Nine Days that Shaped the 1990s Flyers

In advance of the 1990s Throwback Thursday game against the original Winnipeg Jets (whoops, Arizona Coyotes), here's a look back at nine memorable moments that helped define the decade for the Philadelphia Flyers

1. May 25, 1997: Flyers Win Eastern Conference Championship

The zenith of the 1990s for the Flyers came on the afternoon of May 25, 1997: Game 5 of the 1997 Eastern Conference Final against the New York Rangers.

The Philadelphia Flyers tore through the 1997 Eastern Conference playoffs. The team needed just five games apiece to dispatch the Pittsburgh Penguins, Buffalo Sabres and star-laden but aging New York Rangers to win the Prince of Wales Trophy and advance to the seventh Stanley Cup Final berth in franchise history.

In Game 5 of the Eastern Conference Final against the Rangers, the scene shifted back to Philadelphia's brand-new Wells Fargo Center (then called the CoreStates Center) after the Flyers prevailed in hard-fought matches in Games Three and Four at Madison Square Garden.

Flyers captain Eric Lindros brought the home crowd to its feet as he opened the scoring with an early power play goal. The Philly fans were briefly silenced by back-to-back Rangers power play goals (Alexander Karpovtsev and Esa Tikkanen) on both sides of a 5-on-3 New York power play. However, the atmosphere was electric again as John LeClair knotted the game on a power play goal and Rod Brind'Amour tallied at even strength to put the Flyers ahead before the first intermission.

Philadelphia dominated a scoreless second period, holding the Rangers to just two shots on goal but the Flyers could not extend their lead against Mike Richter (who finished with 25 saves). Finally, at 6:43 of the third period, Brind'Amour notched his second tally of the game as he provided some insurance with a 4-2 lead.

That was all Ron Hextall needed. He turned away all eight shots he saw in the final period. Ten years after a rookie Hextall brought the Flyers within a narrow Game 7 defeat of winning the Stanley Cup, the Flyers were headed back to the Final.

The 1997 Stanley Cup Final against the Detroit Red Wings put a damper on the otherwise highly successful Terry Murray era. The Flyers lost in four straight games. Nonetheless, "Murph" still holds the second highest postseason winning percent (.609) of any coach in Flyers' franchise history; higher, in fact, than legendary two-time Stanley Cup winning coach Fred Shero (.578), fellow Hockey Hall of Fame coach Pat Quinn (.564) or "Iron" Mike Keenan (.561).

2. June 30, 1992: Arbitrator Awards Lindros' Rights to the Flyers

Drafted by the Quebec Nordiques with the first overall pick of the 1991 NHL Draft, Lindros declined to play for the team. A fierce bidding war ensued, with numerous NHL teams offering massive returns to the Nordiques for the rights to the highly touted teenagers. For the next year, the Nordiques declined all offers, as the prices escalated higher and higher.

Finally, in one of the biggest blockbuster deals in NHL history, the Nordiques verbally agreed to a June 20, 1992 trade with the Flyers that sent Lindros' rights to Philadelphia in exchange for NHL roster center Mike Ricci, goaltender Ron Hextall, defensemen Steve Duchesne and Kerry Huffman, Swedish prospect Peter Forsberg (the Flyers' 1991 first-round pick), $15 million (USD) in cash, the earlier of the Flyers' two first-round picks in the 1992 NHL Draft and the Flyers first-round picks in the 1993 (Jocelyn Thibault) and 1994 drafts (Nolan Baumgartner).

After verbally agreeing and shaking hands with the Flyers on the deal, the Nordiques turned around and decided instead to trade Lindros' rights to the Rangers. Although not revealed publically, the New York trade offer included forward Alexei Kovalev, goaltender John Vanbiesbrouck and future star forwards Doug Weight and Tony Amonte along with similar cash compensation and draft pick assets.

With the disputed trade held up by the NHL, the Flyers selected Ryan Sittler with the seventh overall pick of the 1992 NHL Draft. On June 30, 1992, following emotionally charged arbitration hearings in Toronto, arbitrator Larry Bertuzzi ruled that the Flyers had made an enforceable trade and the Rangers deal was nullified. To complete the trade with Philadelphia, the Nordiques accepted enforcer prospect Chris Simon (whom the Flyers had drafted in the second round of the 1990 Draft) in lieu of the pick already used by the Flyers on Sittler.

The Lindros trade to Philadelphia would go on to become one of the most debated deals in NHL annals. The reality: both sides benefited. Forsberg went on to have a Hall of Fame career of his own and the deal was a boon to the Nordiques (later Colorado Avalanche) in assembling an eventual two-time Stanley Cup champion and perennial contender. In the meantime, Lindros's talent came as advertised, and he became a franchise player on Flyers teams that were built into perennial contenders in their own right.

3. April 11, 1996: Final Regular Season Game at the Spectrum

The fabled Spectrum was the Flyers home rink from the inaugural 1967-68 season through the 1995-96 campaign. During those years, the Flyers enjoyed a 699-296-143 record on home ice in the regular season (.677 points percentage). In the Stanley Cup Playoffs, the Spectrum hosted 131 Flyers home games (third most in the NHL), in which the Flyers held a record of 79-52 (.609 winning percentage).

