Bettman hiring as NHL Commissioner 30 years ago changed face of hockey

How Board of Governors meeting on Dec. 11, 1992, set League on new course for success

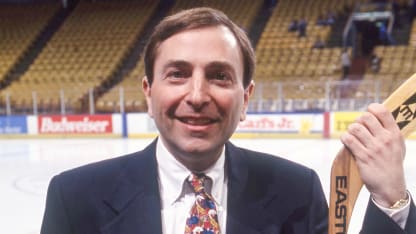

Gary Bettman pulled it on 30 years ago, after he was elected the NHL's first commissioner at the Board of Governors meeting at The Breakers in Palm Beach, Florida, on Dec. 11, 1992.

To his left stood Gil Stein, the outgoing NHL president. To his right was Bruce McNall, the owner of the Los Angeles Kings and the chairman of the Board of Governors.

Bettman smiled wide.

He was already an accomplished executive as the senior vice president and general counsel of the NBA. But there were only four leaders of major sports leagues in North America, and now, at just 40 years old, he'd be one of them.

"It was almost like an out-of-body experience," Bettman says now. "It wasn't that I was intimidated or overwhelmed. It was more like … the odds of being selected for a position like that were probably less than the odds of getting struck by lightning."

McNall felt the NHL had caught lightning in a bottle.

He says when he looks back today, he thinks of how the NHL's hiring of Bettman "helped change the face of hockey." He compares it to the Kings' trade for Wayne Gretzky on Aug. 9, 1988.

"In some ways it's equally important to the Gretzky deal -- maybe even more so in some ways, but certainly equal -- because Gary has done a phenomenal job there," McNall says. "That move was really, really important, and history has proven that."

The Board of Governors will return to The Breakers on Monday and Tuesday on almost exactly the 30th anniversary of Bettman's hiring. The meeting will take place in a ballroom named for Ponce de Leon, the explorer who supposedly sought the fountain of youth.

Bettman is 70 and still going strong, running a 32-team NHL with annual revenues approaching $6 billion. The League has grown and evolved in countless ways -- indoors and outdoors, at home and overseas, on TV and online.

His legacy is well documented.

On the 30th anniversary of his start date of Feb. 1, he will match the tenure of his mentor, former NBA commissioner David Stern. He's also on the verge of passing Clarence Campbell, the NHL president from 1946-77, as the longest-serving top executive in pro sports history.

NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman, Bruins owner Jeremy Jacobs and NBA Commissioner David Stern stand outside the construction site of what would become the new arena for the Bruins and Boston Celtics in 1994.

NHL.com reconstructed the story of Bettman's hiring by combing through meeting minutes, poring over news clippings and interviewing people who were there. It provides a snapshot of a time when the League turned toward the future, with behind-the-scenes intrigue and funny moments.

"He's a unique character," says Boston Bruins owner Jeremy Jacobs, now chairman of the Board of Governors. "We really got ourselves a gem of a leader."

In the Winnipeg Sun on Dec. 12, 1992, columnist Ed Willes wrote: "When sports historians look at the development of the NHL, they'll look at the Board of Governors meetings in December 1992 as a watershed mark for the League. … They'll conclude this was the point at which the NHL started to grow up."

Well, here we are.

"I have to say after 30 years that our pick was really good," former Montreal Canadiens president Ronald Corey says. "It was a first overall pick. Oh, yeah. What he did for the League, it's unbelievable. Really unbelievable."

* * * * \

The NHL was not like it is today.

"The League was at a turning point," Corey says.

Hockey had gone Hollywood with Gretzky's arrival in Los Angeles, and the NHL was expanding. The San Jose Sharks joined the League in 1991-92, followed by the Ottawa Senators and the Tampa Bay Lightning in 1992-93.

Still, many owners felt the NHL was lagging too far behind the other major sports leagues. It needed more TV exposure. Annual revenues were about $400 million.

The NHL had its first work stoppage when the NHL Players' Association went on strike April 1, 1992, threatening the Stanley Cup Playoffs. Though the strike ended in 10 days, the new labor agreement was to expire Sept. 15, 1993, setting up another round of collective bargaining. There was no salary cap. The owners felt the players' salaries were eating up too much of the revenue.

It was time for a change.

"As great as Michael Jordan has been, Mario Lemieux dominated our sport this spring playoff," Hartford Whalers owner Richard Gordon told The Associated Press. "And for a time, Wayne Gretzky dominated hockey more than anybody in the history of sport. We never took advantage of it.

"Every owner is a businessman, and he wants to see his assets grow, and we are seeing some erosion in some places. We need a television approach. We need a better international approach. We have great Europeans in our game, and the NBA has beaten us in Europe."

