"Dad always sat in his front-row spot in the corner on the penalty-box side and he'd go back and forth for each period. It was fun to be able to experience that," he said.

Brodeur laughed when it was suggested to him that he might have hot-dogged a save or two, with a little extra mustard, for his father's benefit.

"Nah, when you play hockey you have to be focused," Brodeur said. "Before a face-off I'd wink at him -- we have some great pictures of that stuff -- but if I did showboat, it was on my own, not because my dad was there."

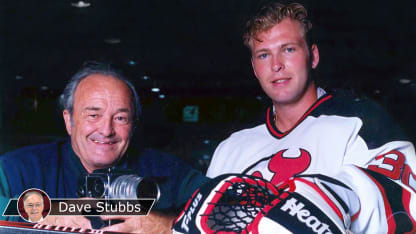

Denis, who published four books of his photography, including one devoted exclusively to Martin, was at Bell Centre on March 14, 2009, when his son tied Canadiens icon Patrick Roy's NHL record of 551 wins. And he was at Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey, three nights later, when his son broke the record. Both were commemorated with souvenir father-and-son photos.

And in December 2009, as Martin neared Terry Sawchuk's NHL record of 103 shutouts, his father walked into a Montreal antique shop and happened upon a photo that took his breath away. He bought that image, of Sawchuk, and framed it beside one of Martin for the record-breaking occasion, with plaques beneath them indicating 103 and 104.