All Charlie Coyle really wanted to be was a hockey player at Weymouth High School.

He grew up in a hockey family in a hockey city in a hockey state. An older cousin in the family, Bobby Sheehan, became the first American player to win the Stanley Cup in 1971 with the Montreal Canadiens; another, Tony Amonte, is in the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame.

Closer to home, his father, Chuck, played for Weymouth South High School (back when there were two schools), earning league MVP honors, and went on to play at Salem State University before becoming a coach in his hometown in the southern suburbs of Boston.

When Charlie and cousins like Tim and Trevor King went in the driveway and played around, sure, they thought about being Boston Bruins and skating in front of roaring fans in Boston’s TD Garden. But more realistically, they were preparing to wear the maroon and gold of the Weymouth Wildcats.

“As a young kid, you just want to be like your dad and want to be a good high school player in the Boston area,” Tim King said.

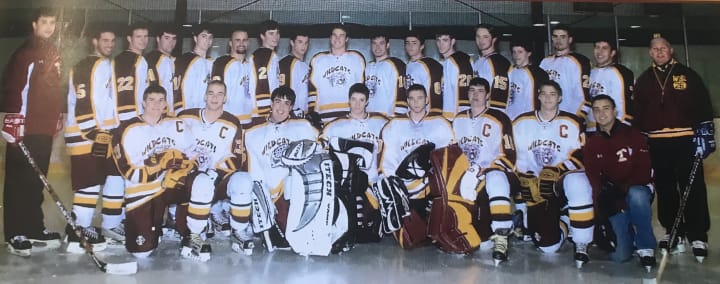

Under Chuck’s tutelage – and with help from the closeknit hockey community in Weymouth – and plenty of hard work, Charlie achieved that goal as a freshman, earning a spot on the varsity squad. Not only that, he was a contributor on the most successful Wildcats team of all time, making it all the way to the state championship game in a shocking run.

If that had been where it all ended for Coyle, he probably would have been more than satisfied, but he went much further than that. From Weymouth, he went to Thayer Academy, then Boston University, then the Minnesota Wild, his hometown Boston Bruins, the Colorado Avalanche and now the Columbus Blue Jackets.

Tomorrow, Coyle is set to play in his 1,000th NHL game when the Blue Jackets host Dallas, joining a club of just over 400 players to reach the milestone. It’s an accomplishment that carries a lot of weight in the league because of the consistent excellence and career longevity it demands.

And it all started with those driveway games that turned into high school success back in Weymouth.

“You always try to have high expectations for yourself and work as hard as you can and hope you get a little lucky along the way,” Coyle said. “I’ve had really good support – good coaches, teammates, parents, sisters, everyone around the community in Weymouth and beyond. It all helps. It’s not just me. I always keep that in mind.”

From his immediate family to an extensive network of cousins to the entire Weymouth community, those back in his hometown are proud of Coyle and ready to celebrate the latest accomplishment in a career full of them.

“It’s so exciting to see it,” Trevor King said. “I think there are a couple people in our family that always knew he was gonna be in the NHL. Everyone works for it, but I don’t know, maybe eight out of 10 guys in the NHL have God-given ability and maybe two out of the 10 don’t have it and they completely need to work for it. I think Charlie does have some God-given ability, but he’s on the other side.

“He puts so much time into everything. There was a hockey stick in his hand every day in the driveway working on shooting, stickhandling and all that stuff, so I’m not surprised he’s at 1,000 games. He’s a workhorse. He doesn’t take days off, ever. Nothing surprises me with Charlie.”

From ‘Skinny’ to Star

When Coyle first stepped into The Dungeon, the weight room where Weymouth High School athletes train under Pat O'Toole, the longtime strength and conditioning coach had a nickname for him.

"Skinny."

Coyle was all of 5-foot-3 and 114 pounds as a seventh-grader, and it’s fair to say he looked a bit out of place at first.

“He came into the room, and just imagine he’s with all the football players and all the high school hockey players and everything,” O’Toole said. “He was so determined to maximize what he could in hockey, so he came in and he worked his butt off for me. That was a big asset for him.

“Probably the biggest praise I could have for him is he’s one of the people that no matter how hard the work was, he stayed until the end. A lot of high school kids will take off and want to get out early, but Charlie was always the last one there.”