Among the most notable hockey events held in the multi-purpose building during this time period, the Flyers won the 1974 Stanley Cup on home ice, defeated CSKA (the Red Army team) in 1976, and hosted the 1976 and 1992 NHL All-Star Games. Finally, on April 11, 1996, the Flyers took on the Montreal Canadiens in the final regular season NHL game held in the arena.

On that evening, the Flyers defeated the Habs, 3-2, to clinch the Atlantic Division championship.

First period goals by Shjon Podein (shorthanded) and John Druce built a 2-0 lead. After the Habs drew back within 2-1, John LeClair's 51st goal of the season, set up by Hockey Hall of Famers Dale Hawerchuk and Eric Lindros, restored a two-goal lead for Philadelphia. Montreal once again cut their deficit to a single goal before the second intermission. However, the Flyers slammed the door in the third period, holding the Habs to just four shots on goal. Ron Hextall (17 saves on 19 shots) earned the win in goal.

All fans in attendance received a commemorative "Thanks for the Memories" poster, featuring a collage of key moments and Flyers players from the Spectrum era. After the game, a special "closing ceremony" was held to honor the teams of the past and present.

The biggest highlight of the ceremony: One by one, each then-current player on the Flyers roster skated one lap apiece around the rink paired alongside an alum player: for example, Sean Antoski with with Dave "the Hammer" Schultz, Podein with Gary Dornhoefer, Chris Therien with Behn Wilson, Petr Svoboda with Ed van Impe, Trent Klatt and Bob "the Hound" Kelly, Rod Brind'Amour and Tim Kerr, Bill Barber and John LeClair, goalies Hextall and Garth Snow with Bernie Parent, Mikael Renberg and Reggie Leach and Lindros with Bob Clarke. In honor of his late father, Barry, Danny Ashbee skated a lap with Russ Romaniuk.

4. Oct. 5, 1996: First Regular Season Opener at the Center

The inaugural event at the CoreStates Center (now Wells Fargo Center) was the 1996 World Cup of Hockey. The arena hosted a preliminary round game between Team USA and Team Canada. a semifinal single-elimination match between Team Canada and Team Sweden and Game 1 of the best-of-three championship series between Team USA and Team Canada.

A host of Flyers played in the World Cup of Hockey, including John LeClair and Joel Otto for eventual champion Team USA and the trio of Rod Brind'Amour, Eric Desjardins and Eric Lindros for Team Canada. Renberg was initially slated to play for Team Sweden but was forced to withdraw while recuperating from surgery to repair a 100 percent lower abdominal muscle tear. Veteran Flyers defenseman Petr Svoboda competed for Team Czech Republic and incoming Flyers rookie defenseman Janne Niinimaa suited up for Team Finland.

All three World Cup games hosted by the Flyers' new home arena were thrillers. Shortly after the tournament, NHL training camps commenced. Finally, on Oct. 5, 1996, the Flyers played the defending Eastern Conference champion Florida Panthers in the first-ever regular season game in the new building.

The game itself did not go as hoped. Trailing 1-0 early in the first period, debuting 18-year-old Flyers rookie winger Dainius Zubrus scored to knot the score at one goal apiece. Shjon Podein and Chris Therien earned the assists. Thereafter, John Vanbiesbrouck (31 saves on 32 shots) and the Panthers neutral-zone trap and clutch-and-grab style frustrated the Flyers in similar fashion to the Eastern Conference Semifinal series five months earlier.

In the second period, former Flyers power forward Scott Mellanby put the Panthers ahead, 2-1. That's how the score remained until Johan Garpenlöv tacked on an empty-net goal in the final eight seconds of regulation. The Flyers lost, 3-1. Ron Hextall finished with 17 saves on 19 shots.

Flyers captain Lindros was unavailable to play in the opener. He suffered a groin pull in the World Cup tournament (along with elbow bursitis). The groin issue, which was aggravated twice while the player attempted to ramp up his rehab skating program, would keep Lindros out of the first 23 games of the 1996-97 season. When he finally returned, Lindros did so with a vengeance. He'd rack up 79 points (32 goals, 47 assists) in just 52 games played during the regular season.

5. January 19, 1992 : NHL All-Star Game

The National Hockey League All-Star Game returned to the Spectrum in 1992 as part of the leaguewide celebration of the 25th anniversary season since the 1967 expansion. The festivities included a game between the Flyers Alumni Team and a team of NHL Alumni. Bob Clarke, at the time the general manager of the Minnesota North Stars, received a standing ovation from the Spectrum when introduced during the All-Star events as the honorary captain of the Wales Conference team.

In the All-Star Game the Flyers were represented by Rod Brind'Amour, who received the largest ovation during the Skills Competition the previous evening. Brind'Amour scored a goal during the climactic breakaway relay. In the All-Star Game itself, the Wales Conference prevailed by a 10-6 score.

