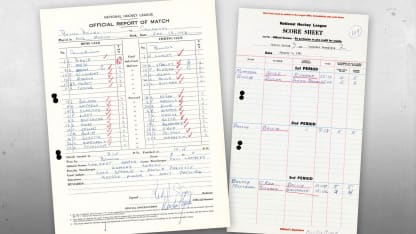

But O'Ree's historic appearance garnered only passing mention in the following morning's Montreal Gazette, which noted in the third paragraph of its report: "The game also marked the debut of Willie O'Ree, first Negro to play in the NHL, at left wing for the Bruins. … A fleet skater, he had one good scoring chance on a play with [Jerry] Toppazzini in the third period. He lost it when he was hooked from behind by Tom Johnson.

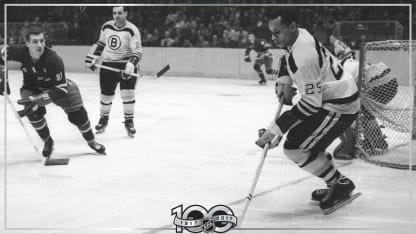

Skating on a line with right wing Toppazzini and center Don McKenney, O'Ree wasn't deemed worthy of a newspaper photo; the four published images all were of Bruins goalie Harry Lumley, who shut out the Canadiens with a 28-save effort.

O'Ree acquitted himself well that night at the Forum. He didn't have a point but he wasn't out of place.

"There was nothing said about Willie O'Ree breaking the color barrier or being the first of his race to play in the NHL," he told Mortillaro for her book. "It didn't really dawn on me until the next day. I was just happy to play with the Bruins and be on the winning team."

In 2007 interview with NHL.com, O'Ree said, "I was expecting a little more publicity. The press handled it like it was just another piece of everyday news. I didn't care much about publicity for myself, but it could have been important for other blacks with ambitions in hockey. It would have shown that a black could make it."

Indeed, it wouldn't be until 1974 that the second black player, Mike Marson, would skate in the NHL, for the Washington Capitals.