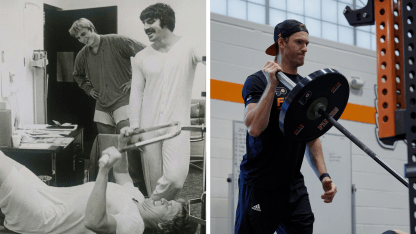

In today's National Hockey League, conditioning standards for players are extremely high. Everything players do in terms of exercise, diet, rest, on-ice workloads and neurological baselines are carefully measured and monitored throughout the season. Team workout facilities such as the Flyers Training Center in Voorhees, New Jersey, are state-of-the-art. Clubs employ not only strength and conditioning staff but also dieticians and sports science specialists. Long gone are the days when, as legendary Pittsburgh Penguins center Mario Lemieux once famously put it, an off-season conditioning plan consisted of little more than "a month before the season, I stop putting ketchup on my French fries."

Then and Now: The Evolution of Training Camp

Strength and conditioning regimens in the modern era have become much more rigorous than those of the past

By

Bill Meltzer

philadelphiaflyers.com

Back in the mid 1970s, the Philadelphia Flyers became one of the first NHL franchises to provide players with off-ice workout facilities at their team's practice facility. A small workout room was created at the Class of 1923 Rink on the University of Pennsylvania. More notably, the Flyers became the first NHL team to adopt the then-trendy Apollo workout equipment line of resistance training devices. With these devices -- pullies, elastic bands,ropes, etc, -- the harder one pulled, the more weight resistance the user received.

However, the opposite was also true. It didn't take long for unsupervised players to realize that using the workout devices didn't have to be strenuous if they weren't trying very hard.

"There were guys who would grunt and pretend like they were straining but they wouldn't be pulling on the devices very hard at all," longtime Flyers broadcaster Steve Coates, a minor league player in the Flyers farm system in that era, recalled with a chuckle.

Once players got on the ice, it was common for them to do some light stretching to warm up. In terms of on-ice drills, players found out on the ice what they'd be doing next. Legendary Flyers head coach Fred Shero enjoyed surprising the players with offbeat drills as well as familiar ones. One drill that Shero introduced -- which is still periodically in use to this day -- is for defenders to hold their sticks backwards with the knob of their stick to the ice and the blade off the ice. The purpose was to open up the lanes for passers and to challenge the defender to take away the added space by their angling.

"Screwiest thing I ever saw. I was thinking, 'How the hell is this going to be useful to us?' but we did what Freddie asked us to do," said Flyers Hall of Fame defenseman Joe Watson. "We didn't do it a lot but that's one I remember that he liked to roll out once in a while, especially during camp."

During a Shero-run training camp, and continuing through the season, it was common for Flyers players to be sent off to a corner of the rink to do pushups if they messed up during a practice drill or were caught being inattentive. The player would go off to do the task and Shero or assistant coach Mike Nykoluk would resume the drill with the players. Longtime Flyers beat writer Wayne Fish recalls an occasion when Shero suddenly blew the whistle after re-starting a drill and called over to Andre "Moose" Dupont without ever looking his way. Dupont had been dispatched to do 20 pushups. The player complied, sort of, Dupont did the exercise from his knees rather than from a proper push-up position.

"Dupont! When you're done screwing around, do 40 pushups the right way," Shero said, doubling his initial demand.

The coach had his back to Dupont the whole time. Fish wondered how Shero knew the player wasn't truly complying. What gave him away? Shero later explained that there were other players glancing in their teammate's direction and grinning. The coach realized right away what was going on in the far side corner.

Until fairly recent times, training camps were a time for players to shed whatever pounds -- not the muscular type of added weight -- that they'd put on during the summer. They also needed to recover their cardiovascular conditioning to get into shape for the season. With some exceptions, working out was rarely high on offseason priority lists. When players had free time in the offseason, the preferred activities were often comprised of some combination of fishing, hunting, beer drinking and/or golfing.

So much has changed with NHL training camps over the years. Below is the text of Flyers general manager Bud Poile's pre-camp letter to players back in 1968. pic.twitter.com/qiC4m7cGCE

— Bill Meltzer (@billmeltzer) September 8, 2022

Bob Clarke, by the standards of his playing era, was one of the first NHL players who took pride in physical fitness and gym training. After the Flyers won their first Stanley Cup in 1974, team captain Clarke instructed his teammates to report to camp in the best shape of their lives. Most of the guys complied, which in those days meant showing up at camp either at their playing weight or at least no more than three or four pounds over it.