Flyers All-Star Moments: 1992 All-Star Game at the Spectrum

— Flyers Alumni (@FlyersAlumni) February 4, 2022

Rod Brind'Amour represented the Flyers in the ASG. Bob Clarke served as honorary captain of the Wales Conference All-Stars. pic.twitter.com/3renI3oDUA

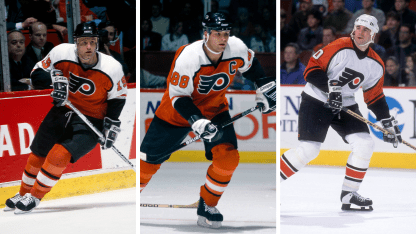

6. February 6, 1997: The Legion of Doom's Most Dominant Night

The original Legion of Doom trio of center Eric Lindros, left wing John LeClair (and right wing Mikael Renberg ran roughshod over the NHL for the three seasons they were together: 1994-95, 1995-96 and 1996-97. In the final season, Renberg struggled for months to recover his formerly explosive skating after suffering a severe sports hernia that kept him out most of the second half of the prior season. However, Lindros (once healthy after missing the first 23 games of the season) and LeClair were as dominant as ever. In the second half of the 1996-97 season, Renberg finally seemed to be returning to form, too.

During their final season together as a regular three-man unit, the Legion of Doom had the best collective single-game performance of their entire run. On the night of Feb. 6, 1997, the host Flyers shellacked the Montreal Canadiens by a 9-5 score. The Legion of Doom set a still-standing Flyers team record with a combined 16 points: six by ex-Hab LeClair (4g, 2a), and five apiece for Lindros (1g, 4a) and Renberg (1g, 4a). Later that same month, on the road in Ottawa on Feb. 26, the L.O.D. combined for 15 points: a career-high seven for Lindros (1g, 6a), four for LeClair (hat trick, one assist) and four points for Renberg (2g, 2a).

7. Feb. 9, 1995: Blockbuster Trade with Montreal

The early 1990s were a bleak period in Flyers history. Following a run to Game 6 of the 1989 Wales Conference Final, the team would miss the playoffs in each of the next five seasons (1989-90 to 1993-94). There were a few bright spots along the way, such as the arrival of Eric Lindros, the emergence of Rod Brind'Amour after being acquired in a 1991 offseason trade with the St. Louis Blues, Mark Recchi recording back-to-back 100-plus point seasons (including a still-standing franchise record 123 points in 1992-93) after coming over from the Pittsburgh Penguins in a blockbuster trade at the 1991-92 trade deadline, and Mikael Renberg setting a still-standing Flyers rookie scoring record in 1993-94 (38 goals, 44 assists, 82 points) on the way to being a Calder Trophy finalist for NHL Rookie of the Year.

However, it would not be until the lockout-shortened 1994-95 season that the Flyers' fortunes would turn for the better. Even the 1994-95 season itself got off to a rough start. The Flyers were 3-7-1 after 11 games. On February 9, 1995, the Flyers made a blockbuster trade with Montreal. Philadelphia parted with star forward Recchi in order to acquire defenseman Eric Desjardins, John LeClair (then a third-line center in Montreal) and winger Gilbert Dionne from the Montreal Canadiens. The Flyers also sent a 1995 third-round pick (Martin Hohenberger) to the Habs in the deal.

In Philadelphia, the deal was initially skewered by the fans and segments of the media. On the day the trade was made, WIP Radio was flooded with calls from Flyers fans who were irate at the return the team was getting for Recchi. Later that night, the Flyers were shut out at the Spectrum by Florida, 3-0, for Philly's second straight shutout loss. Three nights earlier, the lowly Ottawa Senators (the NHL's worst team at the time) had similarly defeated the Flyers by a 3-0 score. From there, however, things turned around rapidly in the Flyers' favor.

The big trade proved to be the capstone of a quick and dramatic turnaround marked by reshaping of the entire Flyers' blueline and the surprise emergence of LeClair as an NHL superstar after being a role player in Montreal. On the whole, the lockout-shortened 1994-95 season ended up being a major positive shift in the Flyers' on-ice fortunes. That was the year where Philly, after five years of missing the playoffs, re-emerged as a Stanley Cup contender.

Training camp started as scheduled that year prior to the lockout. It is easy nowadays to forget that the team in Sept. 1994 was still considered too suspect on defense and in goal to be a playoff caliber club. New coach Terry Murray and newly rehired GM Bob Clarke had their work cut out for them.

The previous season, the starting defense primarily consisted of Garry Galley, Dmitri Yushkevich, Jeff Finley, rookies Jason Bowen and Stewart Malgunas, tough guy Ryan McGill and various in-season acquisitions such as Rob Zettler and Rob Ramage (a former four-time NHL All-Star and two-time Cup winner who, at age 35 was at the end of the line in his NHL career).

In goal, the Flyers had the duo of Tommy Söderström and Dominic Roussel. Both had been touted for a time as the potential long-term "goalie of the future" -- Söderström had particularly impressed as a rookie in 1992-93 with 5 shutouts in 44 games -- but their ongoing inconsistency was a major concern.

Against that backdrop, Clarke set out to remake the team defensively, while the defensive-minded Murray preached discipline and defensive responsibility:

As it soon turned out, coach Murray's decision to make LeClair a full-time winger and play him with Eric Lindros and Mikael Renberg ended up working out better than anyone could have imagined. With the birth of the Legion of Doom line, the Flyers never missed Recchi's production even despite his back-to-back 100-plus point seasons prior to the trade.

