“Colton kind of led the way for Chandler down his hockey path,” Stephenson’s father said. “Everything they did hockey-wise, he would do first, and then Chandler would follow.”

But childhoods don’t last forever, and the attempted climb into hockey as adults wasn’t always the storybook parents' dream of. In older brother Colton’s case, he’d suffered his fifth concussion by age 18 and made a life-altering decision at 19 to quit the major junior ranks rather than continue playing with the Edmonton Oil Kings of the Western Hockey League.

“That was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever dealt with,” Curt Stephenson said, his voice cracking with emotion.

He and Colton had plenty of discussions before his son walked into the Edmonton general manager’s office and told him he had to quit because he wanted to be able to remember the names of his children by the time he was 28.

“We’d talked about it a lot before that,” his dad said. “There were a lot of tears. Just like I’m having right now.”

Plenty of professional counseling as well. Colton cried all the way home from that meeting with his GM and struggled for years to adapt to a post-hockey world. It wasn’t until his 30s that he finally summoned the courage to ask his younger brother whether he could have made the NHL as well, and was told they were equal in talent.

“I didn’t want to ask him when I was still of age to chase it,” Colton said in an interview last year. “Because from my neck down, I’m perfectly fine and perfectly healthy. And me and Chandler? Same build, same body, and everything. And I’m not injured. I have a body that could probably practice and play. But I just don’t have the brain that can handle it anymore.”

All the while, younger brother Chandler kept rising through hockey’s major junior and then professional ranks, slowly at first as an AHL minor leaguer before breaking through full-time with the Caps that 2017-18 championship season alongside assistant coach Lambert.

As a father, Curt Stephenson was ever mindful of his son Colton’s dashed dreams whenever celebrating Chandler’s on-ice successes. It helped that both sons were very close. And that each could set aside their own worries and focus on the other’s tribulations; Chandler in helping his brother navigate life after hockey, and Colton, telling his at-times-frustrated younger sibling, a third round, 77th overall draft pick, that years of minor league struggle would eventually pay off with an NHL career. Whenever somebody said something negative about Chandler’s play, his dad said Colton would tell his brother, ‘You’ve got to prove people wrong.’”

That first full NHL season for Chandler, the Capitals beat the Vegas Golden Knights on the road to claim the franchise’s first championship. Stephenson’s dad and brother were both there to see it happen.

“We’re watching them all throw their gloves in the air and skate around,” Curt Stephenson said. “And I remember Colton, he’s standing beside me, and he says, ‘He did it.’

“Like, he was so proud. And I said, ‘You were part of this journey for him. You be proud.’”

Colton’s former Oil Kings GM, Bob Green, agreed to keep him on the WHL team’s roster for a full five years. That way, the league continued paying Colton’s college tuition and allowed him to obtain his kinesiology degree.

“You know how people will sometimes say that hockey’s a cruel sport and you’re just a number or a piece of meat?” his dad said. “Well, it could not have been any better for Colton. Because they appreciated him.”

Colton now runs a training program for a Saskatoon company called Counter Move, geared toward skills development for young hockey players.

As for Chandler, he takes after his father in many ways. While growing up, excelling in youth hockey, he watched his dad invite family friends and even his sons’ teammates over for backyard rib lunches and Caesar salads made with recipes given to him by a restaurateur friend named Peter Rizos. That tradition continues today, with Chandler often cooking for NHL teammates and friends with the same recipes given by his dad.

His father, who’d been a senior league baseball pitcher in Saskatoon, has spent more than 40 years managing a local scrapyard. He tried retiring a few years back, then realized that while he loved it in summer, he hated the lack of activity during long Saskatchewan winters.

“You’re doing a lot of snow shoveling, but that’s about it,” he said.

When the scrapyard’s owner phoned to ask how retirement was going, he told him the truth.

“He asked me whether I’d like to come back and I told him, ‘Absolutely,’” he said. “So, I’m doing the same thing now, but it’s a lot easier because I don’t have to worry about the pressure of selling loads of copper and aluminum, and brass. I just go in and help them out where I can.”

Curt Stephenson feels his work ethic and values, like treating others well, rubbed off on his boys. He still lives in the same two-story, split-level home on the cul-de-sac where his now NHL veteran son knocked on his future Kraken coach’s door for a cookie.

“As good a hockey player as Chandler turned out to be, he’s an even better person because of how he treats others,” his dad said.

Back when the boys were 6 and 8 and dominating their respective youth leagues, a Bauer representative approached Curt and his wife, Bev, offering to sponsor their sons with free hockey equipment. By the time Chandler was 9, he was playing for an elite spring hockey team but also a city-wide squad for players from widely diverse backgrounds and family income levels.

The rep offered Chandler a new line of Bauer Vapor sticks for his entire team and assumed he’d give them to the elite spring squad. But the 9-year-old future Kraken player told the rep he’d rather give the sticks to his city team.

When the rep asked why, Chandler told him, “Because some of the kids can’t afford the sticks. They only have wood sticks.”

His father said Chandler then went around his team’s dressing room gathering everybody’s measurements and blade preferences. Not long after, Chandler gathered his teammates together and took them upstairs, along with their parents, to give them their customized, top-of-the-line graphite sticks with their personalized names on them.

“The parents were crying, and the kids, they couldn’t believe it,” his dad said. “He handed them out to every one of those kids. One of them was afraid to use it because he thought he might break it. He just wanted to put it in his room and not touch it. But I told him, ‘No, you have to use it. That’s why we’re playing hockey, right?’

“It was just heartwarming. And it was all because Chandler said, ‘They can’t afford it.’”

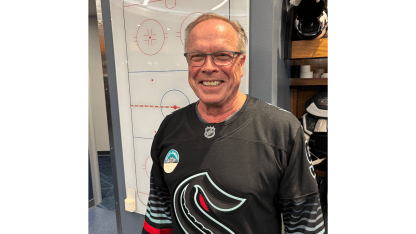

Such memories will keep flowing through his mind this week as Curt visits with his grown son, still forever a young boy to him. He was at Wednesday’s Kraken game against the Los Angeles Kings at Climate Pledge Arena, chuckling when presented with his son’s official bobblehead doll from that night’s team promotion.