Shirley Walton Fischler wasn't asking for very much; just the right to earn a living.

But they wouldn't let her.

This was 1971 at Madison Square Garden. Shirley was assigned to cover the playoff between the Rangers and Maple Leafs. At the time she was co-manager of the Toronto Star's New York Bureau; a working journalist.

Her other employer was a prestigious Ontario daily, the Kingston Whig-Standard. The sports editor had known Shirley through her previous writings and felt she would do justice to the playoff story.

Only one problem, Shirley forgot to read the fine print on the press ticket which all writers received for admission to the games.

The fine print read, Ladies not permitted in the press box. There it was in plain English and had been for decades.

"Frankly," Shirley allowed, "I had no idea this was the case."

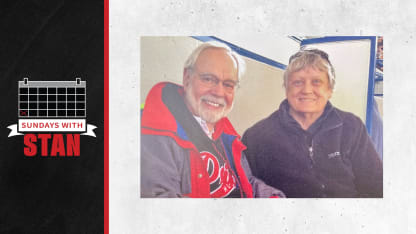

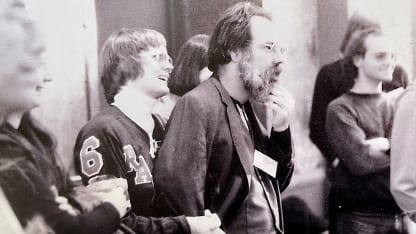

SUNDAYS WITH STAN: Unsung Pioneer of Women Hockey Journalists

Stan Fischler writes about someone very close to him who pioneered hockey reporting for women, Shirley Walton Fischler

Blithely, Olivetti typewriter in hand, she climbed up the long set of stairs leading to the Garden press box. Former Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton was right behind.

And a good thing, too, because eventually, Shirley would need witnesses. Bouton was covering the game in his post-baseball gig as ABC-Television sportscaster

When Shirley arrived at the gate to journalists' row, the formerly-friendly attendant shook his head. "Sorry, M'am, no ladies allowed in here. Find a place somewhere else."

He wasn't kidding either. As a rule The Garden was a hospitable place. Shirley had been to dozens of games there and knew many ushers, players, and even the Zamboni driver.

But the press box was for men only and the male writers who populated it monitored their sanctum like guards policing the Hope Diamond.

The dozen or so writers from the Daily News, Times, Associated Press, and Newsday, among others, all knew Shirley and had been -- until that fateful encounter -- friendly with her.

But on this night, they wanted no part of anyone breaking the barrier to their inner sanctum. No way.

"What could I do?" Shirley would later testify before the New York City Human Rights Commission. "Aside from my typewriter, I had a pile of stats

and newspapers and no place to put them. I was a non-equal."

She eventually found an empty seat 'way high up in the cheap seats and covered the game as best she could. After filing her story, she returned home and asked me what to do.

Knowing that she was a fighter, I suggested she contact a relatively new organization, the New York City Human Rights Commission. She agreed, got up early the next morning, hustled downtown, and won a hearing.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, the Commission chair-woman, was impressed with her credentials. Who wouldn't have?

By that time Shirley had been co-editor of Action Sports Hockey magazine, produced and performed in her own weekly show, "Young Side" on the ABC Network -- her next-door neighbor at ABC was Howard Cosell -- and was writing a hockey book.

She had published stories for the Toronto Star including the last 1971 interview with Hall of Fame goalie Terry Sawchuk. It appeared in The Star and received continent acclaim.

"Eleanor Norton gave me a good listen," Shirley recalled. "She checked with the Commission legal staff and felt that I had a case. They contacted the Garden people and ordered them to present their side."

Unknown to Shirley, her attempt to crack the Rangers anti-female edict ignited a fury of indignation among the male writing fraternity. Among those manning the barricades were previously close friends of ours.

Mel Woody, who covered the Rangers for the Newark News, had been a pal -- and colleague -- of mine for years. He was among the Anti-Shirley leaders. End of friendship.

Ditto Hal Bock of The Associated Press. He and I had co-authored Rod Gilbert's autobiography, "Goa! My Life On Ice." We couldn't get any closer than that. (We didn't talk for a good ten years after.)

"At this point," Shirley related, "things began to get silly. Men who had been colleagues of mine began ranting that they would quit the business' rather than sit with a woman in the press box."

Others pointed out that it would be inappropriate for a female to sit with the male media because she might hear language that was unsuitable for "a lady's ears."

A colleague and even closer friend, Gerry Eskenazi of the New York Times, chose to ride the fence. When he turned away from supporting Shirley, I had a queasy feeling that The Garden would win the case.

As it happened, only one journalist went to bat for my wife; a young columnist for the New York Post, Neil Offen. He wrote a passionate piece in his paper and it helped challenge the Garden opposition which by now had become formidable.

Rangers general manager Emile Francis firmly lined up with the club's publicist, John Halligan, and he was supported by club president Bill Jennings, himself a powerful attorney.

Shirley described the clashes at the hearing as "vitriolic" but she held her own and won her case. She was able to fulfill her assignment and finish covering the playoff series.

Just for the record, The Commision ruled that sex, race and/or religion woud have absolutely nothing to do with access to the press box.

It was not an easy victory. Shirley was emotionally spent from the ordeal but returned to her work while raising her two children. She opened a women's book store in Greenwich Village and continued breaking ground.

In 1973, she was hired -- along with me -- as tv analyst for the World Hockey Association's New England Whalers. It was another landmark accomplishment.

That marked her as the first female tv hockey commentator; plus we became the first husband-and-wife team to work pro hockey games on television.

"Shirley did an excellent job," said Howard Baldwin who ran the Whalers and would become WHA president. "She knew her hockey as well as the men competing against her."

One might wonder why Shirley Walton Fischler did not obtain wide acclaim for her significant work on behalf of the women's movement.

"My Mom never was interested in personal publicity," says her younger son, Simon. "She never made a big deal about her victory. She was interested in the cause and this particular cause was close to her heart."

It had to do with a woman wanting the equal right to earn her living as a hockey journalist -- and the willingness to fight for it.