Just as important, the acquisition of Desjardins helped stabilize the blueline. He would immediately become the Flyers' best defenseman for most of the next decade; a seven-time winner of the Barry Ashbee Trophy (including in 1994-95). His pairing with Haller was highly effective in both 1995 and the 1995-96 campaign because they were two of the most mobile defensemen in the NHL. Later, in 1996-97, Desjardins would begin a long-running defense pairing partnership with Therien. Previously, Therien's primary partners were Dmitri Yushkevich (1994-95 season) and Kjell Samuelsson (1995-96).

Clarke still wasn't done remaking the blueline after acquiring Desjardins. On Feb. 16, 1995 the Flyers and Blackhawks swapped struggling young defensemen, with Karl Dykhuis (a 1990 first-round pick who had been highly touted entering the pros) coming to Philadelphia and Bob Wilkie going to Chicago. Dykhuis immediately stepped into the NHL lineup.

Just before the trade deadline, Clarke sent Galley to Buffalo in exchange for the mobile and ultra-steady (but injury prone) Petr Svoboda. Svoboda helped smooth some of young partner Dykhuis' rough edges. Thus, by the start of the 1995 playoffs, the Flyers had changed over their starting goaltending and five of their six starting defense slots - Zettler remained on as the seventh defenseman - from the end of the previous season. But it wasn't just change for change's sake. Virtually every move ended up making the Flyers a better team.

Clarke's work from the summer of 1994 to the end of the 1995 season was one of the best years seen from an NHL general manager in the last quarter century. Legendary Flyers general manager Keith "the Thief" Allen couldn't have done it any better that year. Clarke also accomplished the turnaround without spending a significant amount of extra money on salaries that season.

Meanwhile, Murray made the Flyers much more accountable defensively as a team. Some of the forwards may not have always liked it, but they saw the results in the standings and with two trips to the Eastern Conference Final (one of which extended to the 1997 Stanley Cup Final) in the next three seasons.

In the big picture, it wasn't the trade with Montreal alone that brought about the Flyers' transformation from five years of missing the playoffs to perennial contender. Nonetheless, the single biggest aspect of the team's revival came from bringing LeClair and Desjardins aboard to join with Lindros, Renberg, and Brind'Amour.

8. November 13, 1991 and Dec. 5, 1991: The Dineens Form Flyers Coach and Player Duo

As noted above, the early 1990s was a transitional period in Flyers history. In 1991-92, the team was in the midst of a five-season stretch that marked the dismantling of the Mike Keenan-era Stanley Cup finalist teams and the trades that brought Rod Brind'Amour, Mark Recchi and eventually Eric Lindros to Philadelphia. These were not happy times in Flyers history. But there were some rays of hope.

The acquisition of feisty 28-year-old right winger Kevin Dineen from the Hartford Whalers in November of 1991 helped restore some of the hustle, grit and never-say-die attitude that had always been central to the team's identity but which had gone AWOL. A few weeks after the player came to Philadelphia, he was joined by his 59-year-old father, the late Bill Dineen, who accepted the Flyers' head coaching position after the club got off to an 8-14-2 start.

Despite the continued upheaval of the roster, the elder Dineen got his young, outgunned team to overachieve, posting a winning record over the remaining 56 games of the season. At a time when the Flyers were in need of something to lift their spirits, Dineen was the right man for the job.

"Foxy was pretty unique among the coaches I played for in my career," said Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman Mark Howe, who also played for the coach in the WHA. "With most coaches, the players sit around together in the locker room or a bar after a loss and gripe about this or that thing about the coach. With Bill, when you lost, the players felt like they let him down. He was always in his players' corner. There was no ego, no politics with Foxy. He cared about every one of his players, on the ice and as people. He was a good coach, and an even better man."

Meanwhile, the younger Dineen brought some much-needed goal scoring to a lineup that only had three players score 20 or more goals that season. In 64 games that season for the Flyers, Dineen ranked second on the club with 26 goals (including five on the power play and three shorthanders) and 56 points.

"We lost a quality hockey player in Murray Craven when the Flyers traded him to get Kevin from Hartford, but I think the team really needed what Kevin brought with him," Howe recalled in 2014. "We were in a bad situation where there were some players who wanted out and some who were content with losing or making excuses. It wasn't fun. Dino was a guy who loved to come to the rink and, win or lose, played the game the right way."

By the time Bill Dineen made his NHL coaching debut on December 5, 1991, 6-3 loss at the Spectrum to the Washington Capitals, he had been in the hockey business for nearly 40 years as a player, coach and scout.

As a player, Dineen broke into the NHL with the Detroit Red Wings in 1953-54, playing in 70 games as a rookie, scoring 17 goals and eight assists for 25 points. Nicknamed "Columbo" or "the Fox" (alternatively, "Foxy") for the way he slyly got outsiders to underestimate him, the well-liked Dineen was a hard-working sparkplug on the ice and a fun-loving guy who snuck in past curfew a time or two off the ice. After four-and-a-half years with Detroit, including a pair of Stanley Cup championships, Dineen was traded to the Chicago Blackhawks in the middle of the 1957-58 season.

