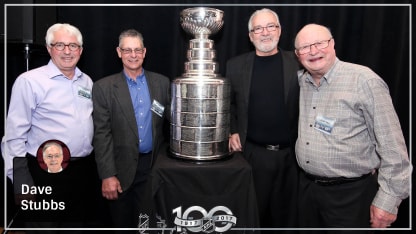

TORONTO --The photographs had been taken behind the closed doors of a hotel conference room on New Year's Eve shortly after 7 p.m., the fabulous stories bouncing around as crazily as a warm puck.

And now these five hockey icons were preparing to walk down the hallway with NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman to a dinner being held in their honor, and that of 28 more of the League's greatest players of all time.

Hockey legends enjoy legendary night

NHL.com goes behind the scenes at New Year's Eve dinner honoring League's greats

"I've had two NHL presidents call me at home my whole life," Leonard "Red" Kelly told his host. "Clarence Campbell, and now you."

"I assume," Commissioner Bettman replied with a chuckle, "that you were in trouble when Clarence called you?"

Kelly nodded, to the laughter of everyone.

There would not be a fine discussed when Kelly recently picked up the phone to hear the Commissioner inform him he had been named to

the list of the 100 Greatest NHL Players

. Every living player on the list received a similar call, as did a family member of the players selected who no longer are with us.

© Picasa

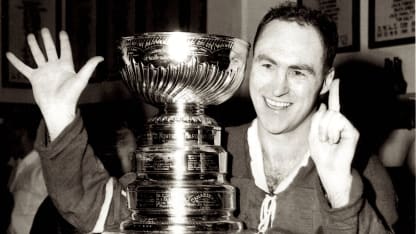

Toronto Maple Leafs' Red Kelly celebrates his sixth of what would be eight career Stanley Cup titles.

Thirty-three names, each a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, would be publicly announced on New Year's Day at the 2017 Scotiabank NHL Centennial Classic. These men had starred in the first 50 years of the NHL, between 1917 and 1966. Sixty-seven more legends, who played between 1967 and 2017, will be introduced Jan. 27 at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles as part of the Honda All-Star Game Weekend.

But on New Year's Eve in a Toronto hotel ballroom, the Stanley Cup standing as a sterling sentry at the front of the hall, the two-plus-hour celebration over a private dinner for roughly 100 people was quiet, casual and, for many, profoundly emotional.

Nine men on the list of 33 are still with us, and five were on hand New Year's Eve. Kelly, senior-most of the group at age 89, was joined by goaltender Glenn Hall and forwards John Bucyk, Alex Delvecchio and Dave Keon.

The night before, goalie Johnny Bower, 93, had attended a reunion dinner of the Toronto Maple Leafs 1967 championship team. Earlier on New Year's Eve, he had dropped by the 2017 Rogers NHL Centennial Classic Alumni Game, so he took a pass on dinner to rest up for his public appearance on New Year's Day.

Fellow icons Ted Lindsay, Frank Mahovlich and Henri Richard were unable to attend.

A little from the dining room then, a remarkable, unforgettable evening which for this observer began at the table of Glenn Hall, his son, Pat, and daughter-in-law, Debbie, and Bob and Nancy Geoffrion, son and daughter-in-law of the late Bernie "Boom Boom" Geoffrion.

Toronto Maple Leafs goalie Turk Broda with the Stanley Cup in the foreground, taken at the New Year's Eve dinner.

\\*

Many "unknown number" calls come to Mr. Goalie at his farm in Stony Plain, Alberta, and Glenn Hall handles most of them the same way: He ignores them, or he lifts the receiver just long enough to hang up.

So it was that Hall's phone rang at 7 a.m. one morning not long ago, stirring him from his slumber.

"I answered this one and before the caller could speak, I gave him hell," Hall said. "I said, 'You damn telemarketers, why are you calling me at 7 in the morning?' I was about to hang up when Mr. Bettman identified himself.

"Well, I apologized - a little bit," Hall added with a grin painted in a subtle shade of mischief. "But I still wondered whether it was one of my friends pulling a fast one."

A shy man in public but one who will stitch together a quilt of fantastic stories when among friends, Hall was just warming up.

