TORONTO -- The late

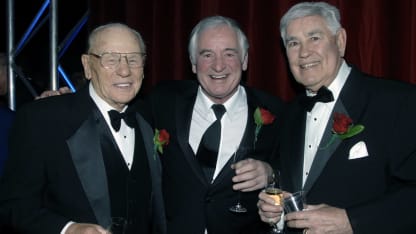

Jean Beliveau

faced dozens of NHL goaltenders during his Hall of Fame career. But in some ways, there was none who posed a greater challenge than

Johnny Bower

of the Toronto Maple Leafs, a man who would become a dear friend.

On Wednesday afternoon, thousands will gather at Air Canada Centre -- family, friends, fans, former teammates and opponents, members of the Maple Leafs current team and organization, and NHL and civic dignitaries -- to celebrate the life and career of Bower, who died on Dec. 26 at age 93.

Bower was champion on ice, beloved gentleman off it

Friends, family, former foes to celebrate life, career of Hall of Fame goaltender, who died Dec. 26