Dineen finished the season with the Hawks, but struggled for points. After the campaign, he was informed that he no longer fit into Chicago's plans. At the age of 27, Dineen decided to continue his career, even if it meant playing in the minor leagues. That's where he remained for the rest of his active career, finally retiring at age 38 after spending part of the 1970-71 season and all of the 1971-72 campaign as a player-coach of the Denver Spurs (WHA).

During his playing days, Dineen was particularly close with the legendary Gordie Howe. Like the late Mr. Hockey and his late wife Colleen, Bill and Pat Dineen never pressured their children to play the sport. Bill simply passed along the joy of the game to sons Shawn (born 1958), Peter (1960), Gordie (1962), Kevin (1963) and Jerry (1966). Every one of the Dineen boys played pro hockey with Peter, Gordie and Kevin making it to the NHL.

Kevin Dineen was born in Quebec City on October 23, 1963. At the time, his dad was playing in the AHL for the Quebec Aces. But like many hockey families, the Dineens moved around as Bill's career dictated. Kevin spent the majority of his early childhood in Seattle, while his father was with the Seattle Totems, but later lived in Denver, Houston and other locales.

In 1972, Bill Dineen accepted the head coaching job with the WHA's Houston Aeros. The next year, he was reunited with old friend Gordie Howe, who came out of retirement to play alongside sons Mark and Marty. The club went on to win consecutive WHA championships and was runner-up the next year. Dineen later moved on to the New England (later Hartford) Whalers, where he once again coached the Howes.

During these years, the Dineen boys were frequently around the teams' locker rooms. In the words of Bill Dineen, Gordie Howe was like a favored uncle to all of his sons but "took a special shine" to Kevin in particular.

"Kevin was the one with the most mischief in him among my sons, and a charmer as well," the elder Dineen said in Stan Fischler's book, The Greatest Players and Moments of the Philadelphia Flyers. "Gordie likes Kevin because no matter how rough he handled him - picking him up by the ears and all that - Kevin would always come right back at him."

Kevin Dineen played both forward and defense early in his youth hockey career before settling in at wing. In addition to his goal scoring prowess, he had a Tasmanian devil quality to his game. Kevin absolutely hated to lose and wouldn't back down from even the toughest of foes.

"Dino wasn't just a goal-scorer for his teams. He was a tone-setter," said Dave Tippett in 2014. TIppett, a longtime NHL head coach, had played against Kevin Dineen in the WCHA and with him in the NHL in both Hartford and Philadelphia.

Coincidentally, two of the Dineen boys were chosen in the NHL draft with picks belonging to the Flyers. The Flyers drafted Peter, a defenseman, in the ninth round of the 1980 draft. Although he kicked around the Philadelphia farm teams for several years, he never suited up for the Flyers. He eventually had brief stints with the Los Angeles Kings and Detroit Red Wings.

Kevin, meanwhile, was selected by Hartford in the 3rd round (56th overall) in the 1982 draft with a pick originally sent from the Flyers to the Whalers in the multi-player and draft-pick swap in July 1981 that sent Rick MacLeish to Hartford. In that deal, the Flyers received Ray Allison, the1982 first-round pick used to select Ron Sutter and the third-round pick used for veteran Czech defenseman Miroslav "Cookie" Dvorak.

Kevin enjoyed a solid two-year college career at the University of Denver, where he majored in business management. During his freshman year, he scored 10 goals and 20 points in 26 games. The next season, he posted 16 goals and 29 points in 36 games while setting a team record for penalty minutes in a season with 105 penalty minutes.

In 1983-84, Kevin was invited to try out for Team Canada during the pre-Olympic tour. Playing both forward and defense, he won a spot on the 1984 Olympic roster in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia. With countries like the USSR and Czechoslovakia using their top professional players, the amateur players on Team Canada didn't stand much of a chance at a medal.

The Canadian squad won four of five games in the preliminary round (the one blemish was a 4-0 loss to Czechoslovakia) but were overmatched in the medal round, getting shut out 4-0 by the gold-medalist Soviets, 2-0 by Sweden and 4-0 again by the Czechoslovaks.

Kevin turned pro after his year with the Canadian national team. Meanwhile, Bill Dineen had gotten back into coaching after a four-year absence. He took on the head coaching job for the AHL's Adirondack Red Wings in 1983-84, where he remained for six seasons.

Under Bill Dineen's patient tutelage, Adirondack won two Calder Cup championships before he stepped down in 1989 in favor of the much younger Barry Melrose. During his tenure, the Fox also gained the nickname Lt. Columbo, in honor of the television detective who feigned ineptitude but was supremely skilled in his chosen profession.

The gravelly voiced Dineen patriarch often acted like he had wandered into the wrong building and found himself behind the bench by accident. In reality, the man knew how to win hockey games and get the most out of his players. As the late Jay Greenberg wrote in Full Spectrum, "Dineen asked the players how they were and really listened to the answers."

While his father was winning championships as a coach in the American League, Kevin Dineen was steadily making a name for himself in the NHL. As a rookie in 1984-85, he scored a very respectable 25 goals and 41 points in 57 games, to go along with 120 penalty minutes.