"No, I never fished the puck out of my net when someone scored," he said in his slow, worth-the-wait drawl. "Why would I? I didn't put it there. …

"In Detroit, if we'd had a bad period, Alex Delvecchio would race into the dressing room and eat a bunch of oranges and throw the peels in the doorway," he said. "When [general manager] Jack Adams would come in to give us hell, he'd hit the peels and go flying. …

"It's such a thrill to be in this room with so many of my friends." Then, with a smile: "And it's amazing that I'm the only one who hasn't changed. The rest of them have gone downhill quite severely. …

"My first year in St. Louis [in 1967-68], I always sat in the last row of the bus, on the window, opposite the driver's side. One day, I get on the bus and there's [rookie] Tim Ecclestone, sitting in my seat. I walked back slowly and said to him, 'Rook, there are only two seats reserved on this bus: the driver's, and this one. You can take any one of the others.' "

And then Hall laughed.

"But in my last season [1970-71], I bequeathed that seat to Tim."

It didn't much matter. Ecclestone was traded in February 1971, before Hall retired at season's end.

\\*

There are very few stories Maurice Richard Jr. has not heard about his firebreathing father. The mighty Rocket's coal-black eyes and his single-minded propulsion from the blue line to the net terrorized goaltenders from the early 1940s until his retirement in 1960.

"My father would be honored to be on this list," said Maurice Jr., the Rocket's 1945 Stanley Cup ring - won the year of his son's birth - on his right hand. "He never thought he was so good, so great. He was very humble, he played hockey because he loved the game. He wasn't looking to be a big star."

Maurice Jr. attended the dinner with his sister, Huguette. It was the latter's birthweight of nine pounds that prompted Richard to ask his coach, Dick Irvin, to switch from the No. 15 he had been wearing to No. 9 for the 1943-44 season, a sweater he would make legendary in Montreal.

The Rocket died in 2000 after a battle with cancer, and his death brought all of Quebec to its knees to mourn the heart and soul of some of the Canadiens greatest teams, a man who unwillingly was a figurehead during an explosive time in the politics of the province.

"It took a lot of time for me to put my father's life in perspective," Maurice Jr. said. "With the years, I've read a lot of things about his career, I've met a lot of people and been told a lot of things. I'm 71 so I saw him play the last five, six years of his career, his last Stanley Cups.

"I remember my father when I was young. Every practice at the Montreal Forum, I was there with him, in the room with the players."

A lot of excuse notes written for teachers, surely?

"No, no, I didn't skip class that many days," Maurice Jr. said. "My father would not have liked that."

Canadiens' Maurice Richard photographs his family at the Montreal Forum in the mid-1950s. Maurice Richard Jr. is second from right in front of the net. (Photo courtesy of Montreal Canadiens)

\\*

They were late to the dinner, but Mark Howe and Marty Howe did not slip into the ballroom unnoticed. When you are two of the late Mr. Hockey's three sons, you are recognized most everywhere you go - especially in a room like this.

The brothers stood at one end of the hall, Mark with a plate of food, Marty sipping a beer, and above them a slide show featured a handful of priceless photos of Gordie Howe, whose passing not quite seven months ago is still sharply felt in the game and far beyond it.

"He'd like all of these people," Marty said, looking around the room. "I used to like going to the All-Star Game because they'd all be there. You'd go into a room and there'd be no one in there but the players, and they'd all be telling stories."

With a finger, Marty drew a line down one cheek. Then the other. Then across the chin, then the forehead.

"They'd tell him, 'Gordie, you did this to me.' 'You did that to me.' 'How about this one?' 'And this… I look better now than I used to!' " he said with a grin, having mapped out the valleys of scars that his rugged father might have left behind. "Even when I was taking Gordie around for appearances when we were older, I'd be hearing all of those things."

Gordie Howe's unfabricated love of people, from world leaders to the shy kids he met in the street, was something his sons knew better than anyone.

"Gordie had a tremendous sense of humor, his timing and his wit were incredible," Mark Howe said. "As he got older, people would be talking about Dad, about his health declining. He'd be halfway across the room and he'd say, 'My hearing is still plenty good.' He was more of a people person than probably anybody I've ever met.

