In the Rosemont section of east Montreal in the mid-1950s, Hall of Fame goaltender Jacques Plante sometimes came by to visit the home of his sister, Thérèse. Whenever word spread that the hockey superstar was coming, Thérèse's neighbor's son and his friends ran across the street and hid behind the bushes to try to catch a glimpse of their idol.

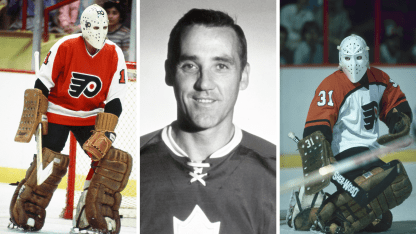

A Special Bond: Plante, Parent and Pelle

Flyers contributor Bill Meltzer examines the connection of the three goaltenders

By

Bill Meltzer

philadelphiaflyers.com

The youngster, an aspiring goaltender, daydreamed of someday becoming friends and teammates with Plante. The child's name: Bernard Marcel Parent.

Years later, Plante became Parent's NHL teammate and mentor with the Toronto Maple Leafs. In 1977, Hockey Hall of Fame inductee Plante became the first goaltending coach in Philadelphia Flyers history. He served as Parent's confidant and sounding board for the remainder of the player's career.

In the working-class south side of Stockholm in the early to mid-1970, a young aspiring goaltender adopted the Philadelphia Flyers as his favorite National Hockey League team and came to idolize Flyers' superstar goaltender Parent; winner of back-to-back Vezina Trophies, Conn Smythe Trophies and the Stanley Cup championships of 1973-74 and 1974-75.

The Swedish youngster, who doodled Flyers logos in his school notebook and wore a Parent-style mask (complete with Flyers logo decals on the crown and the temples of the mask) even when playing for the local Hammarby hockey team, daydreamed of someday becoming Parent's successor in Philadelphia.

The young goaltender's name: Göran Per-Eric Lindbergh, better known as "Pelle."

Years later, following a career-ending eye injury, Parent succeeded Plante to become the second goalie coach in Flyers team history. His prized pupil was Lindbergh, and the two men developed such a close bond with one another that Lindbergh often referred to Parent while in Sweden as "my dad in the United States."

No one was happier for Lindbergh winning the 1984-85 Vezina Trophy than Parent, who worked side-by-side with him through the ups and downs of his NHL career. Fittingly it was Bernie himself who presented Lindbergh with the award on national television.

Four months later, after Lindbergh perished in an automobile accident in the wee hours of Nov. 10, 1985, a grief-stricken Parent eulogized Lindbergh in a pregame memorial at the Spectrum. Parent also traveled to Sweden to attend Lindbergh's funeral, visiting his parent's Stockholm apartment that was Pelle's childhood home.

This is the story of how the relationships between Jacques Plante and Bernie Parent and of Parent and Lindbergh came full circle in ways that were both heartwarming and heartbreaking.

A LEGEND IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD

Bernie Parent's older brothers, van and Jacques Parent were the ones who got Bernie started in hockey. From an early age, he played street hockey, wearing boots and using a tennis ball for a puck. At the age of seven, his parents gave him his first pair of ice skates for Christmas. Yvan and Jacques would work with their younger brother in the backyard. Initially, he wanted to be a forward.

Because Bernie had good balance but was a poor skater, Yvan suggested he try goaltending. Bernie was excited about the idea at first because his hockey idol was legendary Canadiens goaltender Jacques Plante. He soon changed his mind about goaltending, though, because he hated wearing the goalie equipment. He felt clumsy and had a hard time moving around in it. Yvan told him to stick with it.

Yvan Parent coached a local bantam team. Bernie was recruited to play goal, using borrowed equipment (it was not until he was twelve that he finally got goalie gear of his own). Although it took a while for Bernie to fully embrace the pressure that is part of being a goalie, he eventually came to excel at the position.

Bernie idolize Montreal Canadiens goalie Jacques Plante throughout his youth. For a time, Plante's sister, Therese, lived next door to the Parents (who had moved when Bernie was ten to 1885 Bruxelles Street, a short distance from the house where he had spent his early childhood). Bernie always dreamed of meeting his idol but never worked up the nerve to approach Plante directly.

Little did Parent suspect at the time that his fantasies of being tutored by Plante would someday come true.

Parent, of course, went on to star in junior hockey for the Niagara Falls Flyers and broke into the NHL with the Boston Bruins before the Flyers selected him with their first-round pick in the 1967 Expansion Draft.