That might not be a surprise given the work ethic he inherited. The Coyles were a working class family, and Coyle's first summer job including working with his father in a warehouse that required a 20-minute bike ride to work each way. He brought the same dedication to his hockey preparation, spending hours upon hours working at the game and studying it.

“Oh yeah, it was 24/7/365,” Trevor King said. “I was the kind of kid that played video games – hockey and Madden – but he would put a time cap on it. It would just be, he has to make time to go work out, go shoot pucks. He’d be on YouTube watching film of guys. Pavel Datsyuk was one of his favorite players. It was hockey, hockey, hockey. We would do nothing but hockey, and he wouldn’t have it any other way.”

O’Toole might not have been too impressed by Coyle’s physique when he first arrived in The Dungeon, but he developed an immediate respect for his work ethic. And when you think about it, that’s the attitude you have to have. Kids all across the world dream of making it to the NHL, and while there's no certainty that just hard work will get you there, there is a guarantee that not giving your all will keep you from becoming one of the best of the best.

“I often wondered, I said, ‘Charlie, why did you work so hard?’” O’Toole said. “He said, ‘There might be somebody in the world that’s working harder than me, and I don’t want that to happen.’ He would go out of his way to make sure he did everything possible.”

That’s exactly what Coyle says looking back. All those minutes spent in the driveway or watching highlights of the league’s top players were part of his dedication to maximizing his potential. He never knew if he’d play one game let alone 1,000, but he was going to give it everything he had.

“I don’t know if I felt it was possible,” Coyle said of having such a long NHL career. “It’s just, that’s what I wanted to do, so I’m sure like a lot of guys, you do everything you can. You start to realize how many other hockey players there are in your state and your country, around the world. It’s like, man, how many opportunities, how many spots are there to play in the NHL and stay every year?

“Once you start realizing that more, I don’t have a crystal ball. I don’t know what everybody else is doing, how they’re training and how they are. I don’t know where I compare fully, so I have to do what I can to put in the work and trust that it’s good enough.”

A Memorable Run

Massachusetts is a hockey state. The Bruins have a devoted, loyal following, not to mention the type of historic success that sustains a massive fanbase. Ten Division I schools in the state sponsor hockey, with the four Boston-based schools that comprise The Beanpot leading the way with 11 combined NCAA championships. And high school hockey has a long and storied history, with a state championship dating back to 1943.

That’s a lot of institutional history, and in a city like Weymouth, the team is a point of pride for the blue-collar community of around 60,000 residents on the state's South Shore.

Just look at 2007 when Weymouth earned the nickname “The Public Nuisance.”

At the time, the Super Eight tournament crowned the state's best team, and it has traditionally been dominated by Catholic schools. In 2007, Weymouth entered with a 19-1-0 record but earned the No. 5 seed behind No. 1 Catholic Memorial, No. 2 St. John’s Prep, No. 3 Boston College High and No. 4 Malden Catholic.

Despite the record, not much was expected of Weymouth – another public school, Reading, lost all three games and was outscored 17-7 that year – but the Wildcats surprised observers and delighted the town by making it all the way to the championship game.

"In my years of being associated with the high school – which is 35 years, something like that – it was probably the greatest experience,” O’Toole said. “The whole town, it was unbelievable. Everyone kept talking about the games. Everyone kept going.”

Weymouth knew it had a chance to have a special season going on, with a senior-laden group led by Tim King. Coyle was an undersized freshman who had played on local AAA teams, but he had enough potential to find himself on the varsity roster, generally lining up as the team’s third line right wing.

He totaled 12 points as the season went on, mostly assists, until one memorable goal in the opening game of the Super Eight against Malden Catholic.

“Charlie had only one goal at that point, but I knew how good he was,” Trevor King said. “It’s men against boys, and he was the boy in that. So they’re in the playoffs, they’re losing to Malden Catholic, who is good, and Charlie is going one-on-one with a defenseman in the third period. Charlie hits a complete clean toe drag, breaks the kid’s ankles, goes down and scores, and the place was rocking. It was pretty cool because a lot of people counted Charlie out as a freshman, and he saved the day. The whole crowd was chanting, ‘He’s a fresh-man.’ That was probably his first big moment.”