"I've only met a couple people in my life who have that certain charisma and magnetism about them. People just flock to them. Everybody remembers when they met Gordie Howe. Marty and I hear it all the time, in email and in person. Everybody has their story. We were checking into the hotel and on the elevator, a guy of 60-something was telling us that he was 11 when he met Gordie out in Calgary. When somebody impacts your life that much when you meet them, they are a special person."

Would there be a single thing that Gordie might have cherished, more than any other, about his hockey life?

"He'd thank God that he got to play with his sons," joked Marty, Gordie having skated with Mark and Marty with the Houston Aeros of the World Hockey Association in the 1970s.

"He wanted to do that when we were little guys. We'd play [fundraising] games for the March of Dimes, against the Red Wings, and Gordie would play on our side so we'd be even. Those moments kind of spurred him on."

And then, no longer speaking in the past tense:

"He is just an amazing person, not a selfish person at all," Marty said. "He's not a 'me, myself, I' guy. He's the greatest teammate you'll ever have on a team. He's not a vocal guy, but he does things that most people don't do."

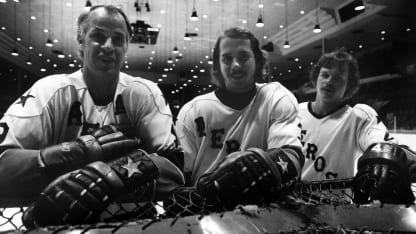

© B Bennett/Getty Images

From left, Gordie Howe, Marty Howe and Mark Howe of the Houston Aeros pose for a portrait.

\\*

One man who Gordie would have spent a great deal of New Year's Eve with, the Howe brothers said, would have been Kelly, a teammate and a dear friend.

Like Hall, with whom he played for the Red Wings, Kelly had a deep barrel of tales, many of them gathered in his wonderful biography "The Red Kelly Story," published last fall.

"When you grew up, hockey was what you admired," said Kelly, whose fan mail still arrives from around the world. "It's what you listened to, putting yourself in the sweater of the players you didn't see but only heard over the radio. Then, eventually, you saw them on TV and oh, the ability that some of those players had. To think that you would become one of them, be able to make it and be on one of those teams, and then win eight Stanley Cups… that was fantastic, what more could you ask? To end your career and say, 'Holy man, I've been part of it.' "

And then Kelly shared this gem:

"I was coaching the Pittsburgh Penguins in the early 1970s and Eddie Shack, who'd been a linemate in Toronto, was playing for me. Eddie came to me and said, 'Remember in Toronto about 10 years ago when you shot the puck from near the blue line and I put my stick up and got credit for the goal? I never touched the puck.'

"Without TV replays, no one knew. Eddie said, 'I needed the goal more than you. I had a bonus clause.' It seems he needed to confess."

Red Kelly at 2017 Scotiabank NHL Centennial Classic game.

\\\

You would hear Bernie Geoffrion before you ever saw him, his baritone voice booming as loudly as the slap shot he popularized in the 1950s with the thick, flat blade of his heavy ash stick.

Bob Geoffrion is cut from the same cloth as his late father, with a story and probably a song for every occasion, just like his old man.

"My dad would tell me, 'Son, as long as I owe you money, we'll never go broke!' " Geoffrion said brightly.

The hugely popular beer commercials Bernie Geoffrion starred in during the late 1970s and early 1980s were problematic in that the phrase "a third less calories" was one around which the Boomer couldn't quite wrap his French-Canadian tongue.

"After 35 takes, they finally had to dub in one word," Bob Geoffrion said, laughing. "How do you use the word 'turd' in a beer commercial?"

\\\

I was barely off the elevator, headed to the dinner, when an elegant woman took me by the arm. By night's end, with her son, Robert, Françoise Vezina Gagnon was steering me to her room upstairs.

There she spread out a priceless assortment of photos of her family and her late grandfather, Georges Vezina, the first great goaltender in the history of the NHL.

Just when you think you've seen all of the few photos that apparently exist of this hockey pioneer, Françoise offers you one of Georges and his wife, Marie-Stella Morin, taken on their wedding day of June 3, 1908. And then another of the couple's two sons, Jean-Jules and the younger Marcel Stanley.