On January 31, 1971, a three-way deal was worked out with the Flyers, Maple Leafs, and Bruins. Parent went to Toronto. In return, the Flyers received journeyman goalie Bruce Gamble, a pair of first round picks in 1971, and, most importantly, a Bruins scoring prospect by the name of Rick MacLeish. They also received two first round picks in the 1971 draft.

PLANTE-ING THE SEEDS OF GREATNESS

Parent soon realized that there was a bright side to the trade. Going to Toronto afforded him the chance to finally play alongside his idol, Plante, who, at 41, was at the end of his storied career.

Plante was not always the easiest of people to get along with. His personality was diametrically opposite to Bernie's. Plante had long been something of a loner in the hockey world. But he took a strong liking to Parent.

Perhaps it was the fact that Bernie played such a similar style in the net. Perhaps it was the realization that despite the fact he was one of the better goalies in the NHL, Parent's true potential was still untapped and Plante was in position to help him.

Whatever his reasons may have been, Plante quickly took Parent under his wing. Under Plante's tutelage, Bernie steadily transformed from a good NHL goalie into a great one. Plante helped Parent make subtle adjustments to his game and to overhaul his mental approach to the game. Parent became a more focused, more confident, goaltender.

After spending a season and a half in Toronto and one in the World Hockey Association with the Philadelphia Blazers, Parent returned to the Flyers. On the afternoon of June 22, 1973, tears flowed once again at the Spectrum. This time, they were tears of happiness. The Flyers sent Favell and a first round pick to the Leafs in exchange for Parent and a second round pick. The mood brightened considerably when the announcement came that Parent had signed a multi-year deal with the Flyers.

Back-to-back Vezina Trophies followed for Parent, along with two straight Stanley Cup championships and three straight trips to the Cup Finals for Fred Shero's Flyers. Parent captured the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP in both 1974 and 1975. He often credited the mentorship of Plante for helping him unlock his full potential on a game-in and game-out basis.

Parent dealt with injury problems during the 1975-76 season. While still among the NHL's upper echelon of goalies, he could not quite perform to the same standards in 1976-77 and the Flyers got swept by the Boston Bruins in the 1977 Stanley Cup Semifinals (each of the first three games were one-goal margins before Boston closed it out with a 3-0 victory at the Garden). Parent felt that his own performance was not up to par that season.

The Flyers decided to hire the now-retired Plante as a goaltending instructor to work with Parent and Wayne Stephenson. Primarily, though, Plante was brought on board because of his strong relationship with Parent. It worked. Parent had a bounceback season (2.22 goals against average, seven shutouts and a gaudy 29-6-13 record). However, the Flyers once again lost to Boston in the Stanley Cup Semifinals, this time in five games. Hockey Hall of Fame coach Shero departed after the season. Midway through the 1978-79 season, Parent suffered an eye injury that proved to be career-ending.

A SWEDISH PRODIGY

Before the 1979 NHL Draft, Bernie Parent had no idea who Pelle Lindbergh was but Lindbergh certainly knew of him. Lindbergh became a Flyers fan in adolescence, at first simply because he liked the Flyers' logo.

At age 15, he saw Parent play for the first time when he watched a highlight movie of the 1974 Stanley Cup playoffs. Lindbergh was instantly enamored with Parent's stand-up style and ability to make tough saves look routine. He convinced his father, Sigge, to purchase both the 1974 and 1975 playoff films and watched them over and over on a projector at home.

Parent became Lindbergh's favorite player. Pelle wore the same style mask as Parent, right down to adding Flyers logo decals to the mask years before Lindbergh was drafted by Philadelphia. More substantively, Lindbergh studied every nuance of Parent's technique in goal. Off the ice, Pelle went around telling anyone who would listen that he'd someday become the starting goaltender for the Philadelphia Flyers.

Lindbergh was a prodigy as he rose through the ranks of domestic and international hockey. He won Best Goaltender honors at the World Junior Championships, became the youngest goaltender to debut for Team Sweden's men's national team, and backstopped Tre Kronor to the 1980 Olympics, approximately six months after the Flyers selected him in the second round of the 1979 NHL Draft.

It was during Lindbergh's first visit to Philadelphia that Parent met him for the first time. Somewhat starstruck, Lindbergh was quiet and didn't say much. It was not until Bernie saw Team Sweden play in the Olympics, however, that he actually saw Lindbergh play for the first time and realized just how much Lindbergh had studied him from afar.

"My God, it was like watching myself," Parent said in 2008. "Same style, same mask, same everything."