NHL president John Ziegler resigned June 12, 1992. The AP reported that one governor said there was no leading candidate for his replacement, but several names had been mentioned. One of the names the AP listed was Bettman.

The Board of Governors elected Stein interim president and McNall chairman June 22, 1992. The Board created a chairman's executive committee, led by McNall and consisting of one governor from each division: Corey (Adams), Detroit Red Wings owner Mike Ilitch (Norris), Edmonton Oilers owner Peter Pocklington (Smythe) and Philadelphia Flyers owner Ed Snider (Patrick). The committee was tasked with finding a commissioner, not another president.

The NHL had a president as its top executive since its founding on Nov. 26, 1917, but now each of the other major sports leagues had a commissioner, a role with greater powers.

Stein was a candidate. The Board of Governors hired a search firm, Spencer Stuart, that generated many other candidates.

"They came up with some incredible people that ran big companies," McNall remembers. "But none of them had sports experience, and I thought, 'Jeez, this is like starting from scratch. They may be able to run a business, but what do they know about sports?'"

At some point, McNall called Stern and asked for a meeting. They spoke over breakfast.

"I said, 'David, I want you to become the commissioner of the NHL. We'll double your salary,'" McNall remembers. "And he said, 'Oh, my God. I just really can't leave the NBA.' But he was the god of commissioners in those days, as you probably know, so I thought, 'Let me get the best. I got Gretzky. Maybe I can get the best commissioner too. Why not?' So, anyway, he ends up saying no, but he said, 'I'll tell you what? You can speak to Gary Bettman.'"

Bettman was the No. 3 executive at the NBA behind Stern and deputy commissioner Russ Granik. Since joining the NBA in 1981, he had helped transform the league from a struggling organization into a model one. His experience included everything from the salary cap to labor negotiations to TV contracts to licensing to marketing.

McNall spoke to Bettman alone first.

"I realized he is the perfect guy," McNall says.

The only problem, McNall says, was that some would view Bettman as a basketball guy.

Bettman grew up going to New York Rangers games, had hockey season tickets and played pickup hockey in college at Cornell, and went to NHL games as a fan afterward. Still, he would be coming into the NHL from the outside.

By late November, the list of candidates was down to four or five. The search firm and the executive committee held interviews at the Waldorf Astoria in New York one day, and Bettman was the last to go in the late afternoon.

"We had good candidates, but when Gary came, boy, it was like …" Corey remembers, trailing off, then laughing. "I would call it an explosion of ideas. He was dynamite."

Corey says Bettman showed enthusiasm and knowledge of each aspect of the sports industry. At the same time, he didn't tell the governors what they wanted to hear to try to get the job. He wasn't an expert on the NHL specifically, and if he didn't know something, he didn't pretend he did. He was all business.

"He gave us the real facts, no BS," Corey says. "He doesn't fabricate] an answer. The guy just tells us, 'I don't know. I have to check that.' I love it."

Bettman felt the title of commissioner was important for two reasons:

"One, I wanted to make sure as I was attempting to modernize our operation that I had the same powers that the other three major commissioners had, and obviously I was very familiar with the NBA's," Bettman says. "And two, I wanted it to be a signal that it was going to be different. I wanted it to be an internal and an external signal that we were moving in a different direction. It wasn't going to be the same old, same old."

The committee was unanimous that Bettman could take the NHL to the next level.

"This was the job not only of Gary but of the full League, but you need a leader," Corey says with a laugh. "When you meet with owners, it's not an easy job. Everybody has a say. Everybody thinks they're very sharp. Everybody would like to do something differently. You need somebody to say, 'Well, calm down, everybody. This is the line we want. This is where we want to head. This is our program, this is our plan, and we're going to achieve that this way.'"

Bettman remembers heading out the door after the interview and the recruiter from the search firm saying something like, "That was quite a session." About an hour later, he received a phone call from the recruiter. The committee was offering a three-year contract.

Everyone got a taste of Bettman the negotiator.

"I said, 'Thank you. That's very nice. But I'm not prepared to take the job on a three-year contract,'" Bettman remembers. "It had nothing to do with the compensation. I had a great job, and I didn't want to be worrying in my early 40s about what was going to happen in three years.

"I said, 'It's got to be five years so I can get things up and rolling.' And he said, 'But they're offering three.' And I said, 'Thank you. But I'm not taking a three-year commitment.' He said, 'Let me call you back.' He called me back in five minutes and said, 'You've got five years.'"

Bettman didn't budge with other owners afterward, either.