The latter was born on March 31, 1916, and Françoise explains that Stanley got his middle name because he had arrived the night before Vezina had anchored the Canadiens to their first Stanley Cup championship, won against the Pacific Coast Hockey Association's Portland Rosebuds.

Left: Georges Vezina's sons Marcel Stanley and Jean-Jules, taken in the early to mid-1920. Right: Goaltending legend Georges Vezina and his wife, Marie-Stella Morin, on their wedding day on June 3, 1908.

\\*

"I don't think my dad ever knew how good his accomplishments were," Jerry Sawchuk said about his late goaltending father, Terry, a four-time Stanley Cup champion for the Red Wings and Maple Leafs. "He never liked the spotlight, but it would be hard to say that he wouldn't be satisfied with what he did to revolutionize the game."

It was with the Red Wings on Jan. 18, 1964 at the Montreal Forum that Sawchuk would pass his boyhood hero, George Hainsworth, to become the NHL's shutout king with 95. He would retire with 103, a seemingly invincible record until the New Jersey Devils' Martin Brodeur passed him in 2009 en route to 124 for his career.

"The 100th shutout, which he got with Toronto, was a big moment for my dad," Jerry said. "He was comfortable with the Maple Leafs. I remember watching it at home in Detroit on Hockey Night in Canada. I could see he was tearing up. I think that, and his four Stanley Cups, would be his big accomplishments, but that 100th shutout puck was huge. That took a whole career to get."

Jerry was a goaltender early in his own hockey life, and he recalled playing nets during a boyhood session of Gordie Howe's hockey school.

"We were going through the scrimmages, my dad was teaching, and I started getting into the butterfly, going down, letting my reflexes take over," he said. "My dad was an angle goalie, to perfection, and when he saw me going down a little before the shots, he let me have it in front of all the kids and coaches. 'Who do you think you are, Glenn Hall?' he yelled at me. 'Get back on your feet and cut down that angle.' So that's what I did."

It is going on 47 years since the Hall of Fame goalie's passing, and Jerry soon will commemorate his father's magnificent career with ink, as will Jerry's son, Jonathan, 29, who knows his grandfather only by his huge legend: they plan to have likenesses of Terry Sawchuk's iconic mask tattooed onto their arms.

Young Jerry Sawchuk is photographed with his goaltending father, Terry Sawchuk, then of the Boston Bruins, in the mid-1950s.

\\*

The late Jacques Plante was a brilliant, eccentric, trailblazing talent who backstopped the Canadiens to six Stanley Cup championships between 1953-60.

He would popularize the use of the mask when he wore one into a game on Nov. 1, 1959, his face torn open by a shot off the stick of the New York Rangers' Andy Bathgate.

Plante studied shooters years before scouting was in vogue, poring over his own notes the night before a game. He befriended the goalies of other teams, even other nations, simply because they were lodge brothers in the game's most difficult position.

Like Maurice Richard's son, it took Michel Plante some time to understand the enormous influence his father had on hockey.

"He was my dad, like someone else might have seen their dad who was working in a shop," Michel said. "He was innovating all kinds of stuff. As you grow older and see everything he put in and came up with, to improve the game as much as he did, I really came to realize what he did. It's quite an achievement. I'm very proud of what he did."

The simple family moments, more than the milestones, are what Michel cherishes most.

"I remember Christmas time, skating at the Forum with my dad and Jean Béliveau, Maurice Richard and the Canadiens," he said. "Being part of that family was something I truly enjoyed. My dad liked the NHL, the players and being with the families. To have all of these people here who are bringing the League to its 100th anniversary would be something very special for him."

Michel Plante, son of the late goalie Jacques Plante, with former Canadiens goalie Gump Worsley at the Montreal Forum on Oct. 7, 1995, the night the Canadiens retired Plante's No. 1. (Photo courtesy of Montreal Canadiens)

\\*

Indeed, Michel Plante's words were the thread that connected everyone in a New Year's Eve ballroom; different generations, long-time acquaintances and new friends celebrating the NHL's glorious past.

"If Dad were here today, he'd just love seeing old faces," Mark Howe said. "Gordie respected the honors and awards that he got, but he was all about people. What he'd enjoy most would be the NHL having put this function together so he could see some old friends and teammates."

He laughed.

"And maybe even some of the old enemies he had on the other side of the rink."