Parent served as a training camp goaltending instructor and special assignment scout for the Flyers the first few years after his retirement as a player. Plante continued to travel occasionally from his residence in Switzerland, and retained the title of Flyers goaltending instructor through the 1981-82 season. Thereafter, Parent became the Flyers' goaltending coach from the 1982-83 season until 1994.

GOOD TIMES - BAD TIMES

Both Plante and Parent were on hand to watch the goaltenders during Lindbergh's first NHL training camp. There were nine goalies in all at the start of camp, including incumbent Flyers starter Pete Peeters.

One of the first pieces of advice that Lindbergh received from Parent was that he needed to rely less on his reflexes and more on cutting down the angles. They worked on adjusting his play around the crease.

"You're a great skater, much better than me," Parent says to him in their first

session together. "You're gonna have no problem moving when you need to, but

right now you're back a little too deep. If you come out and cut down the angle a little more, even if the pass goes across, you're gonna have a good chance to recover with the way you move."

In 1980-81, as a rookie for the American Hockey League's Maine Mariners, Lindbergh swept all of the league's awards for which he was eligible. Lindbergh won the Les Cunningham Award (league MVP), the Red Garrett Memorial Award (Rookie of the Year) and the Hap Holmes Award (top goaltender). In the 1981 playoffs, Lindbergh backstopped the Mariners to the Calder Cup Finals before being slowed by a knee injury that affected his play in the final round.

As a Flyers rookie in 1982-83, Lindbergh played in the NHL All-Star Game and earned NHL All-Rookie Team honors despite being hindered in the second half of the season by a broken wrist suffered in the Flyers' 5-1 exhibition game loss to the Soviet national team at the Spectrum on Jan. 6, 1983.

Lindbergh never really regained his form the rest of his rookie season after returning from the wrist injury. He and the entire Flyers team stumbled badly in the 1983 postseason, getting ousted quickly in the first round by the New York Rangers.

The following year, Lindbergh struggled mightily with his both timing and confidence for much of the 1983-84 season. At one point, the Flyers even briefly sent Lindbergh back to the AHL to rediscover his game.

Goalie coach Parent was with his pupil every step of the way, even accompanying Lindbergh to Springfield to work directly with him while he played for the Indians. The two men had heart-to-heart talks about Lindbergh's crisis of confidence, and Parent shared freely of the wisdom he'd gained about working through adversity from a mental standpoint. Much of the advice had come from things Plante once told Parent.

"It's not the first goal you give up that makes you tough to play against," Parent said to Lindbergh. "A lot of times, it's that second goal. When you give up one didn't like, you wanna crawl under the ice. You're pissed off. It's normal. But you can't let that control you."

It took time for Lindbergh, as is often the case for young goalies (including Parent in the early years of his NHL career) to master the mental and emotional side of playing his position. He still fretted at times over stoppable goals and struggled when he wasn't playing.

However, in 1984-85, Lindbergh achieved his breakthrough.

LINDBERGH WINS THE VEZINA

Lindbergh was nothing short of brilliant during the 1984-85 season. The young Flyers were an exciting and gritty team, always playing on the raw edge of emotion. As a result, however, outside of a few key team leaders who helped keep things on an even keel, they were also a bunch that was at risk of losing its composure.

Rookie head coach Mike Keenan drove the team relentlessly, and spared no feelings in the way he challenged his players to bring out their best. Some players handled it better than others. When Lindbergh needed someone to turn to, he turned to Parent and to sports psychologist Steven Rosenberg.

On many nights, Lindbergh was the glue that held the team together, getting them over the hump when momentum started to turn against them. More important than raw stats were all the key saves that Lindbergh made that year. He gave the team a chance to win almost every night.

As great as he was in the regular season, Lindbergh cranked up his game even further in the 1985 Stanley Cup playoffs. Arguably, the emerging superstart goalie was the number one reason the Flyers broke free from their post-1980 playoff doldrums and made it to the Stanley Cup Finals. Philadelphia won Game 1 against the otherworldly Edmonton Oilers squad before succumbing to their superior talent.

After the season, Lindbergh received two special honors. On June 13, 1985 at the Metro Convention Center in Toronto, Pelle was announced as the winner of the Vezina Trophy. The trophy was presented to him by Parent. Lindbergh was also a finalist for the Hart Trophy, losing out to Wayne Gretzky, and was named a First-Team NHL All-Star (the second Swede to receive that honor, after Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman Börje Salming became the first).

"The man I really want to thank is the guy standing to the left of me, Bernie Parent," Lindbergh said in his Vezina acceptance speech. "He taught me everything I know, to play hockey in America. Thank you, Bernie!"

