His childhood friend, legendary Chicago Blackhawks goaltender Glenn Hall, once said Fielder was the player all-time NHL point-getter Gretzky most reminded him of. The pair had long remained in touch, sending each other birthday and holiday greetings. When Hall died last month at age 94, it hit Fielder particularly hard.

Fielder had a longstanding fear of flying and famously had not been on a plane since retiring from pro hockey. All his travel since was by car, which limited his ability to get around vast distances. It also kept him from visiting Seattle, Saskatchewan and other places as much over the years, though he remained close with his remaining family and friends in this area.

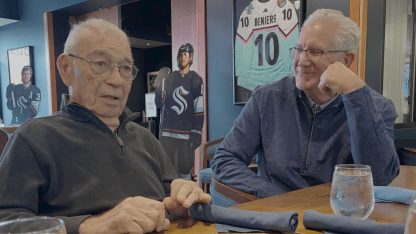

He’d stayed in touch with former teammates, such as Seattle-area resident Jim Powers and his onetime linemate Tommy McVie, who died 13 months ago at age 89 while still living in the Camus, WA home he’d acquired after playing for the Totems. The trio had gone up to Vancouver, B.C. together when Fieder was promoting a 2017 book about his career: “I just want to play hockey: Guyle Fielder: The Unknown Superstar” by author James Vantour.

“I went to Vancouver with him to watch Guyle sign books,” Powers said. “And then we did the same thing here in Kirkland and we met the Seattle Thunderbirds (junior team) together. Those were some good times.”

His limited trips back to Seattle from Arizona had created more than a 1,400-mile distance between Fielder and the city he’d once called home. The Totems ceased operations in 1975 and as time went on, memories of their legacy sharing the city’s sports spotlight with University of Washington football began to fade as the Seahawks and Mariners arrived soon after.

Fielder’s exploits might have remained statistical footnotes had the NHL not made plans to come to Seattle, starting roughly a decade ago with the arrival of Tim Leiweke and his Oak View Group. They announced plans to overhaul Fielder’s former Seattle Coliseum – by then named KeyArena – into what became a $1.15 billion Climate Pledge Arena centerpiece.

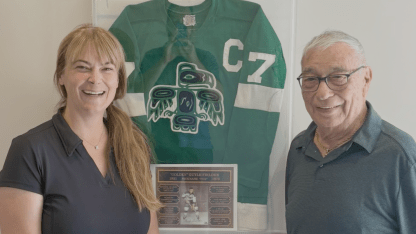

The book about Fielder came out a few months later as memories of what pro hockey had once meant in Seattle were starting to be rekindled. The NHL Seattle group, awarded the NHL’s 32nd franchise in December 2018, invited Fielder up in spring 2019 for a ribbon cutting ceremony in which a replica of his locker was built at the team’s season ticket preview center in Queen Anne.

Fielder, who’d spent his Totem years living – and shooting pool – in Queen Anne, was visibly moved during the ceremony, choking up and fighting back tears.

“I think as he got older, I think the recognition really started to mean something to him,” said longtime friend Doug Buchanan, 75, a former Canadian Olympic hockey team member. “In the early days, he was too busy competing. But as he got older, into his 80s, he got to his reflective stage, and it really meant a lot to him.”

Buchanan first met Fielder in his Williams Lake, B.C. hometown in the late 1960s when the Totems legend bought a home there. He and Fielder would spend time golfing, shooting pool, drinking beer and just getting to know one another despite their 20-year age gap.

“I never even saw him play,” Buchanan said. “He was just a fun guy to be around.”

Buchanan said Fielder was also the most competitive person he ever met, whether on a golf course or in a pool hall. He didn’t need to see him play hockey to understand why he’d succeeded in the sport. Or, to understand the decades spent after his retirement.

“He lived a tight, compact life without a bunch of loose ends to tie up,” he said. “It was his own life the way he wanted to do it.”

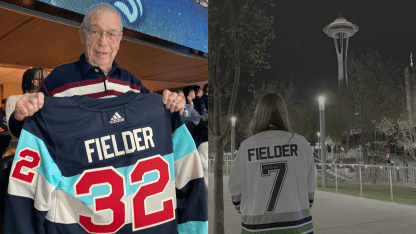

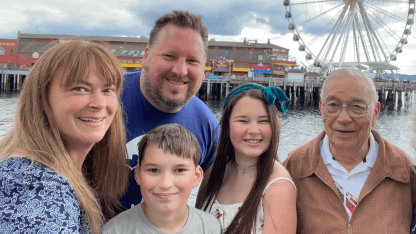

One loose end was tied up for him, when Fielder’s hockey legacy in Seattle was recognized by the Seattle Sports Commission in February 2024. It invited Fielder up to Seattle for its annual Sports Star of the Year gala, giving him its Royal Brougham Sports Legend Award.

He and Johnson made the nearly-3,000-mile round trip drive together.

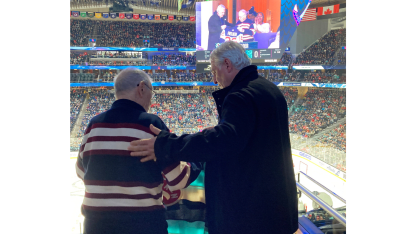

Two days later, Fielder attended his first Kraken game at Climate Pledge Arena with his former Red Wings the visiting team.

“What a beautiful building – oh my word!” Fielder said, glancing around. “It’s awesome.” He watched the game from the owner’s suite and was introduced on the twin scoreboards to raucous applause as then-general manager and current Kraken president Ron Francis gave him an honorary jersey.