In his Hockey Hall of Fame induction speech on Nov. 13, 2018, Bettman told a story about a phone call he received after his interview from Chicago Blackhawks owner Bill Wirtz, McNall's predecessor as chairman of the Board of Governors.

"He had very, very, very strong opinions about everything, especially revenue sharing, which he vehemently opposed," Bettman said in his speech. "Before deciding whether to support me, Bill wanted to know my position. We had a very brief conversation, and I told him my view. Suffice it to say, he voted for me, anyway. …

"The most important rules for me in working for ownership have been: You must be open. You must be transparent and thorough. You must make decisions to the best of your abilities and for the right reasons, not political reasons. And you must always tell people the truth, even if they don't want to hear it."

[Watch: Youtube Video

Jacobs says that's how Bettman earned, and continues to earn, the confidence of the owners.

"He maintains a dialogue," Jacobs says. "When you're in front of somebody like this, it's hard to develop a negative approach to him. Even if you don't like what he's done or you wish he'd done it differently, you still respect him."

In early December, several media reports identified Bettman as the likely choice. A Toronto Sun headline said, "NHL has found its man." A Toronto Star headline said, "Bettman Mr. Right for NHL."

"They're getting the most valuable person in hockey since Wayne Gretzky," Milwaukee Bucks vice president of business operations John Steinmiller told the Boston Globe. "That is not overstating the case. He is what the NHL needs at the present time."

\ * * * *

The Breakers is from another time.

The resort's website says it was founded on the sands of Palm Beach in 1896, right at the breakers, where the waves crashed and sprayed.

The current building was designed by the same firm that created the Waldorf Astoria in New York, and it was modeled after the Villa Medici in Rome. Since it opened in 1926, it has hosted a who's who: Rockefellers, Vanderbilts and Astors; Andrew Carnegie and J.P. Morgan; heads of state and NHL owners.

Its ideals are "unapologetic luxury, seaside glamour and world-class service."

The NHL held meetings there from Dec. 8-11, 1992, culminating with annual croquet, tennis and golf tournaments; a cocktail reception; a showing of a Red Wings-Flyers game on ESPN; and a dinner dance.

It was at The Breakers that the League broke from the past.

The night of Dec. 9, Jacobs hosted a dinner party at his nearby home. Bettman says it was so he could meet the owners he hadn't met yet. Jacobs says it was a celebration of his hiring, which was all but official.

"Quite honestly, [McNall] ran the process very much, and we all got behind him," Jacobs says. "There was nobody that I would say that was close to Gary in competency or in background or enthusiasm or energy."

The NHL awarded expansion franchises to Anaheim and South Florida on Dec. 10. The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim and the Florida Panthers would join the League in 1993-94, bringing it to 26 teams and further expanding its footprint. Each team would pay a $50 million expansion fee, $600 million less than the Seattle Kraken would to enter the NHL last season.

David Poile remembers being the first person at the meeting on Dec. 11 specifically because he wanted to meet Bettman.

"What's bigger in the NHL than hiring the new commissioner?" says Poile, then the general manager of the Washington Capitals, now the GM of the Nashville Predators, a team that wouldn't join the NHL until 1998-99. "This is not a two- or three-year position. This is a person that's going to define your sport, your popularity, your revenues, everything. This is the most major decision that a sporting league can make."

The Board of Governors met in the Starlight A Room in the late morning.

According to the minutes, Stein reported the governors could elect a commissioner but would need to amend the constitution to grant him powers. McNall reported that the search firm and the committee unanimously recommended two candidates: Stein and Bettman. The committee members each gave his impressions of the candidates and made his recommendation.

Then Stein withdrew from the race. He said support appeared to be divided, and he wanted the Board to be unified in the interest of the League.

Eventually, Bettman stood in front of the Board of Governors.

"It was almost rubber-stamped," McNall remembers. "He came in. He introduced himself. He spoke a little bit. There were some questions, which he handled, of course, very well. And then the vote came. It was unanimous. It took, you know, five minutes."

Upon a motion duly made by Capitals owner Abe Pollin and seconded by Wirtz and the committee, it was unanimously resolved that Bettman be, and thereby was, elected to the office of commissioner of the National Hockey League effective Feb. 1, 1993, to serve for a period of five years from such date.

"I don't remember a standing ovation, because in fairness to everybody there, none of us knew Gary Bettman, including Mike Ilitch, other than that he had interviewed him with the committee," says Red Wings senior vice president Jimmy Devellano, then the Detroit GM. "We didn't know him. What we knew was that the NBA had passed us. …

"He had worked under David Stern. Stern probably at that time had seemed to be the most up-to-date commissioner, so to speak. He was highly, highly regarded, and I think [the committee] felt a certain comfort level that Gary had worked at David Stern's side."