Parent proceeded to warmly hug Lindbergh; a frozen-in-time moment of the highest point of their personal friendship and professional working relationship. After the awards ceremony, Parent largely stayed in the background to allow Lindbergh the chance to bask in the recognition of his achievement.

"That night in Toronto was the finest memory I have from the time with Pelle. I was even happier and prouder than when I won the Vezina. I saw all the hard work that went into it, and I saw Pelle make his dreams come true. He was so determined," Parent recalled in 2009.

"We didn't say much to each other during the night, but to see him walk up from the floor to the stage, and look him in the eye and hand him the award and give him a big hug, it really said more than any words we could say to each other."

Several times during the night, we looked over to each other and caught each other's eyes. We both knew what it took to get there. He had to battle for it and get through some really tough times.

"When it came time to give interviews, I went off the side. It was his night, and he earned it. I was just glad to watch him a little in the hall and see how pleased he was."

TEARS OF MOURNING

Lindbergh and the Flyers actually got off the better start in 1985-86 than they had the previous year. The team looked unstoppable, dismantling one opponent after another. The Flyers' 26-year-old goaltending star was about to sign a multi-year contract extension that would have made him the highest-paid goalie in the league and one of the highest-paid players at any position. The contract was set to be signed by mid-November.

The fairytale story shattered shortly before 5 a.m. on Nov. 10, 1985.

Leaving a late-night team celebration in the after-hours bar at the Coliseum in Voorhees, Lindbergh was left brain dead after he drove his souped-up Porsche into a wall where it met the steps of a school in Somerdale, New Jersey.

The next day, after Lindbergh's fiancee, Kerstin, and his parents agreed to donate his organs, they said their final goodbyes. The ventilator that kept him breathing was turned off.

On Nov. 14, 1985, before a game at the Spectrum against the Oilers, the Flyers held a memorial ceremony for Lindbergh. Parent had the agonizing task of delivering a eulogy for a young man who'd come to regard him as a father figure as well as his coach.

Clad in a dark blue suit, white shirt and dark red tie, Parent approached the podium. Several times, he had to pause to compose himself as he addresses the crowd.

Midway through the eulogy Parent said, "The papers have said that I was his hero. But I wish I could tell you how much I admired him. I wish I could have only told him this; told him how much I admired him and how much I cared about him."

Parent's lip quivered and he brushed away a tear. The Spectrum crowd cheered to give him the strength to continue. Parent took a deep breath and then resumed speaking.

"A goalie stands on a very lonely island, and I'm grateful that I was able to share some of that island with him, but for too brief a period. Pelle Lindbergh had become, without question, one of hockey's greatest goalies. When death defeats greatness, we mourn. And when death defeats youth, we mourn even more."

At the end of his speech, Parent could only manage to say a few words at a time as the emotions welled up inside him. Speaking in a low, staccato voice, Parent concluded with, "Pelle, you will always live in our hearts. Pelle we miss you."

A PRIVATE MOMENT BRINGS INNER PEACE

The Flyers won the game, 5-3. Afterwards, a contingent of Flyers traveled to Sweden to join with Pelle's family for his funeral in Stockholm.

Parent was welcomed into Lindbergh's childhood home. In the family's living room, among the family photographs adjacent to the couch, there was a framed photo of a beaming Pelle and Bernie standing side-by-side.

The photo was taken at the NHL Awards ceremony a few months earlier. The framed picture would remain in the same place until after the passings of Pelle's parents, Sigge and Anna-Lisa Lindbergh. Parent has also kept a print of the photo over the years.

After gathering with the family in the living room, Parent was shown to Pelle's childhood bedroom; still adorned with hockey-related photos, trophies, plaques, Pelle's teenage music collection and his hockey books that included a copy of Bernie's as-told-to autobiography (one of the first English-language books that Pelle ever read).

Bernie Parent was then left alone in the room and invited to stay as long as he wanted.

"I had the chance to be alone in Pelle's room for a few minutes, and it was a very, very special moment. The room was full of Pelle's private memories, but it didn't feel strange to be there. I felt at home. Well, this is hard to explain, but I got a warm feeling in there. I felt like Pelle was talking to me. He was saying that everything would be good, everything was OK, and I could go on," Parent recalled in 2008.

November 10, 2020 marked the 35th anniversary of Pelle Lindbergh's passing at age 26. February 27, 2021 will mark the 35th anniversary of the cancer-related passing of Bernie Parent's own childhood idol and subsequent goaltending mentor and close friend, Jacques Plante. Plante was only 57 years at the time of his death.