Over the next four seasons, he never scored fewer than 25 goals, cracking the 40-goal barrier twice (with a high of 45 in 1988-89). In 1987, Dineen was part of the victorious Team Canada squad that defeated the Soviet Union in what is considered the finest Canada Cup series played in the tournament's history.

The Whalers were a perpetual also-ran in the 1980s and 1990s, but that was hardly Kevin Dineen's fault. Montreal Canadiens' coach Jean Perron called the 5-foot-11, 190-pound right winger "one of the most inspirational players I have ever known."

During the late 1980s, virtually every NHL team asked Hartford whether Dineen was available in trade. The answer was always a flat no. That changed after the 1990-91 season.

In 1987, Dineen was diagnosed with Crohn's Disease, a painful and incurable digestive disorder. In December of 1990, a severe flare up of the condition caused Dineen to miss several games and ultimately resulted in him being hospitalized on January 2, 1991. Over an eight-day span, Dineen lost 10 pounds.

Dineen returned to the Whalers lineup on January 23, 1991. Although he refused to use his condition as an excuse for sub par play, the player was still not fully recuperated. He finished the season with just 17 goals, 47 points and 104 penalty minutes in 62 games.

Hartford management publicly expressed support for Dineen but was privately worried whether the soon-to-be 28-year-old would be able to recover his previous form. When Dineen got off to a slow start in the 1991-92 season (four goals, six points in 16 games), the club listened to several trade offers from other clubs.

Flyers general manager Russ Farwell was looking to shake up the roster. The team had missed the playoffs the previous two seasons and stumbled out of the gates in October and November of the current season. On November 13, 1991, Philadelphia and Hartford struck a deal. The Flyers sent veteran Craven and a 1992 fourth-round draft choice (Kevin Smyth) to the Whalers in exchange for Dineen.

The next night, Dineen was placed on right wing on the line centered by first-year Flyer Rod Brind'Amour. Dineen scored his first goal as a Flyer in the closing seconds of regulation to seal a 3-1 win over the Edmonton Oilers. Two nights later, the Flyers downed Montreal, 3-1.

Unfortunately, the wins proved to be the final ones of Paul Holmgren's three-plus season tenure as head coach. The club went on to lose six of its next seven games with one tie. Farwell sought the counsel of Bill Dineen, who had been hired by the club as an amateur scout. The GM asked the elder Dineen, who had been scouting a Western Hockey League league game, to fly out to New York to see the Flyers play the Rangers on December 2. After the 4-2 loss, Farwell and Dineen sat together in the lobby of the Paramount Hotel.

As recounted in Full Spectrum, Farwell told Dineen he was seriously contemplating a coaching change. He asked Dineen to suggest some candidates, and was told that Flyers assistant coaches Ken Hitchcock and Craig Hartsburg had promising futures in Dineen's estimation.

The GM replied that he didn't think either assistant was ready yet. Dineen then suggested Hershey Bears coach Mike Eaves or Adirondack's Barry Melrose. Again, Farwell said no. Several minutes later, he asked Dineen if he'd consider coaching the Flyers.

Dineen's incredulous response, per Full Spectrum: "Was there something in your drink at the restaurant?"

Dineen thought at first that Farwell was joking, which prompted Dineen to jest in reply. Soon, though, he realized that Farwell was serious. He wanted Dineen to take over as head coach.

"I dunno, Russ. I gotta think about it," Dineen said.

The general manager asked him to sleep on it. Dineen flew home the next morning and kept quiet, not even telling his wife about the conversation. After receiving a phone call from Farwell the next evening, confirming the coaching offer and a proposed financial compensation adjustment from a scout's salary to that of a head coach, Dineen headed down to the basement of his house. "Foxy" retrieved his skates. He asked his wife, Pat, if she thought the skates were too rusty to be used or could still be rescued.

The hockey wife and mother immediately knew something was up.

"Don't tell me," she said to her husband.

"Yup," he replied.

The following day, the Flyers announced the coaching change. The last player to find out the news was Kevin Dineen. He learned when he arrived at the rink and Kjell Samuelsson told him that "Billy is going to have a meeting first."

"Billy who?" Kevin asked.

"Your father," Samuelsson responded. "You haven't heard?"

Bill Dineen was always careful to avoid showing any sort of favoritism toward his son. If anything, Kevin was the one player on the Flyers' roster from whom he distanced himself. When the head coach held one-on-one meetings with his players - something he did frequently in order to sound out their views on the club and their own performance - he intentionally avoided Kevin. Around the locker room, he always referred to his son as "Dineen."

The elder Dineen viewed these actions as a means of protecting his son from feeling awkward on the team. But he needn't have worried. Kevin had quickly become one of the most respected players in the locker room and a fan favorite at the Spectrum.

Apart from linemate Brind'Amour, who was the Flyers' lone representative at the 1992 NHL All-Star Game at the Spectrum, the play of Dineen was one of the few bright spots on a Flyers club that staggered through the first half of the season.

In the second half of the season, Bill Dineen put former Montreal Canadiens left winger Mark Pederson on the left wing of Brind'Amour's line with Dineen. The trio clicked.

