When Leon Hayward was eight years old and growing up in Seattle, his mom missed the signup deadline for playing soccer as part of programming at the Wallingford Boys and Girls Club. Let's first make it clear: All is forgiven, Mom.

"I was driving long-distance to my job," says Lori Richardson, who raised Hayward as a single mom. "I really needed Leon to be in the after-school soccer program. I didn't know what I would do if he couldn't play."

Love at First Ice

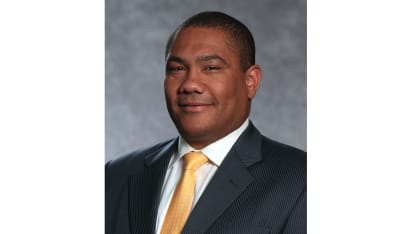

Youth hockey might have started as a second option for Leon Hayward, but the sport swiftly won over the Seattle-raised player who is now one of two Black assistant coaches in college hockey

A woman, overhearing Richardson making her unsuccessful plea with club officials, suggested youth hockey at the Highland Ice Arena in Shoreline as an alternative. Richardson's first reaction? "I didn't want my kid to lose his teeth."

But Richardson reconsidered, driving her son over to the Highland rink. She realized many kids learn how to skate much earlier than eight years old. But her son was undeterred.

"We arrived at Highland and Leon looked out at all the kids skating around," recalled Richardson during a recent phone interview. "He turned to me and said, 'This is what I want to do.' The next thing I know is he is out on the ice on skates pushing around a metal chair."

"I flew around and got around out there pretty good," said Hayward by phone earlier this month during a Friday afternoon before a NCAA Division I game that night between Colorado College, which he serves as assistant men's hockey coach, and Nebraska-Omaha. "Well, I did have zero brakes [not yet learning the hockey stop] but I realized from the first time on the ice that it was so much fun."

So long, soccer. Hayward learned the hockey stop and much more, progressing to play for the Seattle Junior Hockey Association and Sno-King Amateur Hockey Association teams before earning a spot playing for Tabor Academy, a prep school in Marion, MA.

Hayward is no doubt modest. He progressed to play four years at Northeastern, one of college hockey's elite programs that is part of the annual famed Beanpot tournament of Boston-based NCAA teams, then professionally in the East Coast Hockey League (ECHL) and American Hockey League (AHL) from 2001 to 2007.

"I played in 100 AHL games, no one would have thought that," said Hayward, who notched 85 goals and 88 assists for 173 points in 358 professional games.

Hayward decided to go pro in part to chase a team championship, something he had not accomplished in youth, prep and college hockey. The goal became reality in 2005 when the Trenton Titans won the ECHL's Kelly Cup, a steeper challenge than most years because the NHL was in a labor lockout and many NHL-caliber players kept their conditioning playing for AHL teams, pushing usual AHL players to return to the ECHL. Hayward was named MVP of the 2005 postseason run, scoring six goals and assisting on five more, plus adding a physical presence to the Titans' forward lines with his two-way play and 32 penalty minutes.

One of Hayward's ECHL championship teammates was Andrew Allen, the Kraken's pro scout specializing in goaltenders, the position he played for Trenton. Like many championship teammates across all levels of hockey, the two men have kept in regular touch. Hayward said, "Andrew should have been named MVP instead of me."

Allen was having none of it during a phone call this week: "Leon was really good and scored a huge goal at the right time for us. We won the first two games of the final series on the road, then came home for three games in the 2-3-2 setup. We lost Games 3 and 4 and fell behind 2-0 after two periods. Early in the third period, Leon jumped out of the penalty box, found the puck and buried a backhand deke on a breakaway. We then scored about five goals in four minutes and won Game 6. He changed the whole momentum of the series.

"Leon is the type of guy who lights up a room when he walks in. He is a great recruiter paired with deep hockey knowledge. I was a serious guy. Leon was good for me in that way, keeping me loose. When we were celebrating the championship on the ice, he said, 'Now I can talk to you again! You were playing so well I didn't want to mess that up!' "

Hayward caught the coaching bug during his last pro season as a player. As a veteran he helped a first-year group player achieve a quicker release on shots. The teammate scored a goal in the next game and Hayward realized how excited it made him feel, something he relives every practice working with Colorado College players on a roster dominated by freshmen.

The school's head coach, Mike Haviland, coached that Trenton championship team and went on to win a Stanley Cup ring with Chicago in 2010. He hired Hayward in 2017. Hayward is one of two Black assistant coaches in NCAA Division I hockey, along with one Black head coach in Division III women's hockey.

"Coaching at the college level is a little bit of everything," said Hayward. "There's the recruiting aspect and teaching players. I love being on the bench too. I have spent 25 summers with Paul Vincent at hockey camps in Massachusetts]. I've watched and worked with hundreds of players, understanding how they get better, if they want to get better. It's a continuous process, even as players turn 21 or 22 or 25. If they believe and coaches move with them, players will get better."

There's so much more to report about Hayward, including

[his candid, powerful tweet regarding the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer last spring

.

Plus there's his years as a stick boy for the Seattle Thunderbirds, his mom billeting T-Birds player Paul Vincent Jr. (which led to decades-long mentoring from Paul Vincent, a famed hockey development coach and current hockey skills director with the Florida Panthers), Lori Richardson serving on the Sno-King board, Hayward and his mom living in the Victory Heights neighborhood ("three minutes from the new training center!") and Hayward's 10-year-old son idolizing New Jersey defenseman P.K. Subban. But let's end this story and Black History Month (but not our BIPOC reporting, which is year-round) with perspective from a Black hockey player and coach with Seattle roots.

"Growing up in Seattle, the diversity in public schools was awesome and ahead of the curve," said Hayward, 41. "When I went out to the East Coast, I realized, 'man, there are a lot of people who think like this' [racist leaning]. There were definitely racial incidents during my Seattle youth hockey days, but my teammates were even more offended than me and went after opposing players harder than me. My coaches were really standup about it too. In those days, it was hard for a Black player to say much. I appreciate how my teammates and coaches stood with me."