“It’s all up here,” Forslund said, pointing at his forehead. “All committed to memory.”

But he’ll nonetheless meticulously jot down notes about both teams two, even three games ahead of time, the exercise ingraining details in his brain as part of his preparation ritual. He’ll watch video clips of all nightly NHL games, seeking line combinations, tendencies, and player numbers to practice the game call in his head.

Forslund, on Thursday night, begins his fifth season calling Kraken television broadcasts, doing so now on the team-run Kraken Hockey Network. But, Forslund’s second foray of breaking in fans in a new NHL market remains relatively nascent compared to his journey getting here; borne of learning on the fly but also dealing with the unexpected.

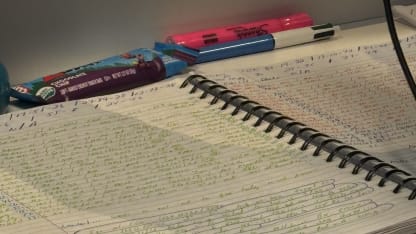

“I write all of this down, but in the end, I share maybe three percent of it with the audience,” Forslund said, pointing at dozens of notebook entries in multicolored ink containing words, numbers, and symbols across perfectly lined columns. “When I was young, I was going to prove everything that I knew and prove I’d come prepared. But I later realized it’s more palatable for fans to hear you describe the game than bog them down with all these stats and endless talk about points streaks and things of that nature. Now, if I give them one salient point they can take away in a game, then that means something.”

He paused before continuing. “But these are still important for me because if something happens with a player and I need information, I know it’s there. There’s a comfort in that.”

Preparing for the unexpected helps Forslund feel confident and be himself on-air, a commitment to authenticity he long ago deemed vital. Just as he learned from his career’s outset about how the unexpected can blindside.

He’d collected his first broadcasting paycheck in January 1985 at age 22 after working a game for the AHL team in his Springfield, Mass. hometown, about 90 miles outside of Boston. Forslund brought it home that night to show his father, Ralph, at his parents’ house, where he still lived, but had gone out beforehand with his then-fiancée-now-wife Natalie, so dad was asleep when he arrived.

Forslund was awakened early the next day by screams from his mother, Yolanda. His dad, a 59-year-old former U.S. Marine corporal in World War II who’d started his own automotive paint business, had suffered a heart attack in his sleep.

Forslund was certified in CPR and tried frantically to revive him. But his father died in his arms.

“He was my best friend,” Forslund said.

◆◆◆

The “shattering” loss sent Forslund into a depression, though he continued calling Springfield AHL games on the radio and television after taking a week off. He worked through his grief, using his fledgling career in hockey as a tribute to the man who’d introduced him to the sport.

They’d been at his aunt’s house for Mother’s Day on May 10, 1970, when Forslund, who’d just turned 8, watched on TV as Bobby Orr scored in overtime to deliver the Bruins’ first Stanley Cup in 29 years. Dan Kelly on CBS called that iconic Boston Gardens goal, and it “sparked” something inside Forslund that made him want to do that job.

“I didn’t know how I was going to do it,” Forslund said. “But that’s where it all started.”

Forslund and his father, the next season, turned down the sound to televised Bruins games. From there, Forslund did play-by-play while his dad was the color commentator. His dad’s buddies showed up to watch them.

His father often worked long hours at his paint company, and so their nighttime commentary was how they bonded. On weekends, they’d attend Springfield Indians AHL games together.

Forslund supplemented their makeshift living room broadcasts with information from player notes he’d write down beforehand. At first, it was so he could match players to their numbers, as there were no names on team jerseys back then.

“The one thing God gifted me with was a photographic memory,” Forslund said. “I always was a good memorizer. And I could also get up in front of my class and speak. And those two skills gave me what I needed for the foundation of this job.”

Forslund began developing his broadcast cadence listening to Bruins play-by-play man Fred Cusic, then Danny Gallivan and Bob Cole on a local station carrying Hockey Night in Canada’s feed from CBC. Father and son continued home broadcasts for years ahead of Forslund attending Springfield College and later pursuing a master’s degree in sports management at Adelphi University in New York.

His parents were optimists, encouraging Forslund’s sports dreams. His mother got on Forslund about not reading enough, so he soaked up as many hockey history books as he could by renowned author Stan Fischler and others.

While getting his master’s degree in New York, Forslund had been a prep school baseball coach on Long Island and was offered a full-time job there. Forslund had played baseball throughout his youth, sometimes on teams coached by his father, so the offer intrigued him.

But he had to do a sports internship before graduating. Though he hadn’t majored in broadcasting, the news director at his college TV station heard a tape of Forslund voicing over the 1981 Super Bowl for an elective class and encouraged him to pursue that field. Forslund sought an internship that did that, becoming a finalist for a West Point job hosting a coach’s show ahead of the 1984 Army-Navy football game.

But Forslund didn’t get it. Instead, an acquaintance in Springfield who knew the AHL team’s owner arranged an interview with the hockey club. Forslund got an unpaid internship that included part-time broadcast work as a color commentator. Within months, it morphed into a full-time gig. That’s when Forslund brought his first paycheck home to his father.

But now, his father gone just as the career he’d fueled within his son was starting, Forslund found himself on long, lonely team bus rides to opposing cities, pondering what it all meant.

Forslund’s father had been a prisoner of war in Japan and received a Purple Heart for combat wounds suffered while fighting with the USMC Sixth Division in the Pacific. But he hadn’t let it darken him outwardly. Instead, he’d pushed beyond wartime trauma, married his childhood sweetheart, and moved back home to Springfield to raise a family. He had a “Hey, hey, whaddya say?” greeting for anyone he’d meet the first time, or while coaching Forslund’s youth baseball teams to keep things upbeat.

One year after his father’s death, Forslund, still struggling with it, had become Springfield’s play-by-play man and used his father’s expression on-air to celebrate a goal. And he continued using it as his career began taking shape.

◆◆◆

For a kid from New England, the Hartford Whalers were as good as the NHL got beyond Boston. The Whalers joined during the NHL’s 1979-80 merger with the World Hockey Association and in 1991 hired Forslund as public relations director. Forslund, at the time, would do anything for an NHL jump, and the job – though not his favorite – did include radio color commentary work alongside longtime Hartford play-by-play man Chuck Kaiton.

Forslund’s final years in Springfield had helped his booth confidence enough to win the Ken McKenzie Award for the AHL’s top broadcaster/publicist in 1989. Springfield’s coach, former NHL player Jimmy Roberts, had even arranged for him to meet boyhood idol Kelly – whose call of Orr’s 1970 Stanley Cup overtime winner sparked Forslund’s initial play-by-play interest.

“Dan took the time and gave me the advice to never ‘sell down’ a moment,” Forslund said of Kelly. “In other words, even if you’re working for a team and the other team scores, don’t downplay the goal-- elevate it.”