TORONTO -- The morning newspapers were spread out Friday morning in front of Dave Keon, who sat one table from the very back of a downtown breakfast nook which he frequents from time to time when he's in town.

Tossed aside was a tabloid splashed with his photo, an image of Keon standing beside the life-size bronze statue of himself that had been unveiled 14 hours earlier at Toronto Maple Leafs' Legends Row outside Air Canada Centre.

Dave Keon has monumental weekend in Toronto

Maple Leafs legend reflects on statue unveiling, number retirement in exclusive talk with NHL.com

What caught Keon's attention was a national broadsheet with a story on iconic singer Bob Dylan, who the day before had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

"I met Dylan once," Keon said, and of course he had. Name an important public figure of the 1960s or 1970s that Keon hadn't met when he was a star, then the captain of the Maple Leafs.

"He was at Maple Leaf Gardens (in the early 70s). I was going to present one of my Leafs sweaters to Robbie Robertson of The Band, who were opening for him. So I came backstage at intermission, saw Robbie, and there was a small fellow wearing a hat sitting in the corner."

A tight grin was working at the corners of Keon's mouth.

"It was Dylan, and I was brought over to be introduced to him," he said. "I guess I met him, though they told me I wasn't supposed to look at him."

Breakfast soon arrived, a healthy blend of granola, yogurt, fruit and a muffin, and Keon, 76, nattily dressed in a crewneck sweater and slacks, was digging in when a gentleman appeared.

"Dave Keon, right?" the man said, replied to with a nod and a handshake.

"I'm Alfred Apps. I'm an Apps."

This would be the wide-branched Canadian family whose roots include 1930s and 1940s Maple Leafs icon Syl Apps, his son, Syl Apps Jr., who would play in the NHL, grandson Syl Apps III, a minor-leaguer and Ivy League hockey star and granddaughter Gillian Apps, a three-time Olympic women's hockey gold medalist for Canada.

"Which Apps are you from?" Keon asked.

"I belong to all of them," Alfred Apps replied, then excused the interruption and exited with a smile that lit up the morning, delighted for this half-minute-long accidental meeting with one of his heroes.

This will be a brief but hectic and, indeed, monumental visit to Toronto for Dave Keon.

His statue was unveiled on Legends Row with those of fellow Maple Leafs legends Turk Broda and Tim Horton. After breakfast, he would walk to the NHL offices, attached to Air Canada Centre, and sit for a video profile interview, after which he would casually go for an unadvertised walk through the Hockey Hall of Fame's Maple Leafs Centennial Anniversary exhibit, visiting with a group of family and friends.

© Mark Blinch/Getty Images

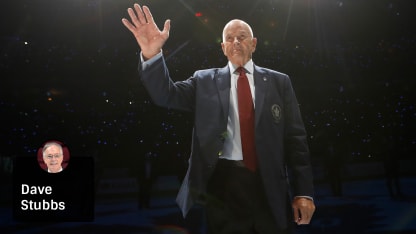

At a news conference that afternoon, Keon would be introduced as the No. 1 Maple Leafs player of all time, topping a list of 100 voted by a selection panel and an online ballot of fans.

And then Saturday evening, la pièce de résistance: Keon's No. 14, conspicuous by its absence for decades following his glorious, trailblazing Maple Leafs career, would be moving into the rafters of Air Canada Centre, retired from service forever, before Toronto's home-opening victory against the Boston Bruins.

Some thought the day of reconciliation between Keon and his team would never come, the player among that group.

More than 40 years after his last game for this franchise, Keon remains larger than life to a generation of fans. On Saturday, his number was retired alongside those of 16 other former players whose "honored" numbers were upgraded by the team to fully retired. So now Keon will become a research project for younger fans; if they dig a little, they'll learn what a giant talent and inspirational leader this man was, and remains, to the Maple Leafs.

Keon's falling out with the Maple Leafs dates to the mid-1970s, when then-owner Harold Ballard dismissed his sparkplug leader's 15-year contribution to the team and for all intents and purposes exiled him to the World Hockey Association, refusing to release him to play elsewhere in the NHL without massive, unreasonable compensation in return.

Keon also had an issue with the Maple Leafs' refusal to retire sweater numbers. Until Saturday, the team hung banners of its greatest stars in the rafters of Maple Leaf Gardens and, later, Air Canada Centre, but allowed their numbers to be worn by an endless run of other often average players, many of whom were merely passing through Toronto.

"I was hoping that they'd retire Teeder's number while he was alive and aware of what was going on," Keon said of late former captain Ted "Teeder" Kennedy. "They didn't, for whatever reason, and that was really disappointing. Apps and Charlie Conacher and Kennedy and Broda… all those guys who played in the 1930s and 1940s and built this team. In some ways, the Leafs have treated them like they don't exist. I don't really know what honoring a number really means."

(On Saturday, following the number retirement ceremony that had remained a secret until the final moment, Keon quietly pulled me aside with an apology: "I knew this was coming tonight," he said with a tight smile, "but I couldn't tell you.")

© Kevin Sousa/Getty Images

For years, Keon had resisted Maple Leafs overtures that he should return to the family, although he did come to Toronto a few times for celebrations of teams on which he had starred. A fiercely proud man with a wide stubborn streak, he merely shrugged and replied that he'd moved on with his life and was not interested in any individual recognition. His No. 14 wasn't even among the "honored player" arena banners.

But the arrival of Maple Leafs president Brendan Shanahan in April 2014 began to thaw the ice.

