“Growing up, he never really wanted me to play like him,” Marchment said. “You know, he was an in-your-face kind of guy. And growing up, I was always that small guy. So, I’d never really played that kind of game. I only adopted it once I got to pro.”

In fact, Marchment said his father, who died at age 53 of a heart attack while in Montreal for the July 2022 NHL Draft as a San Jose Sharks scout, never even pushed him towards hockey.

“For him, it was all about me just having fun and enjoying the day and being a good person,” he said. “Those are the things he wanted me to have and to work for.”

Marchment’s dad kept tabs on his pro progress but was often traveling for his scouting duties. Instead, it was often Marchment and Underhill alone together working on his skating for an hour every other day that first year.

“It was basically a year without playing in any games,” said Marchment, who appeared in three Marlies contests all season. “Obviously, I wouldn’t be here without Barb, but also because of Kyle (Dubas). He really believed in me and crafted this whole plan to get me ready.”

Beyond skating and skills work, Marchment also bulked up with team conditioning coaches so his strength finally matched his size. By his second pro season, the Marlies loaned him to a lower-level ECHL team in Orlando, Florida, where he appeared in only home games and scored 14 goals in 35 contests. He also learned to throw his newfound weight around enough that the AHL squad called him up for nine games.

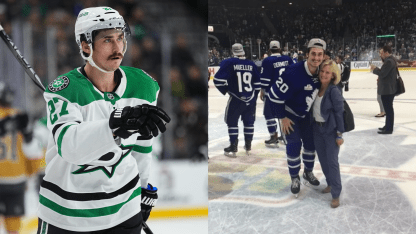

Marchment and Marlies’ coach Sheldon Keefe, now coaching the New Jersey Devils, initially clashed over his lack of playing time. But mutual respect grew and by the following season, Marchment got into 44 games as the Marlies won their first ever Calder Cup AHL championship. Underhill was out on the ice celebrating with him as he hoisted the title trophy.

That title season, in which Marchment scored 11 goals while adding six more in 20 playoff games, seemed to indicate an NHL future loomed. But then, Marchment suffered a shoulder injury the following season that again limited him to only 44 AHL games.

Still, he scored 13 goals and added four more in 13 playoff contests. An NHL opportunity again beckoned the following fall of 2019 in Maple Leafs training camp. But once again, Marchment blew out his shoulder.

Underhill was by his side throughout the rehabilitation.

“This kid just had one injury after another,” she said. “So, he went through a lot of adversity during his time with the Leafs. I mean, it was one shoulder and then I think it was the other shoulder. It was just one thing after another.”

Underhill feels they truly bonded during those rehab sessions.

“I remember a few times when it was just really, really tough,” she said. “But he battled through.”

Marchment admits he questioned whether an NHL career would ever happen.

“My first three years as a pro I had three surgeries,” Marchment said. “So, it’s never easy to come back from that. As much as I thought I was building and ready to start playing in the NHL, those injuries kept me back.”

Still, in the months after his training camp injury, Marchment worked his way back into the Marlies lineup. And then, with the parent Maple Leafs reeling from a slew of injuries to forwards, Marchment finally got his NHL call on Jan. 1, 2020 and debuted the next night in Winnipeg.

He’d log one assist in four games. Then, just as abruptly, he was traded to Florida six weeks later.

Marchment as a pending restricted free agent had been introduced to the business realities of pro hockey. His Leafs, after all, were loaded with some of the NHL’s best forwards and even their lengthy patience and investment in Marchment wasn’t enough to keep him.

Just under two years after the trade, Marchment set a Panthers franchise record with six points in one game, scoring twice and adding four assists as Florida took down Columbus. One month after that, he logged his first career hat-trick in a win over Minnesota as part of an 18-goal season achieved in only 54 games.

The blossoming power forward, playing on a line with Sam Reinhart and Anton Lundell and showing little fear as he plowed toward opposing nets, had made a stellar case for himself heading toward unrestricted free agency.

Marchment’s father got to witness it all.

“He’s got a lot more skill than I had,” he once told the Sporting News. “He doesn’t drop the gloves or whatever, but he’s got compete in his game and he’s a big boy.”

While Marchment hasn’t fought nearly as often as his dad, his increasingly aggressive play in recent years has indeed forced him to answer the occasional bell with his fists. His first NHL bout came against Tampa Bay Lightning heavyweight Zach Bogosian in 2021 and he’s since had at least seven more fights.

But despite Marchment’s rising prominence and reputation for toughness, the talent-laden Panthers -- building a team that would win a Presidents Trophy that 2021-22 season and then make three consecutive Stanley Cup Finals -- decided they could not afford to keep him.

The Stars, seeing Marchment’s talent potential Florida didn’t have room for, quickly pounced with a four-year, $18 million contract. Marchment signed the deal that vaulted him to new career heights just six days after his father’s untimely death.

The rest is history. Marchment came into his own his first season in Dallas, especially during the 2023 playoffs in which he scored four goals – including two plus an assist against the Kraken in a second round series that went the full seven games.

Last season, he registered a second straight 22-goal campaign despite missing two months when teammate Evgenii Dadonov fired a late December shot that deflected off his face near the net front – shattering his jaw and several other facial bones he had to surgically repair. “I couldn’t eat any solid food for two months,” said Marchment, who nonetheless returned and helped Dallas reach a third consecutive Western Conference Final.

Beyond his physical presence and toughness, his 59 playoff games in six seasons with Florida and Dallas caught the eye of Kraken general manager Jason Botterill. Giving up a third-round pick in 2026 and a fourth rounder this past summer for Marchment seemed a no-brainer.

“I think his strength fits very well with what our team needs,” Botterill said. “You look at his forecheck pressure. You look at his ability to get to the net and his size there. I think that’s something our group is looking for and it compliments our players very well.”

But Botterill also feels that -- beyond “X’s and O’s” – Marchment is a player he wants the team’s identity shaped around.

“His story is very similar to what we’re trying to create here,” Botterill said. “Talk about player development. You look at this guy continually working at his game to get to the National Hockey League. And then you go from just a marginal player to a guy that’s played on teams that got to the conference final and was playing a big role.

“So, he’s continued to evolve as a player. And to me, that’s the story. That’s what we are trying to accomplish here.”

For Marchment, it’s a story still unfolding. In September, he and his wife, Lexy, had their first child, Banks Bryan Marchment, a boy whose middle name honors the Kraken forward’s father. And now, Marchment is furthering his own career with expectations for success far greater than anyone ever really imagined possible.

“There are ups and downs,” Marchment said. “And that’s another thing my dad always preached to me. You’re never going to be riding a high for a full season. There’re going to be ups and downs and you’ve just got to enjoy every day.”

And for Underhill, who found the properly fitting skates that got Marchment’s pro journey started, this next chapter will be one worth watching. After all, he’s already proven her initial forecasts wrong by putting in the work needed to recast any expectations of him.

“It is a big process and there has to be a massive commitment to it,” Underhill said. “And they have to believe in it. If they don’t believe in it, then no matter what they’re not going to improve.”

Words the strong-starting Kraken hope they can keep extending beyond the individual to the overall team itself.