Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

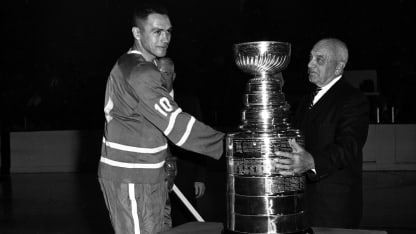

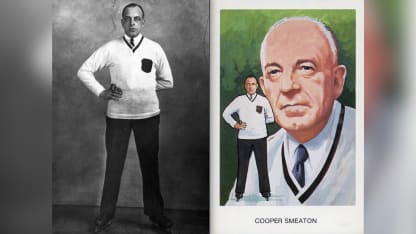

This week, Fischler returns to "Voices from the Past." His subject is James Cooper Smeaton, an iconic on-ice official who went from being a player to the father of modern officiating, a 1961 Hockey Hall of Fame induction and trustee of the Stanley Cup until his death Oct. 3, 1978, at the age of 88.

The 1976 interview originally appeared in Fischler's book, "Those were the days: The lore of hockey."

How did you become a hockey player?

"I was born in Ottawa, but my family moved to Montreal when I was 3 and that's where my hockey playing began. The Westmount Amateur Athletic Association had a team, and I earned a spot on defense, only in those days, at the turn of the century, it was called point. We won our share of championships and I got recognized for my play by hockey people at New York's St. Nicholas Arena, which then was the main hockey center in Manhattan. It was not far from Times Square and had several teams in a league. I suddenly realized that I was in demand."

What was attractive about the offer?

"The fact that I could play high-level hockey along with some very good players from Montreal and also get a job at the same time. Sprague Cleghorn and his brother, Odie, were the other (Montreal natives) who were invited to Manhattan by the New York Wanderers. There was no National Hockey League in those days, but top-notch players were given good jobs in the city, and we were getting paid pretty good money so we could enjoy life in a fast-growing New York."

What was it like to be a pro in 'The Big Apple?'

"We weren't exactly professionals by the later standards of the NHL because my hockey salary was being paid for by my other employer, the Spaulding Sporting Goods Company. Likewise, Sprague's salary was paid by the telephone company and Odie's by a Wall Street brokerage. The hockey was intense and that's why the Wanderers had us come down from Canada. Besides the Wanderers, the other teams were the St. Nicholas Hockey Club, the New York Hockey Club and one from Brooklyn called the Crescent Athletic Club. Also, collegiate teams played at St. Nick's and that's where the great American player Hobey Baker was the big attraction playing for Princeton. I loved New York and the whole setup there."

What made you leave to become a referee?

"I would have stayed on and played, but a serious family situation came up at home in Montreal and I had to return. Once I settled the family business, I got a job and started playing hockey again, but the new job didn't give me enough time to play hockey as I had in New York. But I found out that if I started refereeing, I could pick my spots, stay with my job, and make a living at hockey and regular employment with the Sun Life Insurance Company. Meanwhile, my hockey buddy, goalie Riley Hern, fixed me up with his wife's girlfriend (Victoria) and we got married in 1913."

How did marriage influence your officiating career?

"In order to make a decent living for our family, I got a tip that the National Hockey Association, predecessor to the NHL, needed referees. The NHA was a pro league run by Frank Calder, (who) eventually become the first NHL president. A sportswriter at the Toronto Star newspaper saw me work said to Calder, 'Why don't you give Smeaton a chance?'"