Poile remembers a wait-and-see attitude too.

"You're bringing in a young guy from the NBA," Poile says. "He's working under David Stern. Those are good credentials. But it's the NBA. It's not hockey. He doesn't have a hockey background. …

"Maybe not being as worldly as we should be at that time, a lot of people thought it should be a Canadian. He came in with some challenges to overcome publicly."

Bettman told another story in his Hockey Hall of Fame induction speech. Late in the evening after his hiring, he strolled into the bar at The Breakers and was greeted by Brian Burke, then GM of the Whalers. Burke went on to work for Bettman as NHL executive vice president and director of hockey operations from 1993-98, and he is now president of hockey operations for the Pittsburgh Penguins.

"He's known to be quite outspoken and a good friend, but Brian Burke and I were not yet acquainted," Bettman said in his speech. "Brian started the conversation like this, 'Boy, are they going to love you.' I probably said, 'Huh?' But for the purposes of the story, I said, 'What did you mean?' And he said, 'You're an American, a New York lawyer, and you're short and from basketball.' All of that was true. The fact that he would actually say that surprised me."

Bettman said perhaps he's an acquired taste.

He's self-aware and self-deprecating, with a quick wit and biting sense of humor.

"I say to him, 'I get all this credit for getting Gretzky. I don't get any credit for getting you,'" McNall says. "And he laughs and says, 'Because you might get grief from] some people too.'"

\* \* \* \* \*

The first call Bettman made after his hiring was to his wife, Shelli. The second was to Stern. The third was to Bob Goodenow, the executive director of the NHLPA, who had sent him a congratulatory note via fax.

Gary Meagher, then NHL director of public relations, now NHL senior executive vice president, communications, remembers handing Bettman a draft of the press release of his hiring. Within 10 minutes, Bettman hand-delivered a marked-up version. Though the press release was only a few paragraphs, he made many edits and went over each of them with Meagher to make sure he understood them, a hint of the attention to detail to come.

Reporters gathered for a press conference and sat in folding chairs. In a dark suit and colorful tie, Bettman sat at a table between McNall and Stein in front of black curtain and an NHL banner. McNall had the jersey folded underneath an NHL cap to his right as they spoke, ready for a photo op.

"I believe that a commissioner has a responsibility to run the game as well as he can for the benefit of everyone -- the owners, the players and the fans," Bettman told the reporters. "The owners are my employer, but the way a league performs well is by making its product as attractive as it can to the greatest number of fans, and I believe that by making this sport as attractive as possible as a sport and as an entertainment product, that we'll be in a position to satisfy all the needs, those of the owners, those of the fans and those of the players as well."

[Watch: Youtube Video

The photo followed, plus another outside on the seawall. The first thing that comes to mind looking back, Bettman says, is that he can't believe he let Meagher stage that. He's being honest. He's also teasing Meagher.

"I haven't held it against him too badly," Bettman says.

Bettman guesses the jersey is in a closet. Neither photo hangs anywhere in his office or home.

"That's not me," he says. "This job, from my standpoint, has never been about me. It's about the League. It's about the owners. It's about the fans. It's about the people that work here and at the clubs. It's about the players. And that may be my legal training. It's always about your client."

Bettman remembers flying home through bad weather the next morning. It was a rough ride, the plane switching airports to find a place to land, but he made it through, foreshadowing the next three decades.

He asked the NHL office to put together a stack of papers for him -- the collective bargaining agreement, the constitution, the bylaws, everything he needed to study. Between Christmas and New Year's Day, he and Shelli took their three children on vacation in Vermont.

"I remember having massive loose-leafs of materials that I was reading when I wasn't skiing or playing with my kids," Bettman says.

He had a massive job ahead of him.

What would the Bettman of today say to the Bettman of 30 years ago?

"Enjoy the ride," he says. "It's going to be challenging, stimulating and intense."

Quoting Thomas Edison, he says, "Vision without execution is hallucination."

"There were things I knew we needed to do to catch up, there were things we needed to do to move forward, and we had to be in a position to execute on all of them," he says. "It always came down to execution and detail."

The results speak for themselves.

"Try to name a change in the last 30 years in hockey that has been more impactful than hiring Gary Bettman, and there is none," Poile says. "There have been some [other big changes], but this is the most significant one."

Says Devellano, who has been in the NHL since starting as a scout with the St. Louis Blues in 1967, "I would say after 30 years Gary has done what he was hired to do, and he's done it pretty brilliantly. I would say as we look back now, I don't remember the League ever being in a better place."