From the mid-1980s to late 1990s, the Flyers' training complex was at the Coliseum in Voorhees. The facilities were a decided upgrade from their former digs. The expectations bar from a training standpoint was raised considerably when Pat Croce became the team's full-time strength and conditioning coach, especially during the era when Mike Keenan was the Flyers' head coach. Both Keenan and assistant coach E.J. McGuire were themselves fitness enthusiasts, so they recognized the importance of incorporating a more systematic off-ice training regimen into playing preparations. Croce, for all intents and purposes, was every bit as important to the team as the on-ice coaches.

The Flyers' on-ice success during this era compelled other teams to implement more modernized training facilties and programs. The evolution wasn't uniform. A decade later, there were still a couple straggler teams that had little more onsite at their facilities than a few stationary bikes. Keenan recalled that he was dismayed when he became the Boston Bruins head coach in 2000 and discovered their on-hand training equipment was relatively sparse and outdated. He demanded an immediate overhaul. Eventually, every NHL team eventually got fully on board when they realized there was a competitive advantage at stake. Nowadays, even NHL team programs on the cutting edge of training techniques and sports science have a more modest advantage compared to leaguewide norms.

The Flyers relocated their facilities again in 1999 from the Coliseum to the Voorhees complex now known as the Flyers Trainining Center (formerly the Skate Zone). In 2017, the Flyers completed the final phase of a behind-the-scenes overhaul of its training complex home base. First came an all-new locker room for the Flyers players. Then came an expansion of the gym facilities. Finally, there came the rollout of the state-of-the-art Performance Center. All of the bases are covered whether it is skill development resources, (including a room devoted strictly to practice shooting the pick), equipment designed for strength, agility or endurance training, a dedicated recovery room, private meeting rooms, video access and an ever-increasing presence of sports science data, player-specific coaching and feedback.

Training camp and the business side of hockey

:

Old-school training camps differed from their new millennium descendants for practical reasons, too.

There was once a time -- mostly before the 1970s -- when a large percentage of NHL players held down non-hockey jobs in the offseason to supplement their incomes. They didn't make enough money from hockey for it to be their only profession. Thus, whether it was working in a factory or a family farm or some other means to supplement their incomes, many old-time players simply couldn't afford to focus on an off-season training schedule -- a rest period to recuperate, following by a gradual ramp up from light to intensive skating as well as off-ice workouts -- to get ready for the next season.

"I made $3,000 my first year of pro hockey," recalled Watson, referring to the 1963-64 season with the Boston Bruins' minor league affiliate in Minneapolis. Even after becoming a full-time NHL player for Boston in 1966-67, he held a summer job for the public works department in his native Smithers, British Columbia. It was not until the early 1970s that Watson made enough from playing hockey that he could make it his year-round job. Even then, he was hardly getting rich off the game.

Until off-season free agency became a significant factor in player movement across the National Hockey League, it was common for players to report to training camp without a contract for the upcoming season. Many players represented themselves in negotiations, rather than hiring an agent (even then, in the early years, there were only two notable NHL agents to choose from). Contracts were done in assembly-line fashion. At the start of camp, the GM would summon the players to his office or to a hotel room where he headquartered during camp.

Flyers Alumni player and broadcaster Bill Clement recalled a story where he was summoned to work out a new contract with Hockey Hall of Fame general manager Keith Allen at his tiny office at the Class of 1923 rink the day before camp opened. Allen cut to the chase right away.

"How much do you want?" Allen said, holding a pencil and a note pad.

"$22,500 for the NHL, $16,500 for [AHL affilate] Richmond," Clement said.

Allen had expected Clement to either say "Whatever you think is fair" or to ask for a relatively negligible raise. He stared daggers at Clement, and then tossed his pencil and notepad airborne in disgust.

"Who do you think you are? We have some players here who think their worth the moon and the stars. You know what? I'm not even going to negotiate. I'll send you to arbitration. Get out!"

Crestfallen, Clement slunk out of the general manager's office.

"I didn't even know what arbitration was," Clement recalled.

The next day, Allen told Clement to see him at a downtown hotel room, where he had a desk set up by the window.

"Contract is on the table," Allen said. "That's all I'm going to do. Take it or leave it."

Clement walked over to the desk. There was a pen laying atop the contract paperwork. Glancing at the document, Clement saw that it called for a $16,500 salary at the NHL level and $12,500 in the AHL.

The player took the pen and signed the contract.

By the 1990s, virtually every NHL player had an agent. Even then, however, it was not unheard of for some players (not including one on professional tryout (PTO) arrangements) to arrive at training camp and join the team on the ice without a contract in hand. The last notable Flyers player to do was left winger John LeClair in 1995. A restricted free agent in the summer coming off a breakout 1994-95 season after being acquired from Montreal, LeClair reported to camp without a contract. The multi-year deal was signed on Sept. 11, 1995. Two years later, with term remaining on the contract, LeClair was a brief holdout early in camp. After he reported, the contract was renegotiated and replaced with a new four-year contract.