"Is this the right time to rejoin the Leafs family? I don't know. Maybe," Keon said over breakfast. "Brendan called me a year ago this September, said they wanted to put me on Legends Row and asked if I'd think about it. I did for a day and I called him back. I thought it would be good. I thought my grandkids would enjoy it.

"It was a great evening," he said in reflection of the unveiling. "I thought the Leafs did a great job. I was really happy with the way everything turned out. I have a lot of people here for the weekend, and they enjoyed it."

Indeed, the Keon clan numbered about 20, including his wife, Jane, four children and their spouses, his brother, two sisters and seven grandchildren whom he introduced with chest-swelled reference to their academic achievements, plus another dozen or so friends who had come from far and wide.

"Thank you for showing me that life is not always black and white, but quite a bit of grey," Keon said to his wife at the unveiling ceremony, an interesting look into his soul.

Last January, 30 years after he had been inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame, Keon stepped onto Air Canada Centre ice with members of the families of Broda and Horton for the announcement that the three would be joining Legends Row in October, on the eve of the team's 100th season. Finally, on Saturday, his banner was hoisted with fanfare and emotion alongside fresh ones celebrating 18 other Maple Leafs legends.

Long a stickler for detail, Keon had taken an active role in the production of his 1,000-pound statue, visiting the Chicago-area studio of sculptor Erik Blome.

"Dave taped the stick that he holds in the statue," Blome's wife and sculpting partner, Charlotte, said the day after the unveiling. "It had to be done just so."

"And his skates, which are largely hidden behind the boards where he stands, had to be laced precisely the way he used to do them, the tongue positioned exactly right," Erik Blome said, laughing.

Keon considered this input, saying, "Yes, I made a few suggestions. I had too much hair originally, and I wanted a few changes around my chin. There was some stuff with the stick and a little with the skates, which I guess you don't even see."

It's hardly a surprise that Keon had such a hand in the design of the statue. He was a man of firm routine in his playing days, putting 14 revolutions of tape at the top of the shaft of his stick.

Never 13, never 15.

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

"A superstition?" he asked. "Maybe a little. But doing it that way seemed to work for me, so there was no reason to change."

Keon was happy to talk about his recent induction into the Quebec Sports Hall of Fame, a native of the hockey hotbed of Rouyn-Noranda, the son of a miner and a school teacher.

"That was nice," he said, having flown into Montreal from his home in Florida for the ceremony. "A lot of people in Quebec don't think I was born there. Rouyn is in Quebec and Noranda is in Ontario, but they're 200 yards apart."

At 5-foot-9 and 165 pounds - he looks to be at his playing weight still - Keon grew to become the best two-way center of his era, a skater with explosive power who made space for himself on the rink, then found his linemates with passes not to where they were, but where they soon would be.

He wasn't popular with everyone in the dressing room, not that he tried to be. His resolute goal was to win hockey games, and he did that with a steely eyed focus and uncompromising sense of purpose that could intimidate both opponents and teammates.

Keon won the 1961 Calder Trophy as the NHL's rookie of the year, led his team to four Stanley Cup championships in the 1960s, earned the Conn Smythe Trophy as the most valuable player of the Stanley Cup Playoffs in 1967 -- Toronto's most recent title -- and in 1962 and 1963 won the Lady Byng Memorial Trophy as the League's most gentlemanly player.

If Keon was as rugged as they came, he earned a ridiculous total of 117 penalty minutes, and only one fighting major, in 1,296 career NHL games with Toronto and, for his final three seasons, the Hartford Whalers.

© Melchior DiGiacomo/Getty Images

His playmaking skills were exemplary, and he'd have scored many more than 396 NHL goals (498 including his WHA output) if he hadn't been assigned to check the opponent's best line, adding 590 assists to his NHL balance sheet.

"I might have been a different player had I been given a few more inches and another 20 pounds," Keon said with a laugh. "I might not have had the quickness. I never thought my size was a problem. Everybody has attributes that other people don't have. You have the exceptions: Jean Béliveau was big and agile and coordinated, Frank Mahovlich and Gordie Howe were the same way. But most of the guys who were that big weren't as coordinated."

Keon's place in hockey history was cemented three decades ago with his induction into the Hall of Fame, a few rink-lengths north of where his statue now stands and banner now hangs.

Before Saturday's ceremony, his son, David Jr., said that his stoic, stiff-upper-lipped father "was about as excited as he gets" about the ceremony that was about to take place. But clearly, Dave Keon was profoundly moved when his No. 14 was positioned in the arena rafters.

He was, and remains, the quintessential teammate, a part of the whole, never bigger than the crest on his sweater or the game he loved with every breath.

"I'm pleased about it, I'm flattered," he said over breakfast about the enduring love extended to him by Maple Leafs fans. "When I left home, I was hoping to play junior and maybe get a chance to play pro. I was fortunate to play with and be coached and guided by good people, who made me a better player. I'm happy with the way it went."

The fan mail still arrives, from people who never saw Keon play.

"A letter might say I was their father or grandfather's favorite player, so they've looked me up and they'd like a picture or something signed," he said.

"I hope the majority of Leafs fans got their love of the team from their parents and grandparents, and hopefully they will get to see us be competitive and get some wins, because their parents and grandparents saw us win. Hopefully, that happens for this generation so they can pass it on.

"And I'd like to think that today's team will learn what has to happen for them to win. It's like this," Keon said, his finger and thumb a half-inch apart, "the difference between winning and losing."

© Mark Blinch/Getty Images