Pederson, whose NHL career was largely a disappointment after being a highly touted prospect in junior hockey, scored 12 goals and 35 points over the final 44 games of the season, while Dineen finished a strong rebound year with 30 goals and 62 points in 78 games and Brind'Amour scored 33 goals and 77 points.

In the spring the Flyers made a major trade, sending disgruntled captain Rick Tocchet, defenseman Kjell Samuelsson and goaltender Ken Wregget to the Pittsburgh Penguins in exchange for burgeoning star right wing Mark Recchi, defenseman Brian Benning and a 1993 first round draft pick.

After getting buried early in the season, Flyers didn't have much to play for except pride. But Bill Dineen's positive messages got the players to believe in themselves.

From January 28 until the end of the season, the Flyers went 19-14-1. Many of the club's best performances came against the top clubs in the league, including victories over first-place clubs Montreal, Detroit and the New York Rangers. The Flyers' one tie was an exciting 3-3 deadlock with the eventual Stanley Cup champion Penguins in a game where Kevin Dineen and Rod Brind'Amour spurred comebacks from deficits of 2-1 and 3-2.

In total, Bill Dineen coaxed his club to a winning record over the 56 games he coached during the 1991-92 season. He had to deal with frequent injuries, major roster changes, lack of scoring depth and frequent defensive problems, and yet a cohesive team emerged.

"If you can't play for someone like Bill Dineen, I don't know if there's any coach you can play for. As for Kevin, I only played one year together with him on the Flyers before I left and signed with Detroit, but he was a tremendous teammate and a quality person," said Mark Howe in 2014.

In his Columbo-like way, Bill Dineen slyly breathed life and confidence back into a struggling team that had been given up for dead. While it wouldn't be until 1995 that the Flyers would re-emerge as a Stanley Cup contender, the coach got his teams to play to the best of their ability.

In his second and final year as coach, the still-undermanned Dineen-led Flyers club might have snuck into the playoffs if rookie phenom Eric Lindros had not missed 23 games due to injury. As it was, the club only missed out by four points. In addition to Lindros' 41 goals and 75 points, Recchi set a club single-season record with 123 points. Meanwhile on the second line, Brind'Amour produced 37 goals and 86 points. Pugnacious as ever, Kevin Dineen tallied 35 goals, 63 points and a career-high 201 penalty minutes.

9. Aug. 4, 1997: Flyers Sign Gratton to Offer Sheet

On August 4, 1997, the Flyers signed Tampa Bay Lightning restricted free agent center Chris Gratton to an offer sheet. The deal was a five-year contract, paying a total of $16.5 million, which included a $9 million signing bonus payable in seven days.

Flyers' general manager Bob Clarke had coveted Gratton ever since the 1993 Draft, in which Tampa selected Gratton with the third overall pick. The big center came along slowly in his first three NHL seasons but appeared to turn a corner in 1996-97, scoring 30 goals, 62 points and racking up 201 penalty minutes.

The Flyers were not particularly in need of another center. They already had Eric Lindros and Rod Brind'Amour to anchor the scoring lines, with Joel Otto on the third line. They also had promising young Vaclav Prospal, who had been a center with the Phantoms and was called up to the big club in the latter part of the 1996-97 season (posting 15 points in 18 games and 4 points in 5 playoff games before suffering a season-ending broken wrist).

Nevertheless, the Flyers went ahead in their pursuit of Gratton. They figured Brind'Amour (coming off a 27-goal, 59 point season) could switch to left wing or else move down to center the third line. The defensively-suspect Prospal was also slated for a move to wing.

The Flyers' crafted their offer-sheet to Gratton to be as front-loaded as possible. The Tampa Bay franchise was having severe cash flow problems and some were unsure if certain absentee members of the group of wealthy Japanese businessmen listed among minority owners of the team even existed. The team was officially put up for sale in December 1996.

Lightning president and general manager Phil Esposito knew that he had no way to come up with enough upfront money to match the Flyers' offer sheet within the required one-week timeframe. Espo may not have had the money, but he had a couple tricks up his sleeve.

Esposito protested the offer sheet to the NHL, asking the league to overturn it on the basis that the Flyers failed to comply with a league rule requiring Philadelphia to provide Tampa Bay with a complete, legible copy of the offer sheet to review. Esposito claimed that the print on the faxed copy Philadelphia provided was too smeared and blurry to be read.

Several hours after receiving the Flyers' offer sheet, Esposito traded Gratton's rights to the Chicago Blackhawks in exchange for Ethan Moreau, Keith Carney and Steve Dubinsky. Chicago had been offering the trade package for several weeks, and Esposito completed the trade without telling the Hawks that Philly had already signed Gratton to an offer sheet (which was filed with the league at 10:05 PM and had not yet been announced publicly).

Esposito claimed that the deal with Chicago had actually been consummated about 30 minutes prior to receiving notification of the Philadelphia offer sheet. However, due to the confusion over the illegible contents of the fax the Flyers sent, the trade to Chicago was not filed with the NHL until about three-and-a-half hours after the offer sheet was filed.

On Aug. 15, some 11 days after the initial offer sheet was filed with the NHL, the league ruled that the Flyers had met all required obligations to make the contract valid. If the copy the Flyers faxed to Tampa was too blurry to read, it was the obligation of the Lightning to promptly request a clearer copy.

As such, the trade to Chicago was invalidated. League rules prohibit trading an offer-sheeted RFA's matching rights. The league found no evidence that the trade with Chicago had been completed before the offer sheet.

As a result of the ruling, the one-week clock started ticking on Tampa matching or declining the offer sheet from Philadelphia. Esposito publicly claimed that he had secured the means to match the offer sheet, although many in the NHL (including the Flyers) were highly skeptical that Esposito had suddenly come up with the $9 million signing bonus due to Gratton within one week of signing the offer sheet.

Nevertheless, Flyers president Ed Snider instructed Clarke to settle the matter by making an overlapping trade with the Lightning in exchange for their agreement not to match the offer sheet. On Aug. 21, they reached a final agreement.

Tampa Bay agreed not to match the offer sheet and receive the Flyers' first round picks in 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001. The picks were then immediately returned to Philadelphia in exchange for first-line right winger Mikael Renberg and defenseman Karl Dykhuis.

Unfortunately for the Flyers, the Gratton acquisition ended up creating more headaches than it solved. The team's big-picture plan was to:

Unfortunately, the plan did not work out. Zubrus wasn't ready to be a top-line player (even with Lindros and John LeClair as his linemates), and his spot was eventually taken by Klatt -- who nevertheless slumped from 24 goals to 14.

After Prospal got off to a poor start, Brind'Amour was moved to second line left wing. Brind'Amour was still unhappy about playing out of his preferred center position, but accepted the move. Prospal briefly became the third-line center but struggled defensively (minus-10 in 41 games), got injured and was then traded to Ottawa along with Falloon (5 goals, 12 points in 30 games) in exchange for Alexandre Daigle.

Gratton did his best to fit in with his new club, but struggled to live up to the contract. In addition, there were players in the locker room who privately grumbled that the well-liked Renberg had been given something of a raw deal. The Swede had uncomplainingly attempted to played through a severe sports hernia in 1995-96 and, the next year, dealt with a gruesome facial cut as well as foot injury that needed off-season surgery in the summer of 1997.

Within a year of the trade, Clarke was already trying to lay groundwork to bring Renberg back to Philly, although the player continued to have injury issues in Tampa.

Gratton scored a goal in his first regular-season game as a Flyer. But then he went the next 15 games without a goal, going pointless in 11 of the games. In late November, the Flyers shook up the lines. LeClair was moved off Lindros' line for the better part of two months, and was placed on Gratton's line.

LeClair played some of the best hockey of his career in 1996-97 and he didn't skip a beat with the change from playing with Lindros to playing with Gratton. The line change got Gratton going for awhile, although he hit the skids again in January. Gratton got hot again just before the Olympic break and played well in the games immediately following the break. But then he staggered down the stretch until the final week of the season.

Brind'Amour moved up to play left wing with Lindros at even strength,and then later ended up moving back to center when Lindros missed 18 games with the first diagnosed concussion of his Flyers career. With Otto struggling to stay healthy, the Flyers ended up acquiring well-traveled center Mike Sillinger to boost the club's center depth. Sillinger ended up providing a decent boost (11 goals, 22 points in 27 games) to the team.

Gratton's final stats for the season ended up looking respectable -- 22 goals, 62 points. He dressed in every regular season and playoff game. Nevertheless, they were largely hollow numbers. A large percentage of his points came during the time he had LeClair on his line, but he closed the season strong with other linemates.

Nevertheless, many Flyers fans complained that Gratton disappeared in big games and rarely delivered when it counted. There was some evidence to back that up. According to the Stats Inc 1998 Yearbook, Gratton came away with a goose egg for the entire 1997-98 regular season in their "clutch goals" category. However, the book's definition of a clutch goal was rather narrow, being limited only to tying, go-ahead or two-goal insurance tallies in the third period. In reality, a clutch goal can happen any time a player scores at a juncture when a goal is sorely needed.

Gratton did score one undeniably huge goal in the playoffs. He notched the game-tying goal in the third period of Game 1 of the Flyers' first-round playoff series with the Buffalo Sabres. Unfortunately, two shifts later, Gratton committed a defensive gaffe that directly contributed to Donald Audette scoring the game-winning goal. Once again, he had gone from hero to scapegoat in the blink of an eye.

Before the 1998-99 season, Roger Neilson made a key lineup switch. He restored Brind'Amour to a full-time center role and moved Gratton to Brind'Amour's left wing on the second line. Now it was Gratton playing out of position, and unhappy about it.

Gratton struggled out of the games. In 26 games, he only scored one goal. The lone tally, scored at the 19:26 mark of the third period, closed out a 6-2 home win over Vancouver on Nov. 29, 1998. On Dec. 12, Gratton's Flyers career was over.

In a reversal of the initial deal, the Flyers traded Gratton back to Tampa Bay in exchange for Renbeg. The deal also sent Daymond Langkow to Philadelphia and Sillinger to the Bolts. Later that month, the Flyers brought Dykhuis back from Tampa in a separate deal. On Dec. 28, the Flyers sent Petr Svoboda to Tampa in exchange for his former defense partner from the 1995-96 and 1996-97 seasons.